- Virginia and Washington are facing federal scrutiny after limiting local cooperation with ICE enforcement operations.

- DHS is currently gathering data on federal funding sent to jurisdictions that restrict civil immigration assistance.

- Reduced jail cooperation may shift arrests into public-facing community settings like homes or workplaces.

(VIRGINIA) — A growing state–federal dispute over immigration cooperation is changing how removals may be carried out in Virginia and other “non-cooperative” jurisdictions, and it matters most to immigrants with prior ICE contact, people in removal proceedings, and families trying to plan safely around arrests that may shift from jails to the community.

At a practical level, “state–federal immigration cooperation” usually means whether state and local agencies will help federal officials with civil immigration enforcement. That can include honoring ICE detainers, sharing release-date information from jails, participating in task forces, or providing staff time and facilities support.

When a state limits those forms of assistance, ICE can still enforce federal law, but it may have fewer “handoffs” from local custody. That often pushes more enforcement activity into public-facing settings.

Virginia is now at the center of that dynamic after a leadership change in Richmond and a reported reversal of prior cooperation-oriented directives. Readers should separate what is confirmed (public executive actions and official statements) from what is unconfirmed (leaked memos and rumors about tactics).

The operational impact will depend on the exact wording of state directives, federal deployment decisions, and how local agencies implement day-to-day procedures.

Warning: A state’s refusal to assist with civil immigration enforcement does not stop federal enforcement. It may change where arrests happen and how visible they are.

1) Who is driving the dispute, and what statements mean (and don’t mean)

The most direct recent signal came Friday, January 23, 2026, when White House “Border Czar” Thomas Homan said prospects for cooperation with Virginia and Washington “doesn’t look good,” in comments tied to Virginia Governor Abigail Spanberger’s early executive actions. As described, Homan is speaking as a senior administration messenger on enforcement priorities.

Statements like this can indicate posture, urgency, and intended resource allocation. They are not, by themselves, an enforceable legal directive.

President Donald Trump also publicly criticized non-cooperation, describing it as a “bad signal.” Presidential comments can shape agency priorities and tone. But the mechanics of enforcement still run through DHS components and existing statutes and regulations.

More concretely, DHS reportedly issued internal direction to compile information about federal funding going to “sanctuary” jurisdictions, naming Virginia, Washington State, and the District of Columbia. The memo language described in the source is important because it frames the action as data collection, not an immediate funding cutoff.

2) The step-by-step process: how a cooperation dispute turns into real enforcement changes

What follows is the typical process by which a state-level posture shift can translate into federal operational changes. Each step has decision points where outcomes may vary by county, by agency, and by court jurisdiction.

Step 1 — Virginia issues (or rescinds) executive direction on civil immigration support

What it accomplishes: Sets rules for when state resources can assist ICE with civil immigration enforcement.

- Key documents: Virginia executive order(s) and any rescission notice(s)

- Key documents: Agency guidance to state police, corrections, and administrative agencies

Decision points:

- Whether the directive limits only affirmative assistance (staff time, facilities, transport)

- Whether it restricts communication of release dates

- Whether it covers state agencies only, or also conditions state funding for localities

Common mistake: Assuming “sanctuary” is a single legal status. Policies vary widely and can be partial.

