(UNITED STATES) The United States 🇺🇸 will require all H-1B visa seekers and their H-4 dependents to open up their online lives to consular officers from December 15, 2025, in a move that extends social media screening from students and exchange visitors to one of the country’s most important skilled‑worker visa routes. Under the expanded vetting policy, applicants must list all social media profiles they have used in the past five years and make those accounts publicly viewable before their visa interviews.

What the change requires

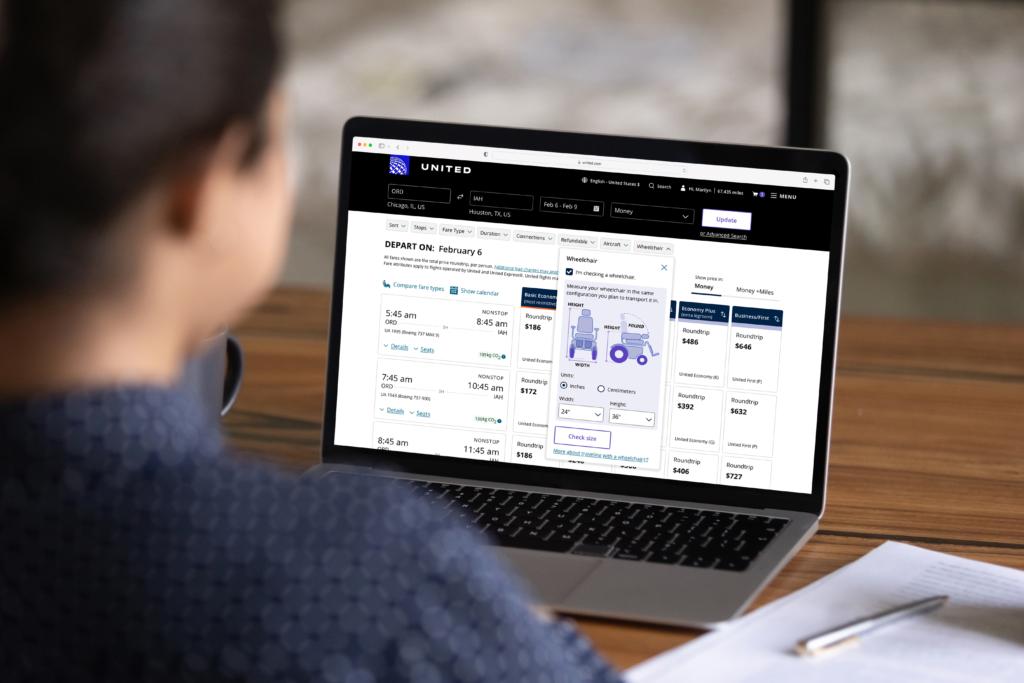

- Applicants must list all social media profiles used in the past five years on the online nonimmigrant visa application (Form DS-160).

- Those accounts must be switched from private to public so consular officers can view content during visa processing.

- The DS-160 already includes a section for usernames on platforms such as Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), Instagram, LinkedIn, and TikTok.

- The State Department describes the identifiers process on travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/us-visas/visa-information-resources/social-media-identifiers.html, making clear that consular staff will review applicants’ digital trails as part of normal security checks.

“A visa is a privilege, not a right,” the State Department says, framing the change as part of a wider push to use “all available information” to judge safety and security risks.

Who is affected

- H-1B visa seekers (tech professionals, international researchers, etc.)

- H-4 dependents (spouses, children)

- Former students moving from F-1 / M-1 status into the H‑1B pipeline (many of whom already supplied social media identifiers)

- Nationals from countries with high H‑1B application volumes, notably India, and Indian-origin professionals living abroad (NRIs) seeking U.S. work visas

Practical consequences and concerns

- Posts, comments, photos, hashtags, and group membership can now inform visa decisions in addition to degrees and job offers.

- Consular officers have wide discretion to refuse nonimmigrant visas when they doubt intent, background, or credibility. That discretion now extends to applicants’ social media content.

- For H‑4 dependents, social activity by spouses or children (including jokes, satire, or dark humor) could raise red flags.

- Applicants worry about “double screening” where accounts previously submitted for student visas are re‑examined under stricter employment‑visa standards.

