- DHS proposes a budget cut for the body-worn camera program, reducing staff from 22 down to 3.

- Funding would plummet from $20.5 million to $5.5 million, raising significant oversight and transparency concerns.

- The cuts occur alongside a surge in ICE enforcement activity and record-breaking detention numbers in 2026.

As ICE faces a surge in arrests, removals, and detainee populations, the administration proposes dramatic budget cuts to the body-worn camera program, raising questions about accountability, evidentiary reliability, and due process. Those questions get sharper when enforcement activity rises fast. More encounters mean more complaints, more contested accounts, and more court fights over what happened.

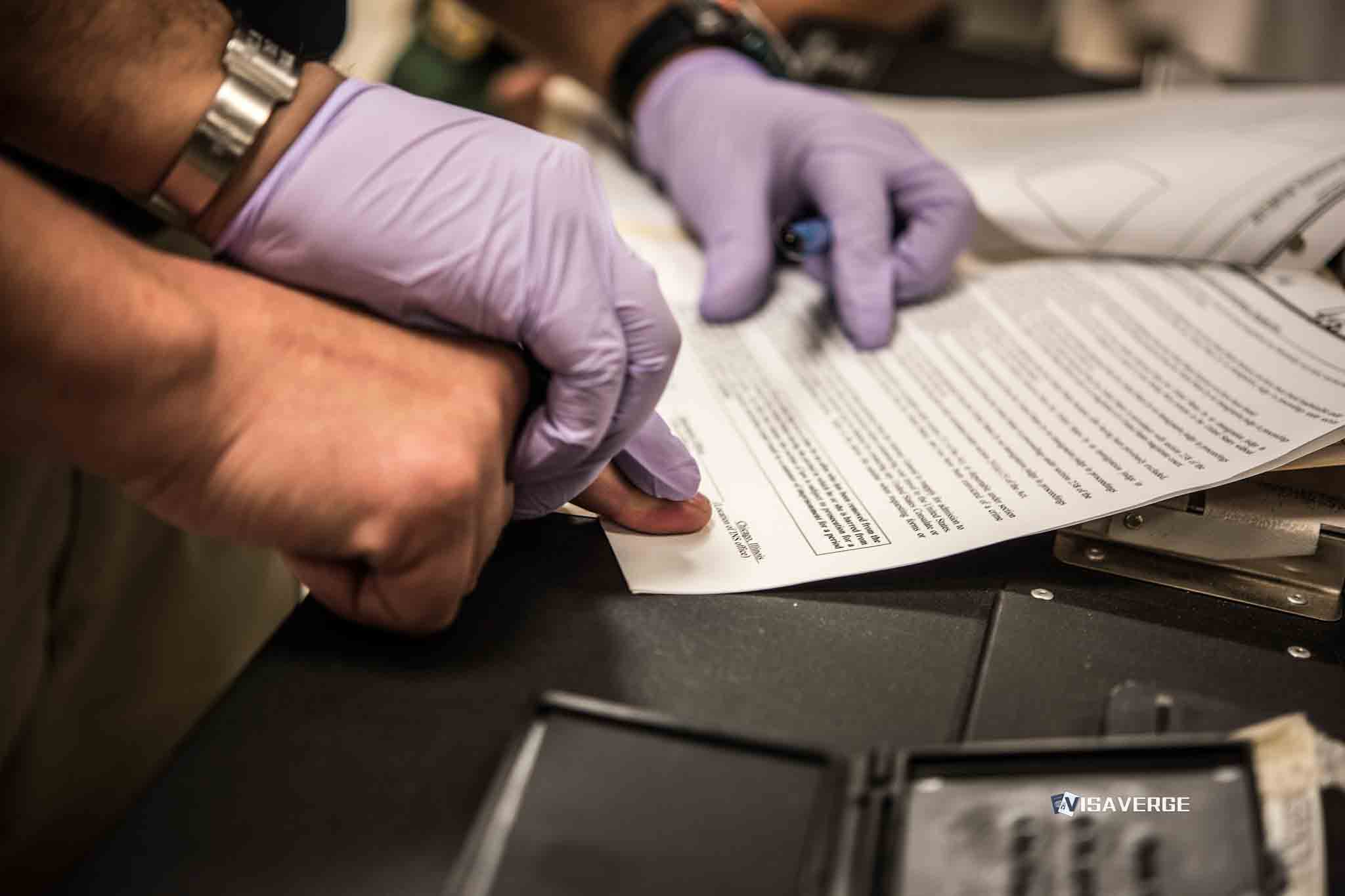

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) body-worn cameras (BWCs) are small cameras worn by officers during enforcement activity. The program is meant to create a time-stamped record of encounters that can serve four common functions: documentation, accountability, evidence, and training.

