- Detention numbers have soared, with the population approaching 70,000 people across 212 facilities.

- Detainees maintain rights to legal counsel and medical care despite restricted conditions and transfers.

- A record-breaking 32 deaths in 2025 highlight an urgent need for medical oversight and accountability.

Right explained: People in ICE detention generally have the right to seek release from custody, to be represented by a lawyer at their own expense, to a bond hearing in many (but not all) cases, to communicate with counsel and family, and to request medical care and protection from abuse while detained.

These rights matter more now because detention has expanded to historic levels. As of January 14, 2026, the detained population is approaching 70,000.

Official ICE figures showed 68,990 people in custody on January 7, 2026, spread across 212 facilities. That is up from about 36,000 in December 2023, and slightly above mid-December 2025 levels. The government has also moved toward a funded daily capacity of about 100,000 beds.

At the same time, safety concerns have grown. Reports described four deaths in the first 10 days of 2026, and 2025 as a record year with at least 32 deaths. Those are in-custody deaths that place a spotlight on medical access, oversight, and accountability.

What follows is a practical rights guide. It explains who has which rights, the main legal bases, how to assert them, and what to do when they are violated.

1) The scale of detention affects how fast you must act

ice detention expansion is not just a policy issue. It changes the daily reality in jails and tent facilities. More people in custody often means slower mail, slower medical appointments, and delayed attorney calls.

It can also increase pressure to sign paperwork quickly. As detention levels climbed toward 70,000, advocates and families have reported more transfers, more remote facilities, and limited access to counsel. Those conditions can cause people to miss court dates or deadlines.

The most protective step is often simple: assert your rights early, in writing when possible, and keep copies.

2) Where people are held: 212 facilities and a push toward 100,000 beds

As of January 7, 2026, ICE reported 68,990 people held across 212 facilities nationwide. These include county jails, private detention centers, and dedicated ICE facilities. Placement can change quickly.

Congress can fund detention at large scale. The administration has described moving toward a funded daily capacity around 100,000 beds. That number matters because expanded capacity can reduce incentives to release people while cases are pending.

Facility location affects legal strategy. It can also affect which federal circuit court law applies if you later seek review of a bond decision.

3) Funding and policy drivers: OBBBA and rapid capacity growth

The “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (OBBBA) was signed July 4, 2025. It reportedly allocated $45 billion toward increasing ICE detention capacity. Officials have framed expansion as increasing operational capacity and “restoring integrity” to the system.

Public statements reflect this stance. DHS Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin said on January 3, 2026, that funding supported staffing growth: “an additional 12,000 ICE officers and agents,” a “120% increase” in months. DHS Secretary Kristi Noem also criticized some unannounced oversight visits as disruptive, in a January 8, 2026 statement.

Even when policy is enforcement-forward, legal rights in detention still exist. The challenge is exercising them in restrictive conditions.

4) Who is in detention now: more people with no criminal record

One of the most important shifts is who is being detained. ICE statistics and public analysis reported that the share of detainees with no criminal record rose from 6% (January 2025) to 41% (December 2025).

That matters for bond and custody arguments. Immigration law does not require a criminal conviction for detention in many situations. But lack of criminal history may support arguments about flight risk, danger, and discretion.

It also affects families. People with long community ties may be swept into detention through worksite actions, traffic stops that lead to ICE contact, or “at-large” arrests.