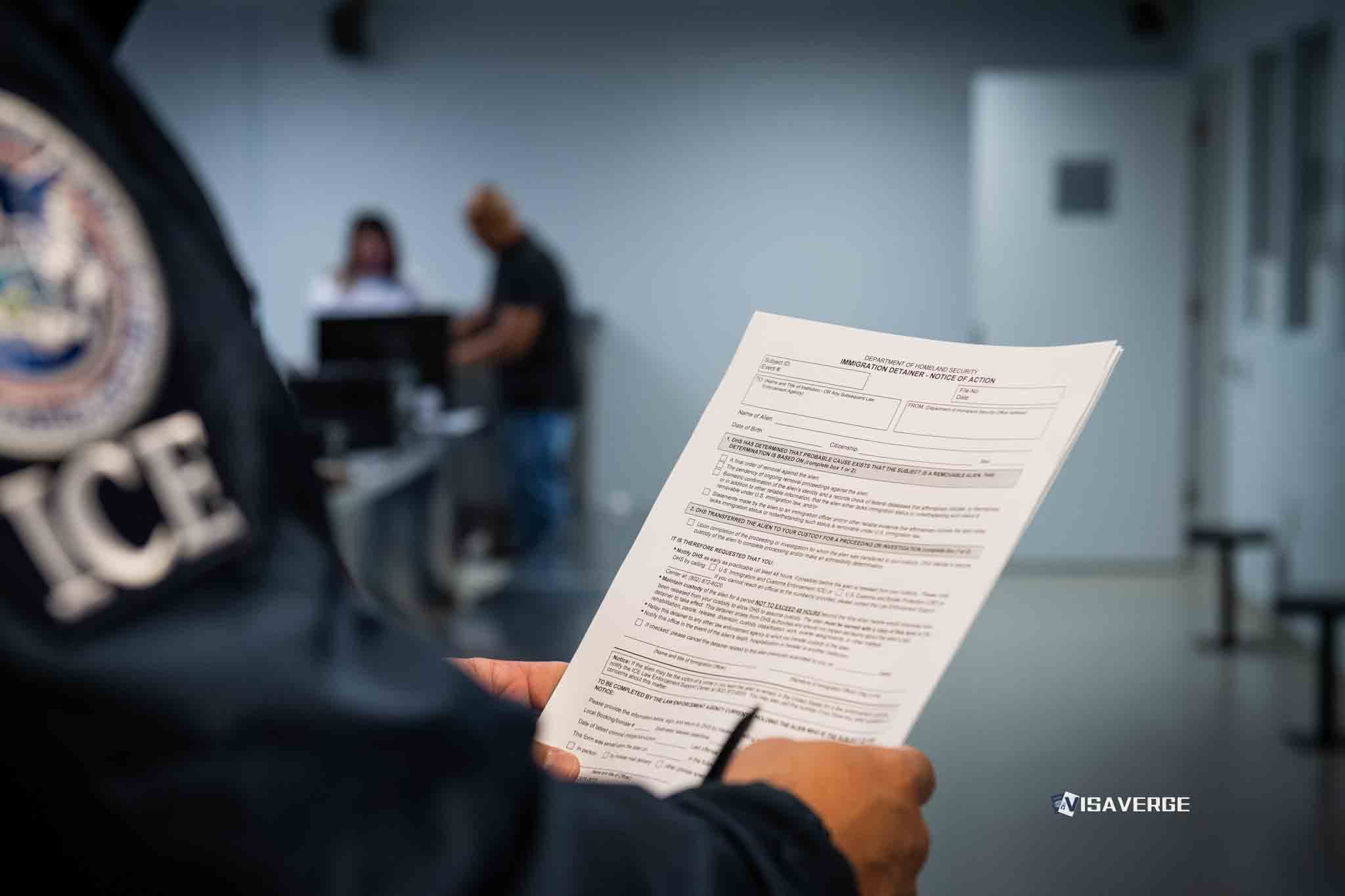

Step 2 — Local jails decide how to handle ICE detainers and notice requests

What it accomplishes: Determines whether ICE can make arrests at the point of local release.

- Key documents you may see: ICE detainer forms (commonly issued on Form I-247 variants)

- Key documents you may see: Jail release paperwork and “notification” logs

- Key documents you may see: Local policy memos on compliance

Relevant law (high-level):

- Detainers are requests. They are not criminal warrants.

- Local authority to hold someone longer can raise state-law and constitutional issues.

Timeline: This can change fast after a new order, sometimes within days. Implementation may lag for weeks.

If detainer practices change, ICE arrests may shift from “jail pickup” to at-large arrests. That can affect family planning and safety.

Step 3 — ICE adjusts enforcement planning when custody transfers drop

What it accomplishes: Reallocates field teams and changes arrest locations.

Operational changes that often follow:

- More at-large arrests near homes, workplaces, or during travel

- More surveillance and “knock-and-talk” encounters

- More emphasis on locating people with prior final orders

Decision points:

- Whether ICE prioritizes people with criminal histories or broad categories

- Whether federal leadership deploys additional personnel to Virginia or Washington

Step 4 — Individuals encounter one of three main immigration “tracks”

What it accomplishes: Determines whether a person is processed through detention, immigration court, or direct removal based on posture and prior history.

- Track A: Removal proceedings in immigration court (EOIR)

- Documents: Notice to Appear (NTA); custody paperwork; hearing notices

- Law: INA § 240 (removal proceedings)

- Timeline: Often months to years, depending on the court docket

- Track B: Reinstatement / prior order enforcement

- Documents: Prior order records; ICE paperwork; sometimes a reasonable fear screening if claimed

- Law: INA § 241(a)(5) (reinstatement) may apply in some cases

- Timeline: Can move quickly, sometimes days or weeks

- Track C: Detention and bond considerations

- Documents: Form I-286 (Notice of Custody Determination) may be issued; hearing request for bond if eligible

- Law: INA § 236 (arrest and detention); bond rules vary by category

- Timeline: Bond hearings can occur quickly, but schedules vary by court

Common mistake: Missing EOIR deadlines after a change in arrest patterns. Always keep your address updated with EOIR and USCIS where required.

