(UNITED STATES) The Supreme Court’s decision on December 5, 2025 to hear a direct challenge to President Donald Trump’s executive order ending automatic birthright citizenship marks one of the most closely watched immigration cases in decades, with millions of children and families in the United States 🇺🇸 and abroad waiting for answers. At stake is whether babies born on American soil to undocumented parents or to parents on temporary visas will still be citizens, and whether a president can change that long‑standing rule with a single executive order, EO 14160, that federal courts have so far kept on hold nationwide.

Signed on January 20, 2025, Trump’s order declares that children born in the country after February 19, 2025 are not citizens at birth if neither parent is a U.S. citizen nor a lawful permanent resident. That would exclude children of undocumented immigrants and of parents on student, work, or tourist visas, including F‑1 and H‑1B holders. Lower federal courts in several states quickly blocked the order, ruling that it clashes with the Fourteenth Amendment and more than a century of Supreme Court law on who becomes American at birth. Those rulings keep the administration from letting the policy take effect.

Constitutional core: the Citizenship Clause

At the center of the dispute is the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, adopted after the Civil War to guarantee that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens.”

Since 1898, when the Supreme Court decided United States v. Wong Kim Ark, that language has been read to protect birthright citizenship for almost everyone born on U.S. soil, regardless of whether their parents are citizens, permanent residents, or present without lawful status. One narrow, long‑recognized exception has been children of foreign diplomats.

This case is the first time since EO 14160 was signed that the Supreme Court has agreed to decide the central constitutional question, rather than focusing on temporary injunctions or technical issues. The justices are expected to hear oral arguments in spring 2026, with a ruling likely by early summer 2026.

The outcome will determine whether birthright citizenship remains a dependable promise, or whether children’s status can depend on their parents’ paperwork.

Who would be affected

Under the order, a child born in the United States after February 19, 2025 would no longer be a citizen at birth if both parents lack citizenship or a green card, even if the family has lived in the country for years.

- Affected groups would include:

- Parents on F‑1 student visas

- Parents on H‑1B professional visas

- Parents on tourist visas

- Undocumented parents

Table: Examples of visa categories and potential effect

| Visa / Status | Typical holders | Would child be excluded under EO 14160? |

|---|---|---|

| F‑1 | International students | Yes |

| H‑1B | Skilled professionals | Yes |

| Tourist visas | Short term visitors | Yes |

| Undocumented | No lawful status | Yes |

| Permanent residents (green card) | Lawful permanent residents | No |

| U.S. citizens | Naturalized or birthright citizens | No |

Legal arguments and positions

Supporters of the order argue:

– The Supreme Court should allow a narrower reading of the Fourteenth Amendment.

– They claim Wong Kim Ark went too far and that Congress, not the Constitution alone, should decide which births count.

Opponents argue:

