(GUANTÁNAMO BAY, CUBA) A federal judge in Washington has ruled that former President Donald Trump exceeded his authority by sending immigrants to Guantánamo Bay without basic legal protections, a 2025 decision that strikes at the heart of presidential power over deportations.

U.S. District Judge James Boasberg found that the administration’s secret transfers to the offshore naval base, and onward to countries such as El Salvador and South Sudan, violated the Due Process Clause of the Constitution because detainees were given no notice and no chance to be heard before removal. He issued a temporary restraining order on March 15, 2025, halting further deportation flights and directing officials to return people who had already been forced onto planes.

What the court found and immediate effects

Court filings described scenes of migrants — and even some U.S. citizens mistakenly detained — taken from U.S. immigration jails with no warning, denied access to lawyers, and placed on military aircraft bound for Guantánamo. Boasberg called the conduct unlawful and said the president could not “erase constitutional protections by changing the zip code of deportation.”

Despite the order, lawyers told the court that the Trump administration proceeded with several flights, including at least one in which people were already in the air when the ruling came down.

According to case records:

– Some passengers were diverted to Guantánamo Bay and held in hastily converted barracks at the U.S. naval base that once housed terrorism suspects.

– Others were rerouted directly to receiving countries that had not been notified in advance.

Government rationale and legal arguments

The administration argued it was acting under the Alien Enemies Act, a little‑used 1798 law whose text appears on the U.S. Code website. That statute allows detention and removal of nationals of hostile states during wartime. Officials also cited broad provisions of the Immigration and Nationality Act.

Government lawyers insisted that people sent to the Caribbean outpost had no constitutional rights because they were not on U.S. soil and were considered “alien enemies” under the statute.

Supreme Court involvement and limits on review

The Supreme Court stepped in after the Justice Department asked it to vacate Boasberg’s ruling. In a 2025 decision the justices sided partly with the administration, allowing deportations tied to the Alien Enemies Act to continue while insisting that detainees could still file habeas corpus petitions in U.S. federal courts.

Key points from the high court’s action:

– The Court wiped away the lower court’s temporary restraining order.

– It accepted that the Due Process Clause applied and that what had already happened breached “fundamental fairness.”

– The justices limited federal judges to reviewing individual habeas challenges to detention at Guantánamo and to removal orders, rather than permitting broader lawsuits over policy.

“Shuttled from Guantánamo Bay to El Salvador and South Sudan as if judicial orders were optional suggestions.”

— Justice Sonia Sotomayor (separate opinion criticizing the administration)

Justice Sotomayor sharply criticized the Trump administration for what she described as open defiance of court authority.

Human impact and legal consequences for detainees

Advocates said some transferred people had pending immigration cases inside the United States and were removed before they could present evidence of fear of persecution or seek protection under U.S. asylum laws.