What officers may look for

Based on prior student‑visa guidance and the State Department’s approach, consular staff may check for:

- Praise of extremist groups or support for violence

- Links to accounts flagged by security agencies

- Inconsistencies between what applicants claim (jobs, schools, travel) and what appears on social profiles (e.g., LinkedIn, Facebook)

- Membership in online groups or posts that could appear “suspicious, extremist, inconsistent, or anti‑American”

If timelines, employers, or locations do not match details in the Form DS-160 or the H‑1B petition, that mismatch can raise questions about honesty — even if the difference is harmless.

Risks of limited or no online presence

- Applicants with almost no social media footprint may be asked why they have no accounts or why profiles are locked.

- A completely blank footprint, or a sudden shutdown of accounts right before an interview, could be treated as a warning sign.

- Applicants now face a trade‑off: profiles must be open enough for review, but not chaotic or risky.

Impact on processing times and hiring

- Processing times may lengthen. Cases can be placed into administrative processing (weeks or months) when officers want additional review.

- Applicants may be called back for second interviews to provide context, translations, or explanations of old posts.

- In some cases, visas may be refused with only a brief reference to security law sections.

- Employers face added unpredictability in H‑1B hiring (lottery caps, wage rules, consular backlogs were already challenges).

- Delays or refusals can affect project timelines and client contracts, particularly for Indian IT firms and consultancies that transfer staff internationally.

Privacy and civil‑liberties concerns

Privacy advocates warn the policy:

- Forces people to make social media profiles public, exposing them to both government scrutiny and online harms (scammers, stalkers, harassment).

- Blurs the line between state security and personal expression, especially around religion and politics.

- Pressures immigrants to self‑censor, unfriend contacts, or avoid sharing content that could be misunderstood across language or cultural lines.

Advice from lawyers and advisers

Immigration lawyers are advising clients to prepare early. Common recommendations include:

- Make a written list of all social media platforms used in the last five years, including old or inactive accounts.

- Carefully review public profiles line by line; correct dates, job titles, and factual errors.

- Archive or hide posts that could be misunderstood, but avoid mass deletion that might appear like a cover‑up.

- Ensure DS-160 entries match online information (timelines, employers, locations).

The State Department’s DS-160 guidance is available through the official portal: DS-160 online nonimmigrant visa application

Some attorneys emphasize not panicking: U.S. consulates have long used open‑source checks (Google searches, press reports, public records). The difference now is the formalization and breadth of the review. Most applicants who tell the truth and keep online profiles consistent with their real lives are likely to pass screening, though the process will feel more intrusive.

Broader effects on migration choices

- Some skilled workers may consider alternate destinations (Canada 🇨🇦, Europe, parts of Asia) or remote work options to avoid U.S. consular scrutiny.

- Recruiters report a growing number of candidates who weigh privacy and state access to social media when choosing where to relocate.

Specific concerns for students moving to H‑1B

- Student advisers are updating briefings for F‑1 students who plan to apply for H‑1B after graduation.

- Online behavior during college (dorm posts, campus debates, TikTok clips) can follow students into the job‑visa phase.

- Students who previously provided social media identifiers should expect those accounts to be reviewed again when seeking work status, potentially under stricter standards linked to technology or sensitive know‑how.

Human impact and everyday choices

Many applicants describe the feeling that the border has moved into their phones. What was once a space for casual conversation, political debate, or satire can now feel like part of an immigration file.

- Some delete old jokes; others move to private messaging apps or closed groups.

- The requirement to keep accounts public for visa purposes limits how far people can retreat from social platforms.

- As December 15, 2025 approaches, H‑1B visa seekers, H‑4 dependents, employers, and students are adjusting online and offline plans to account for a reality where a single post can affect where a family will live.

Starting December 15, 2025, H-1B applicants and H-4 dependents must list all social media accounts used in the past five years on Form DS-160 and make those profiles public for consular review. Officers will check posts for extremist content, inconsistencies with declared information, or security risks. The change may lengthen processing times, prompt second interviews, or increase visa denials. Lawyers recommend auditing profiles, aligning DS-160 entries with online information, and avoiding mass deletions that look suspicious.