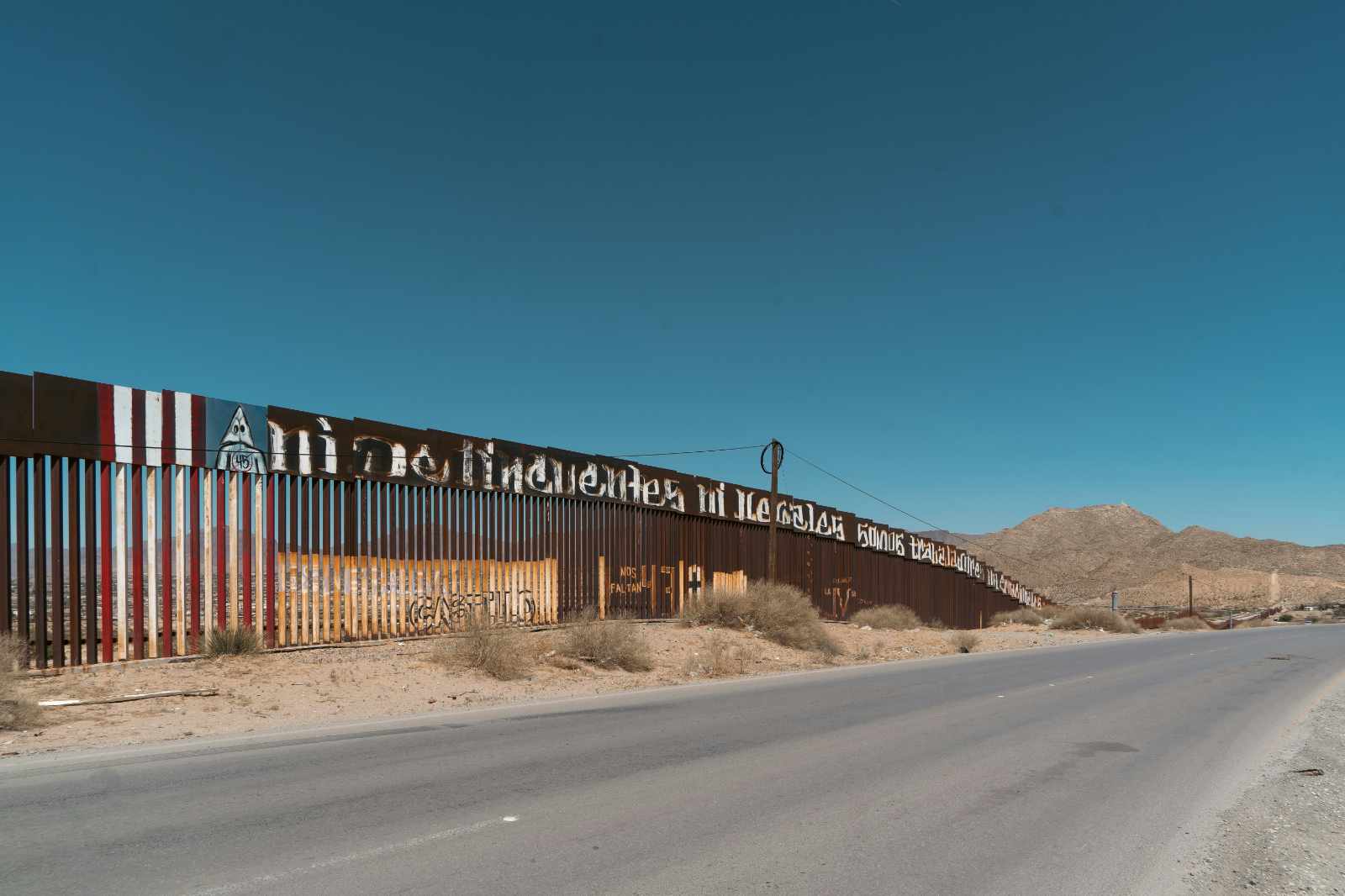

– The order shreds settled law and would create a permanent class of people born here without full national membership.

– Civil rights and immigrant groups warn of racial profiling, constant document checks, and long‑term exclusion.

Notable statements:

Morenike Fajana, senior counsel at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, called the policy “a direct attack on the constitutional promise of equal citizenship.”

Aarti Kohli, executive director of the Asian Law Caucus, warned that tying legal status at birth to parents’ papers will invite racial profiling and constant document checks.

Tianna Mays, legal director of the Democracy Defenders Fund, said she is confident the Court will keep birthright citizenship intact, despite intense political pressure.

Practical consequences for families and communities

For immigrant families already in the country, the case creates a fog of uncertainty around children’s futures. Parents who are undocumented, on temporary visas, or awaiting green cards had long assumed that babies born in U.S. hospitals would be citizens—able to study, work, and vote without extra paperwork. Now, lawyers say, those families must consider the risk that the Supreme Court could uphold the order and strip that expectation away.

According to analysis by VisaVerge.com, many non‑resident Indians and other global professionals are already rethinking where to have children and how to plan careers abroad, given this dispute.

For many in the Indian diaspora, the case changes how they view the United States as a long‑term base. Families who once considered birthright citizenship a safety net during assignments or studies abroad now hear U.S. officials talk about limiting that right.

