(XINJIANG, CHINA) — A pending new york immigration court case involving Xinjiang whistleblower and citizen journalist Guan Heng is drawing unusual attention because it sits at the intersection of asylum law, detention practice, and the government’s ability to attempt third-country removal while an applicant fights deportation to China.

Although there is no new published “Guan Heng precedent” yet, the legal frame is familiar: immigration judges must decide whether a person who fears persecution can obtain protection under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), and whether DHS can lawfully execute removal in a way that complies with statutory and treaty-based limits.

The practical impact for similar cases is immediate. detained asylum seekers with high-profile speech, irregular entry, or alleged foreign-state retaliation should expect aggressive litigation over custody, country of removal, and credibility—and they should plan early for corroborating evidence and expert support.

1) Overview: who Heng Guan is and why this case matters now

Guan Heng (also reported as Heng Guan) is a 38-year-old Chinese citizen journalist and whistleblower whose public profile stems from documenting detention facilities in Xinjiang.

According to accounts provided by counsel and advocates, he secretly recorded video evidence of camp sites and later released a 19-minute video that corroborated reporting on mass detention of Uyghurs.

In plain terms, his U.S. case is about whether he can stay in the united states under asylum-related protections, or whether DHS can remove him—raising the core fear scenario described by supporters as deportation to China, where they say he would face severe punishment due to his reporting.

Procedurally, the case is being watched because it includes: (1) detention while asylum is pending, (2) an attempted plan to send him to a third country rather than China, and (3) congressional and public pressure that appears to have changed DHS’s immediate removal posture.

Readers will find this useful as a guide because it explains the basic immigration-court steps, what the government has publicly said, and what similar applicants can do to protect their cases without assuming any outcome.

A timeline of the key procedural milestones has been reported publicly, including his entry and asylum filing, later ICE detention, the proposed third-country removal concept, the subsequent withdrawal of that concept, and a scheduled immigration-court hearing on January 12, 2026.

2) Official statements and legal posture: what DHS said, what changed, what remains unresolved

DHS has made only limited public statements. One DHS Public Affairs statement, attributed to Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin and dated December 18, 2025, said ICE “encountered” Guan during assistance to the FBI executing a criminal search warrant, and that “all of his claims will be heard before an immigration judge.”

That phrasing matters. It signals DHS expects the immigration court (EOIR) process to adjudicate his protection claims rather than an immediate administrative removal without a hearing.

The most concrete procedural change reported is DHS’s withdrawal of a request to remove Guan to Uganda. Public reporting describes that reversal as occurring after bipartisan congressional pressure, and as being communicated to counsel even without a standalone DHS press release.

It is important not to overread that withdrawal. Withdrawing a third-country plan does not equal a grant of asylum. It also does not mean DHS has conceded the merits.

As of early January 2026, DHS representatives reportedly declined to state whether the agency will support or oppose asylum, citing ongoing proceedings.

In immigration court terms, the posture appears to be: (1) the case remains pending before an immigration judge, (2) the parties will litigate eligibility for relief and, often, custody issues in parallel, and (3) DHS may still pursue removal if the judge denies relief, subject to appeal.

Warning: A withdrawn third-country removal request is not a legal “win” on asylum. It may reduce one immediate risk, but the underlying removal case can continue.

3) Key facts and policy details readers should understand (without legal jargon)

Why whistleblowing matters in asylum law. At a high level, asylum under INA § 208 can be based on persecution tied to a protected ground, including political opinion.

Journalistic activity and exposing state abuse can, in some cases, be framed as political opinion or imputed political opinion. Each case turns on evidence: what the applicant did, how officials reacted, and what would likely happen upon return.