Think of BWCs like a receipt for a law-enforcement interaction. They do not settle every dispute, but they often narrow what is arguable.

A budget cut does not just mean “fewer cameras.” In practice, reductions can slow deployment, limit replacements, delay repairs, and strain video storage and retrieval. Compliance monitoring can also slip, along with auditing, training, and follow-up on activation rules.

DHS frames the proposed reduction as a tradeoff: money and staff, the argument goes, should shift toward “frontline operations.” Oversight programs often feel that squeeze first because their value shows up later, usually during investigations, court review, or public controversy.

Official statements and key actors

Be cautious about attribution: distinguish between DHS budget justification language, OMB framing, and internal memos when assessing credibility.

DHS budget documents typically read like a priority list. They often justify reductions by pointing to performance measures, shifting mission needs, or administrative burden.

In the DHS Budget Justification (January 2026), DHS proposes shrinking the ICE BWC program from 22 staff to 3, and dropping funding from $20.5 million to $5.5 million. The stated goal is “sustaining” the existing fleet while devoting more resources to “frontline operations.”

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) coordinates the White House budget message and negotiates with agencies. OMB’s statements are usually high level, focused on what the administration supports or opposes.

On January 23, 2026, an OMB official described mandates for body cameras as among “many unserious poison pill demands” from congressional Democrats in the budget bill. That phrasing signals policy posture more than operational detail.

Public messaging can diverge from what field activity looks like. Tricia McLaughlin, a DHS assistant secretary, defended the enforcement surge on January 20, 2026, saying ICE was “unleashed” to target “the worst of the worst” and that “70% of ICE arrests are of criminal illegal aliens who have been convicted or charged with a crime in the U.S.”

Separate debates about transparency do not hinge on that claim alone; they hinge on what can be proven when accounts conflict. Marcos Charles, an ICE official, added an example of credibility testing in real time. At a Minneapolis news conference on January 22, 2026, he said, “We don’t break into anybody’s home,” amid reports of forced entries in the region.

When statements and lived experience clash, video records often decide whether the dispute ends quickly or grows.

Key facts and statistics (as of January 2026)

Volume changes everything. When enforcement ramps up, the number of contested encounters usually rises too. More stops and arrests can mean more allegations of excessive force, more claims of mistaken identity, and more disagreements about consent and entry.

DHS reports a record-breaking year with 670,000 removals and 2 million self-deportations. ICE also expanded fast, hiring 12,000 new officers and bringing the 22,000 ICE workforce to a new level. Detention pressure increased as well, with 73,000 detainees reported in January 2026.

Camera coverage matters in that context. As of June 2025, ICE had 4,400 ICE cameras for a workforce that later grew. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), by comparison, had 13,400 CBP cameras for 45,000 officers. That cross-agency comparison is not a scorecard but a way to grasp scale and the gap between procurement and full coverage.

This section originally included a tabular comparison of cameras and staffing between ICE and CBP. Interactive tools will present the structured comparison; below are the core data points to track:

- ICE: 22,000 workforce; 4,400 ICE cameras. Proposed staffing change for the ICE BWC program: 22 → 3.

- CBP: 45,000 officers; 13,400 CBP cameras. (Staffing details not specified in the source table.)

- Interpretation: workforce growth outpaced camera count; the proposed cut is framed as an attempt to “sustain” the existing fleet rather than expand coverage.

Transparency vs. enforcement: context and use-of-force concerns

Be cautious about attribution: distinguish between DHS budget justification language, OMB framing, and internal memos when assessing credibility.

BWCs sit at the crossroads of transparency and enforcement. Supporters argue they help verify officer conduct, deter misconduct, and speed complaint review, while critics point to privacy risks, administrative burden, and the danger of releasing sensitive footage.

Both sets of concerns grow when enforcement intensifies. In use-of-force reviews, BWCs can clarify timing, distance, and verbal commands. In complaint investigations, they can reduce “he said, she said.”

In court, BWCs can become a central exhibit. That includes immigration-related proceedings and related criminal cases, where factual disputes sometimes spill over into suppression fights or credibility disputes.

Failure points are common: cameras may not be activated, footage may be lost or overwritten, or recordings might be stored under the wrong case identifier. Chain of custody can be challenged if access logs are weak, and delayed disclosure can trigger court sanctions or raise doubts about reliability.