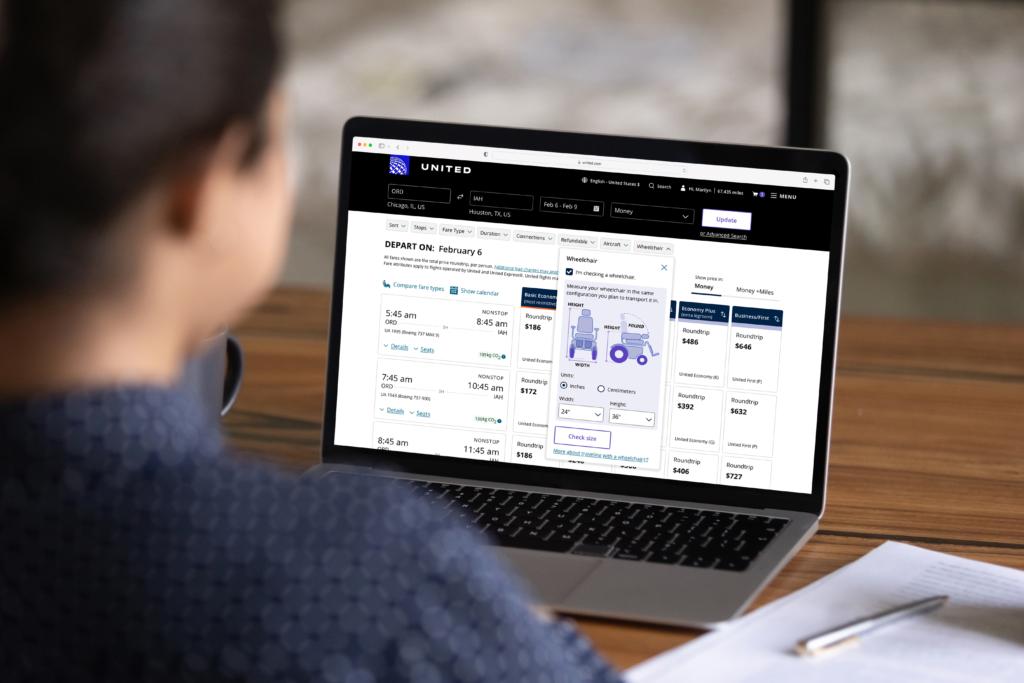

- Some immigration attorneys advise clients to:

- Learn about longer work visas

- Consider eventual naturalization through Form N-400 Application for Naturalization

- Track official guidance on citizenship at USCIS.gov

Global mobility and economic impacts

Beyond legal questions, the pending ruling is already shaping global mobility plans.

- Education consultants report parents in Asia and Latin America asking whether they should still send children to U.S. universities.

- Business groups worry skilled workers on H‑1B visas could feel less rooted if their U.S.‑born children no longer receive automatic citizenship.

- Advocates fear a ripple effect, with future laws or executive actions aimed at:

- Green cards

- Work visas

- Humanitarian protections

They argue uncertainty can push talent toward other destinations.

Presidential power and broader legal stakes

Legal scholars across the spectrum say the case raises a sharp question about presidential power. The Court must decide not only how to read the Fourteenth Amendment, but also whether a president may rewrite a constitutional rule through an executive order rather than through a constitutional amendment or an act of Congress.

So far, lower courts have held that:

– The Citizenship Clause means what it has meant since Wong Kim Ark.

– Only the Supreme Court itself can change that reading, if it chooses to do so.

The justices now confront that question directly.

What to expect procedurally and how people are preparing

- Oral arguments: Spring 2026

- Decision likely: Early summer 2026

- Meanwhile, community groups are holding forums and lawyers are advising parents who are pregnant or planning pregnancies to follow developments closely.

Practical steps families and advocates are taking:

– Collecting birth records, immigration documents, and proof of ties to home countries

– Consulting immigration attorneys about alternatives and contingency plans

– Preparing for potential litigation and administrative challenges that could last years

Immigration lawyers stress that nothing has changed yet for children already recognized as citizens, and that any switch in policy would almost surely trigger years of follow‑up litigation and legislation.

Potential long‑term consequences

If the Court upholds EO 14160:

– The effects may extend beyond babies born after the cut‑off date.

– A ruling that allows narrowing the Citizenship Clause by executive order could encourage future presidents to test other limits on immigrant rights.

– Opponents warn it might inspire state‑level efforts to restrict services for children the federal government no longer treats as citizens.

If the Court strikes down the order:

– It would reaffirm Wong Kim Ark and close the door on similar attempts for now.

– Political debate would likely continue.

Human stories behind the docket

Behind the legal filings are families making difficult choices. Examples include:

– A graduate student from India on an F‑1 visa expecting a baby in 2026, who may face choices such as returning home for the birth.

– Undocumented parents who fled violence or poverty, whose U.S.‑raised children might struggle to prove status anywhere.

Advocates say these private decisions, repeated thousands of times, show how the case reaches far beyond the courthouse into homes across the world.

Competing legal narratives

Trump administration lawyers defending EO 14160 in lower courts have argued that the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction” in the Fourteenth Amendment leaves room to deny automatic citizenship to some children of non‑citizens.

Conservative legal groups supporting the order argue:

– Reconstruction‑era Congress never meant to grant citizenship to children whose parents lacked permanent ties to the nation.

Civil rights organizations reply:

– The Supreme Court already answered those claims in Wong Kim Ark.

– Any retreat now would break faith with generations who relied on the promise that birthplace, not bloodline, defines American citizenship for everyone born here.

Closing note

As the docket moves toward argument, observers note the stakes are enormous. The Court’s reading of birthright citizenship will shape how the world sees the United States as a destination for study, work, and family life. For many global families—especially those with ties to India and other large diasporas—this may be the immigration ruling that defines the decade and influences where future generations choose to build homes.

The Supreme Court will decide whether EO 14160 — signed Jan. 20, 2025 — can strip automatic citizenship from children born after Feb. 19, 2025 to noncitizen or non‑permanent resident parents. Lower courts blocked the order, citing the Fourteenth Amendment and longstanding Wong Kim Ark precedent. Oral arguments are expected in spring 2026, with a likely ruling by early summer. The outcome could affect millions, including families on F‑1, H‑1B, tourist visas, and undocumented parents, and would reshape presidential power over citizenship.