If you are in immigration court, you must follow EOIR address-change rules. Missing a hearing can lead to an in absentia order. See 8 C.F.R. § 1003.15(d) and 8 C.F.R. § 1003.18.

Step 5 — DHS “data gathering” on funding occurs (separate from enforcement)

What it accomplishes: Creates an interagency picture of which grants, reimbursements, and programs touch “non-cooperative” jurisdictions.

What it typically includes:

- Grant programs, reimbursement streams, and eligibility terms

- Program participation data and compliance certifications

- Conditions tied to performance metrics or reporting

What it does not automatically mean:

- Immediate termination of funds

- Automatic legal authority to impose new grant conditions

Decision points: Whether DHS attempts new conditions through rulemaking, grant amendments, or enforcement of existing terms; whether states or cities sue, and whether courts enjoin changes.

Timeline and delays: Funding actions often take weeks to months. Litigation can stretch far longer.

3) “Flood the zone” and self-departure incentives: what’s real versus rhetorical

The administration’s described “flood the zone” concept is best read as an operational answer to reduced jail access: more agents, more field activity, and higher visibility in places where custody transfers are limited. Whether that occurs, and at what scale, is a resource and policy choice.

Separately, DHS has highlighted “self-departure” incentives administered through a CBP-linked app. Conceptually, these programs seek to encourage voluntary departure outside contested detention capacity.

Reports describe a recent increase in the “exit bonus,” with a before-and-after change. Readers should treat the exact numbers and dates as something to confirm directly through official DHS postings.

4) A careful note on home entries, warrants, and what people should know

Rumors spread quickly during enforcement surges, especially around whether agents can “enter homes.” As a general rule, entering a home without consent typically requires judicial authorization under the Fourth Amendment.

Immigration enforcement can involve different warrant types, and administrative warrants are not the same as judicial warrants. Fact patterns also vary, including exigent circumstances.

Because reports referenced an internal memo, readers should be cautious about treating secondhand summaries as binding policy. If an encounter occurs, the safest legal course is to stay calm, avoid obstruction, and ask to speak with counsel.

Do not rely on social media summaries about “new rules.” If you have a prior removal order or a pending case, consult an attorney about risk and options.

5) Practical impacts for immigrants and families in Virginia and Washington

If jail transfers to ICE decrease, federal arrests may become more public. Visibility can mean more field operations, more stops outside custody settings, and more attempts to locate people at known addresses.

In non-cooperative jurisdictions, ICE may use workarounds that do not depend on local jail coordination. That can include more surveillance and more effort to execute arrests in the community.

These shifts can also affect court appearances and check-ins. People who previously expected “jail pickup” risk may now face a different pattern: enforcement tied to routine travel, work schedules, or home contacts.

Anyone with prior ICE contact should keep copies of immigration paperwork, track hearing dates, and get individualized advice before making major decisions like travel or job changes.

Attorney assistance is especially important for people with final orders, prior deportations, criminal history, or pending asylum or cancellation claims. Relief options can exist, but eligibility depends on precise facts and jurisdiction.

6) What to watch next in the Virginia–Washington conflict

The “Second Border War” framing is politically potent, but rhetoric can move faster than the underlying legal mechanism. Virginia’s shift is treated as significant because it signals movement from a previously cooperative posture to a more restrictive one, potentially changing the federal enforcement map along the East Coast.

Concrete markers to monitor include: the text of signed orders, implementing guidance to agencies, DHS grant letters, and documented operational changes on the ground. Litigation is also a common next step in sanctuary-funding disputes, and outcomes can vary by circuit.

For verification, rely on official postings from DHS and USCIS, and on ICE program descriptions such as the 287(g) framework, which illustrates one formal route for cooperation.

7) Official sources and a verification checklist

Check official updates around major announcements and before any scheduled check-in or court date. Save copies of NTAs, hearing notices, bond paperwork, and any ICE documents you are given.

If you learn your state issued a new directive, try to locate the signed document and any agency implementation memo, not just a headline.

Official government sources to confirm developments include:

- DHS Newsroom

- USCIS Newsroom

- ICE 287(g)

Resources:

- AILA Lawyer Referral

- Immigration Advocates Network

⚖️ Legal Disclaimer: This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.