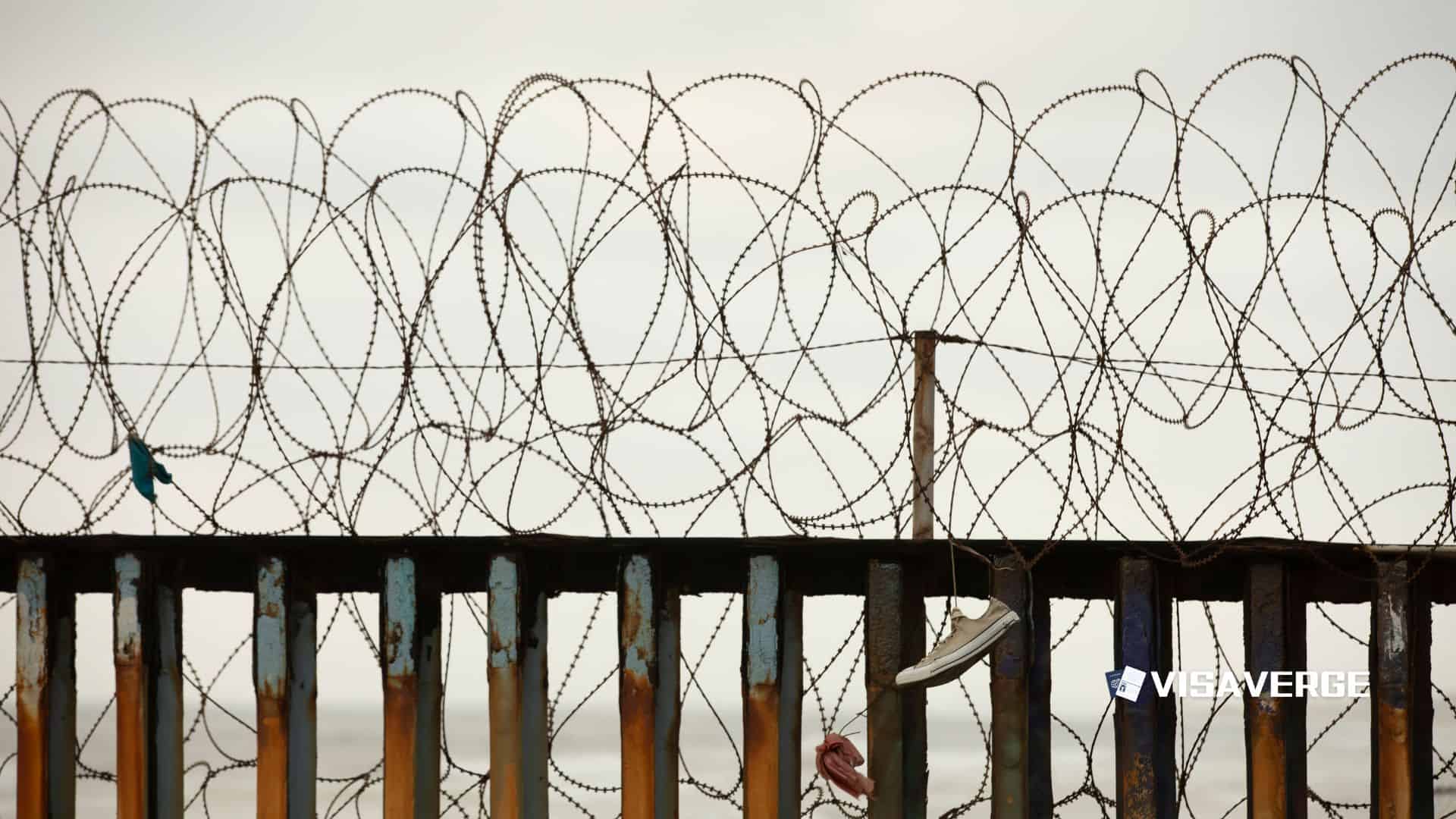

5) New facilities and conditions: including tent camps

To house the surge, the government has relied on “hastily-constructed tent camps.” One named example is Camp East Montana at Fort Bliss, Texas.

Conditions can affect the ability to prepare a case. Tent or temporary facilities may limit private attorney calls, access to law libraries, and continuity of medical care. Transfers can separate detainees from evidence and witnesses.

If you are transferred, your court may change. Your hearing location is usually tied to where ICE is holding you.

Warning: Transfers can happen with little notice. If you have a lawyer, ask them to file a notice of appearance and request advance notice of any transfer. Families should keep the detainee’s A-number and check location often.

6) Deaths, safety, and oversight: the right to medical care and to report abuse

Reports indicate four deaths occurred between January 3–9, 2026, and 2025 had at least 32 deaths in ICE custody. A separate report said facility inspections fell by over 36% in 2025 even as detention increased.

DHS has stated detainees receive meals, medical treatment, and chances to communicate with lawyers and family. Still, the reported rise in in-custody deaths underscores why detainees and families should document medical requests and escalate concerns.

Legal foundations (high level)

Detained noncitizens may assert constitutional protections. The Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause applies in removal proceedings. Courts have long treated immigration detention conditions as subject to constitutional limits.

The precise standards can vary by jurisdiction and posture. There is also a statutory and regulatory framework for custody decisions and detention reviews, including:

- INA § 236 (apprehension and detention pending removal proceedings)

- INA § 241 (detention after a final order of removal)

- 8 C.F.R. § 236.1 (custody and bond procedures)

- 8 C.F.R. § 1003.19 (immigration judge authority over bond in many cases)

Bond eligibility is complex. It often turns on the detention statute ICE is using.

Warning: Some people are in mandatory detention under INA § 236(c). Many in that category cannot get an immigration judge bond. They may still seek other custody review options, including habeas in federal court.