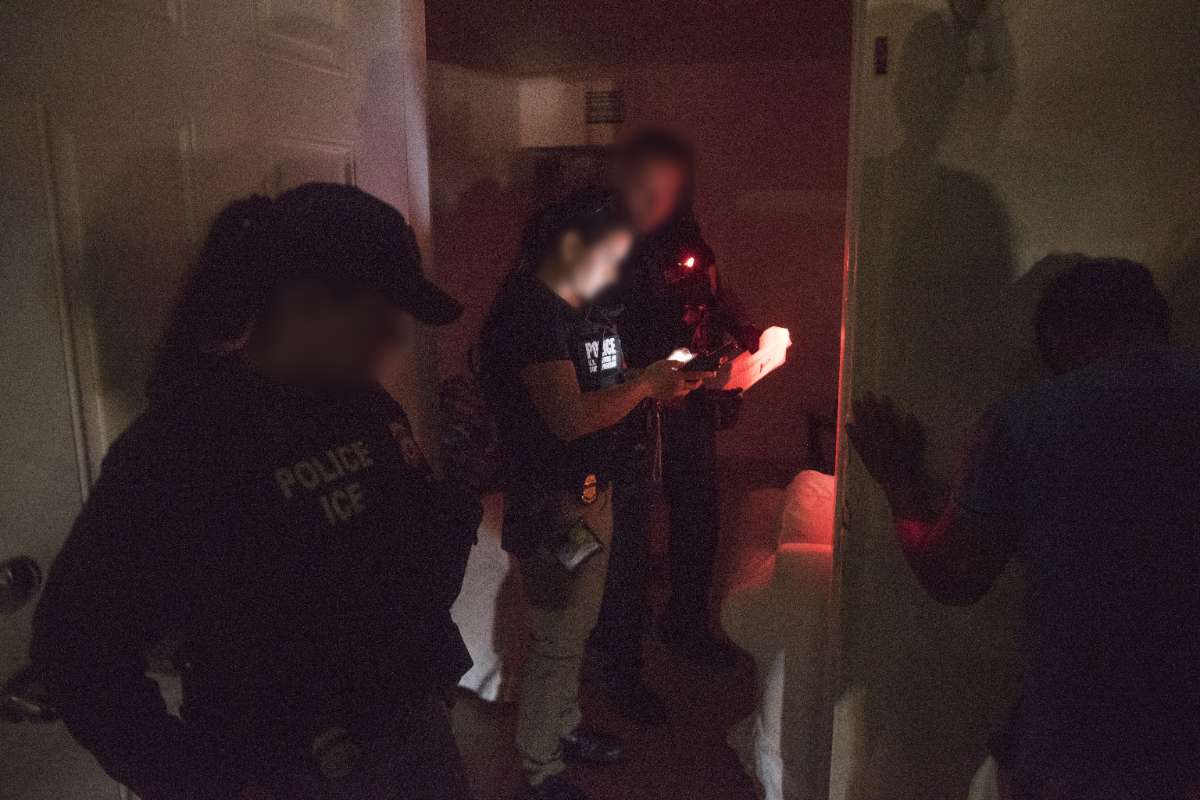

Detention and its practical effects. Guan has reportedly been held at Broome County Jail in Binghamton, New York.

Detention can complicate case preparation. Access to documents, witnesses, and mental health care may be limited, and attorney visits and interpretation resources can be harder to coordinate.

These conditions often become relevant not only to case preparation, but also to custody reviews and bond litigation where available.

What “third-country deportation” usually means. In general terms, DHS may designate a country of removal under INA § 241(b). Litigation sometimes arises when DHS seeks removal to a country other than the person’s country of nationality, or when the third country may transfer the person onward.

Separate from asylum, U.S. law also bars removal to a country where the person is “more likely than not” to face torture under regulations implementing the Convention Against Torture (CAT). See 8 C.F.R. §§ 1208.16–1208.18.

Even when Uganda (or any third country) is not the feared persecutor, applicants may argue that removal there creates a chain-refoulement risk, meaning eventual transfer to the persecuting country. Whether such a theory succeeds depends on evidence and the legal framework in the applicable circuit.

What a scheduled hearing usually signals. A hearing before an immigration judge can cover several things: pleading to the Notice to Appear, scheduling deadlines, custody issues, and eventually an “individual hearing” where asylum and related claims are tried.

Immigration court scheduling varies by location and detention status.

Deadline note: In immigration court, judges often set strict filing deadlines for evidence, witness lists, and briefs. Missing a deadline can result in exhibits being excluded.

4) Context and significance: enforcement priorities, human rights concerns, and transnational repression

Advocates describe a perceived irony: evidence linked to Xinjiang abuses has informed U.S. public condemnation and sanctions, while the same government is enforcing removal against the person who helped document those abuses.