Budget reductions can amplify each weak link. The FY2026 proposal cuts funding from $20.5 million to $5.5 million and shrinks staff from 22 to 3. Fewer staff can mean fewer audits, slower retrieval, and less training—quiet problems until a high-profile event hits.

Congressional attention often spikes after such events. When it does, the question is not only “Did ICE have cameras?” but also “Did the program reliably capture, retain, and disclose the relevant footage?”

Impact on individuals and civil rights considerations

For individuals facing removal, video can be the difference between a dispute that resolves and one that drags on. A recording may support a noncitizen’s account of what was said, whether consent was given, or whether force was used; it may also support the government’s account.

Reduced BWC coverage can affect evidentiary disputes in removal proceedings and related cases. When footage is missing or delivered late, lawyers may argue over credibility rather than facts. Motions may focus on reliability, spoliation, or disclosure timing.

Detention oversight adds another layer. ICE detention facilities are separate from street encounters, yet the accountability story connects. A reported 36% decline in detention facility inspection reports in 2025, combined with fewer recorded field encounters, can leave fewer official records to check claims against.

Vulnerable groups may feel the gaps most. DHS reports a 2,500% surge in non-criminal detainees arrested between Jan 2025 and Jan 2026. Mixed-status families can also face higher stakes in fast-moving encounters, where later disputes turn on whether an officer’s account is the only record.

Notable incidents, memos, and parity with policy

January 2026 brought a flashpoint in Minneapolis when an ICE officer fatally shot Renee Good, a U.S. citizen, in her vehicle. Witnesses and local police accounts conflicted with initial DHS claims that she “rammed” officers. In cases like this, BWCs can act like an instant referee; without them, competing narratives can harden.

An internal memo reportedly signed by Acting ICE Director Todd M. Lyons in May 2025 authorized officers to use “necessary and reasonable force” to enter private homes without judicial warrants, using Form I-205 administrative warrants instead. Debates over entry authority tend to become disputes over what officers said, what residents understood, and what consent looked like.

Video documentation can matter even when legality turns on fine distinctions. Parity arguments sometimes ask why one DHS component has broader camera coverage than another. That argument does not prove misconduct but frames expectations about documentation when federal officers use force or enter private spaces.

Legislative context and funding developments

Congress controls appropriations and can set conditions. Funding alone does not always equal required deployment: a bill can provide money without mandating universal use. Agencies may retain discretion through policy, exceptions, or phased rollouts.

House appropriators proposed $20 million for DHS body cameras in January 2026. The bill did not include a mandate for their use. That split—money without a requirement—matters because it can leave open questions about who must wear cameras, when activation is required, and what exceptions apply.

Oversight levers often appear in report language and conditions. Congress can request audits by inspectors general, ask the Government Accountability Office to evaluate compliance, require reporting on activation and retention, or tie funding to measurable deployment targets. Retention and access rules can also become a battleground, since footage has both privacy risks and evidentiary value.

Callout 1 (action): What to track in the budget cycle

– Committee reports that explain why funding rises or falls

– Continuing resolutions that may freeze programs at prior levels

– Final appropriations language that can add conditions tied to body-worn cameras

Official sources and verification

Verification starts with matching the claim to the right document type. Budget numbers belong in budget books, not press releases. Press statements can show messaging and priorities, but they rarely prove program staffing or procurement details.

Internal memos can show operational guidance, yet they may not reflect final policy or may change quickly. For the BWC cut, the most authoritative place to confirm staffing and line-item changes is the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) budget justification for FY2026. Check the publication date, the fiscal year label, and whether figures refer to ICE program management or total equipment costs.

Save a PDF copy, write down page numbers, and keep notes on definitions. Small wording changes can alter meaning. For public statements, use official DHS and ICE newsroom pages. For related immigration process context, USCIS can help readers confirm broader DHS communications channels and publication timestamps, even though USCIS is not the budget decision-maker for ICE BWCs.

Readers can check USCIS newsroom updates at uscis.gov and cross-reference dates and agency authorship to avoid mixing agencies. When you find a discrepancy, document it like a court citation: capture the title, date, and page number. Then compare apples to apples: FY2026 request vs. prior enacted levels, ICE-only vs. DHS-wide totals, and staffing vs. procurement.

This article discusses budget and civil-rights implications of law-enforcement technology and is subject to legal considerations. Consult primary sources for verification.