7) The practical rights guide: who has what right, and how to exercise it

A. The right to a lawyer (but not government-paid)

Who has it: People in removal proceedings, including undocumented people, visa holders, and lawful permanent residents (LPRs).

Legal basis: INA § 292 (right to counsel at no expense to the government); also reflected in EOIR practice rules and the Fifth Amendment due process framework.

How to exercise it:

- Tell ICE and the court you want time to find counsel.

- Ask the immigration judge for a continuance to obtain counsel.

- Call family to help retain counsel and gather documents.

Common waiver trap: Accepting “expedited” options without counsel. Some people sign removal or “voluntary return” paperwork under pressure. If you do not understand a form, say so.

Deadline warning: Missing an EOIR court date can lead to an in absentia removal order under INA § 240(b)(5). If you are moved, confirm your next hearing date immediately.

B. The right to a bond hearing in many cases

Who may have it: Many people detained under INA § 236(a).

Who may not: Many people ICE classifies under mandatory detention (INA § 236(c)), certain arriving noncitizens, and some people in post-order detention under INA § 241.

Legal basis: INA § 236; 8 C.F.R. §§ 236.1, 1003.19.

Key precedent: Matter of Guerra, 24 I&N Dec. 37 (BIA 2006) (bond factors such as danger and flight risk).

How to exercise it:

- Ask for a bond hearing as early as possible.

- Prepare documents showing ties and stability: leases, pay stubs, tax records, school letters, medical records, and letters of support.

- Propose a reliable sponsor and address.

Common waiver trap: Agreeing to stipulated removal or accepting removal to “get out” can end the bond issue. Detention is sometimes used as pressure to concede.

C. The right to request release in other ways

Even when bond is unavailable, some detainees may seek:

- Prosecutorial discretion and release decisions by ICE.

- Parole in limited contexts, especially for certain arriving individuals.

- Habeas corpus review in federal court to challenge unlawful detention.

Your options depend on the detention authority and circuit law. Discretionary releases reportedly fell sharply in 2025, but requests may still be appropriate.

D. The right to a fair removal hearing

Who has it: People in removal proceedings.

Legal basis: INA § 240; Fifth Amendment due process.

How to exercise it:

- Ask for an interpreter if needed.

- Ask to review evidence.

- Object if you do not understand the judge or the government’s allegations.

- Apply for relief if eligible, such as asylum (INA § 208), withholding (INA § 241(b)(3)), CAT protection, or cancellation (INA § 240A).

Common waiver trap: Conceding removability without checking whether DHS charged the right statute. LPRs and some visa holders may have defenses that require careful analysis.

E. The right to medical care and to report unsafe conditions

Who has it: Everyone in ICE custody, including undocumented detainees.

Legal basis: Constitutional due process principles; detention standards and internal complaint systems.

How to exercise it:

- Make medical requests in writing and keep copies.

- Ask family to call the facility and ICE ERO and keep a call log.

- If there is an emergency, request immediate evaluation and document who you told.

Common waiver trap: Not documenting requests. Later disputes often turn on records.

8) What to do if rights are violated: a step-by-step escalation plan

- Document immediately. Write dates, names, badge numbers, and witnesses. Keep copies of sick-call slips and grievances.

- Tell your lawyer quickly. If you do not have one, ask family to seek counsel or legal aid.

- Raise the issue in immigration court. Judges may address access-to-counsel problems, scheduling, and fairness concerns.

- File complaints with oversight bodies. Many complaints can be routed through DHS channels, including the DHS Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties and the DHS Office of Inspector General.

- Consider federal court options. Some unlawful detention and conditions claims are brought through habeas or civil actions. These are complex and jurisdiction-dependent.

Warning: Do not rely on verbal promises. Ask for written confirmation of requests, including medical follow-ups and attorney-call access.

Official government data and updates (where families often start)

Sources families often consult include official ICE and DHS pages and immigration court information.

- ICE detention statistics

- ICE newsroom (including death reports)

- EOIR Immigration Court information: EOIR

- DHS press releases

- USCIS newsroom: USCIS Newsroom

Finding legal help quickly

AILA lawyer referral: AILA Find a Lawyer

Other resource: Immigration Advocates Network legal directory.

If detention is involved, time and venue matter. A qualified immigration attorney can assess bond eligibility, circuit-specific detention case law, and relief options.

⚖️ Legal Disclaimer: This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.

This report details the massive expansion of ICE detention, reaching nearly 70,000 individuals by January 2026. It explores the legal rights of detainees, including access to counsel and bond hearings, while highlighting the dangers of increased mortality rates and reduced oversight. It provides a practical guide for families to navigate facility transfers, document medical needs, and assert constitutional due process protections during removal proceedings.