That framing is politically potent, but it does not control the legal standard an immigration judge must apply.

Press freedom and human rights groups, including Reporters Without Borders and the Committee to Protect Journalists, have raised concerns about “transnational repression.” That term is generally used to describe a foreign government’s efforts to threaten, surveil, or coerce dissidents abroad and to punish them if they return.

In asylum litigation, such concerns may become relevant as country conditions evidence, expert testimony, and proof of individualized risk.

Still, immigration judges decide cases based on the record and the legal elements for each form of relief. Advocacy can shape public debate and sometimes influence discretionary decisions, but it does not substitute for corroboration, consistent testimony, and legally sufficient nexus.

5) Impact on individuals and networks: what this case signals for asylum seekers and advocates

For detained applicants, the immediate impact is personal and procedural. Lawyers for Guan have described severe anxiety and panic in custody.

Mental health symptoms can affect memory and testimony, and they often require careful documentation and trauma-informed preparation.

The case also highlights the potential risk to family members abroad. Advocacy group accounts state that relatives were questioned and pressured.

In many asylum cases, harm or threats to family can strengthen the fear narrative, but it can also create hard safety decisions about contact, communications, and evidence gathering.

More broadly, the situation signals that irregular entry—even with a strong political story—may still result in detention and contested litigation. Applicants should expect DHS to examine inconsistencies, travel route details, and document authenticity.

Two core precedents frequently shape these cases:

- Asylum discretion and credibility are heavily record-driven. Even strong country conditions do not replace individualized proof.

- CAT and withholding are separate from asylum. Applicants denied asylum may still pursue withholding of removal under INA § 241(b)(3) or CAT protection if the evidence meets those standards.

On country-conditions proof and corroboration, immigration courts often look to established BIA frameworks. While no single case resolves all issues, Matter of Mogharrabi, 19 I&N Dec. 439 (BIA 1987) remains a commonly cited decision discussing well-founded fear principles.

Later statutes and REAL ID credibility rules can require corroboration when reasonably available. Credibility and corroboration disputes are also highly circuit-dependent.

Warning: High-profile activism can cut both ways. It may support a political opinion claim, but it can also invite intense credibility scrutiny and government rebuttal evidence.

6) Official and primary sources: where readers can verify updates and statements

Because facts and posture can change quickly, readers should rely on dated, official sources:

- DHS Newsroom for formal DHS statements and enforcement updates

- EOIR (Immigration Court) information for court procedures and legal orientation resources: [justice.gov/eoir](https://www.justice.gov/eoir)

- USCIS Newsroom for broader asylum-related policy context (noting that detained court cases are EOIR-driven): [uscis.gov/newsroom](https://www.uscis.gov/newsroom)

- Congressional statements that may reflect oversight or advocacy, including the House Select Committee on the CCP and the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission (verify date stamps and archived versions).

When reading public statements, separate three categories: (1) what DHS has confirmed, (2) what counsel reports as communications from DHS, and (3) what advocacy groups allege about foreign-state conduct. Each category has different evidentiary weight in court.

Practical takeaways for similar cases

- Assume detention will compress timelines. Prepare declarations, translations, and expert outreach early.

- Build a corroboration plan. Preserve original files, metadata where possible, and third-party authentication.

- Address third-country removal risk directly. If DHS raises it, the response may require country-specific evidence and CAT-focused arguments.

- Plan for appeal. EOIR decisions can be appealed to the BIA, and then to the federal circuit court, but deadlines are short and vary by posture.

Given the stakes in cases involving Xinjiang-related whistleblowing and alleged retaliation, consultation with a qualified immigration attorney is not optional in practice; it is the difference between an organized evidentiary record and a patchwork defense.

This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.

Resources:

This report examines the legal case of Guan Heng, a Chinese whistleblower detained in the U.S. while seeking asylum. It covers his journalistic background in Xinjiang, the procedural history of his detention, and the recent withdrawal of a third-country removal plan to Uganda. The content details the legal framework of the Immigration and Nationality Act and the impact of congressional advocacy on DHS enforcement decisions.