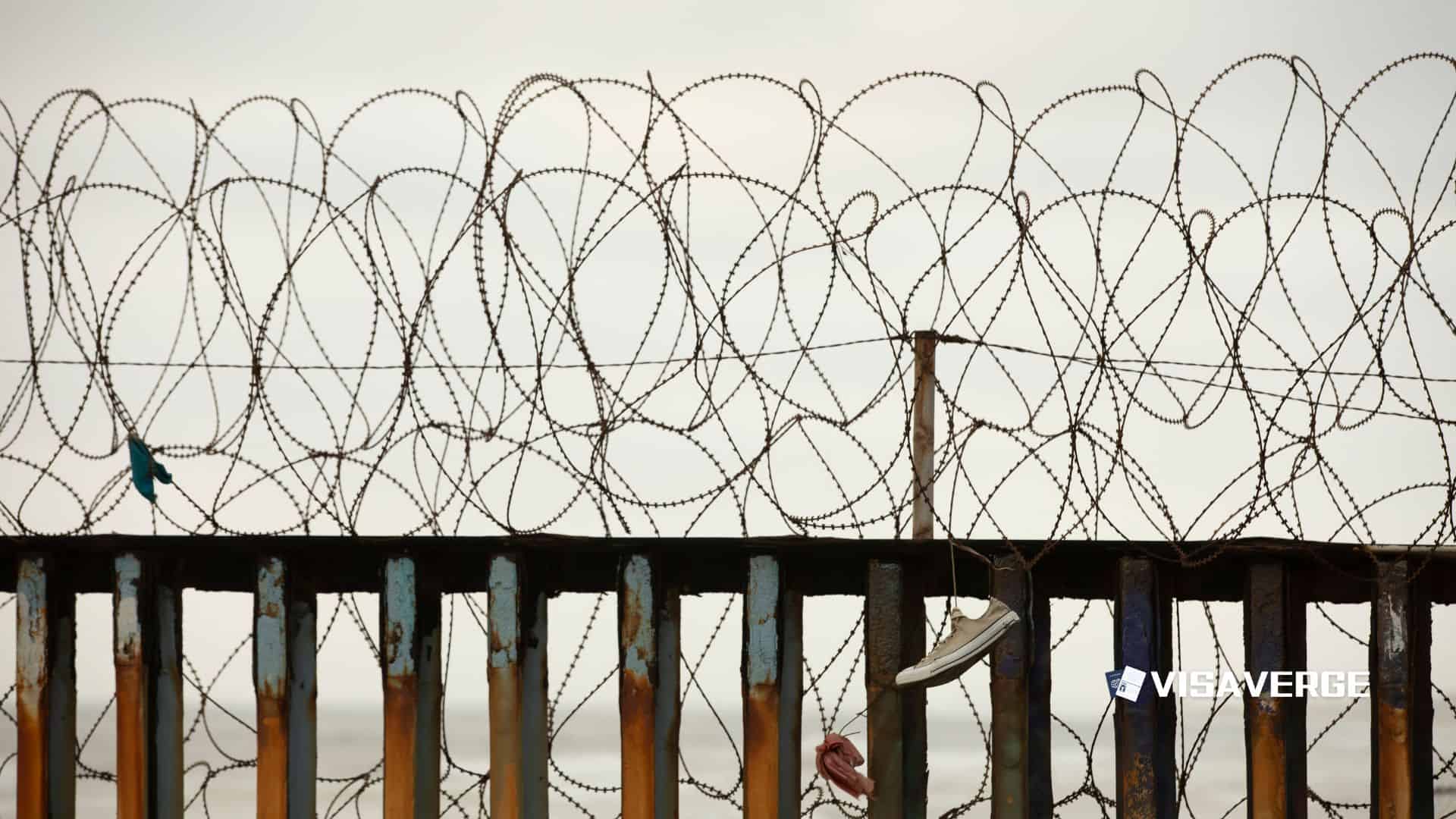

Immigration lawyers compared the policy to “offshore dumping” of migrants, arguing it echoed earlier efforts to keep asylum seekers beyond the reach of courts but went further by choosing Guantánamo, a place associated with terrorism prosecutions and contested legal rights.

Families described frantic attempts to track loved ones moved through multiple facilities. Some only learned weeks later that a husband, sister, or teenage son had been taken first to Guantánamo Bay and then sent on to Central America.

Even with habeas access restored, lawyers say:

– Bringing cases from such a remote and restricted base is slow and costly.

– Many detainees lack documents or communication tools needed to prepare claims while held under tight security.

Operational and financial strain

Defense and Homeland Security officials struggled with the fallout, according to memos cited in court. They attempted to adapt facilities originally built for hundreds of terrorism suspects into a fast‑moving holding center for immigration detainees.

Operations carried a staggering price tag. Government estimates put daily costs at roughly $100,000 per detainee, far higher than holding people in U.S. detention centers on the mainland.

A simple table summarizes the cost contrast:

| Item | Estimate |

|---|---|

| Daily cost per detainee at Guantánamo (government estimate) | $100,000 |

| Typical mainland detention center cost (comparatively) | Much lower (not specified) |

Chartered flights and special security protocols strained budgets and staff already under pressure from record immigration caseloads inside the United States.

Legal, political, and scholarly reactions

Civil liberties groups pointed to the ruling as a reminder that the Constitution follows the flag, arguing that when U.S. officials control a person’s fate at a U.S. base, the Due Process Clause cannot simply be turned off by citing the Alien Enemies Act or similar statutes.

Government officials say the Supreme Court’s decision confirmed that Congress gave the president broad power in emergencies and that habeas review is an adequate safeguard because detainees can still ask a judge to order release or block transfer to a dangerous country.

Legal scholars are divided on whether future administrations will try to use the Alien Enemies Act again in immigration cases. Many, however, believe the fierce reaction to the Guantánamo transfers — including Boasberg’s rebuke and Sotomayor’s warning — will make repeat use politically risky.

Members of Congress are also split:

– Some call for clearer limits on using offshore facilities in immigration enforcement.

– Others warn that tying the president’s hands too tightly could weaken the country’s ability to respond quickly in a national security crisis.

Key takeaways

- The district court found the transfers violated due process and issued a temporary restraining order on March 15, 2025.

- The Supreme Court allowed Alien Enemies Act–linked deportations to continue but preserved habeas corpus review for detainees.

- The policy had severe human, legal, and financial consequences, and provoked strong criticism from judges, advocates, and some lawmakers.

For now, Guantánamo remains a stark symbol of how immigration control, war powers, and constitutional rights collide in practice.

A federal judge ruled that secret transfers of migrants to Guantánamo Bay without notice or hearings violated the Due Process Clause, issuing a temporary restraining order. The Supreme Court partly reversed, permitting deportations under the Alien Enemies Act but preserving detainees’ habeas corpus rights. The policy caused serious human and financial costs, including estimated daily expenses of $100,000 per detainee and operational strain, while provoking widespread legal and political criticism.