- Immigrants in Maine retain enforceable due process rights during large-scale federal enforcement operations and sudden facility transfers.

- Operation Catch of the Day displaced 60 detainees from Cumberland County Jail to facilities across New England.

- Families must track A-numbers and locations immediately to prevent disruptions in legal representation and medical care.

(PORTLAND, MAINE) — Immigrants in federal custody in Maine—including people held at the Cumberland County Jail—have specific, enforceable rights in immigration detention and removal proceedings, even during fast-moving enforcement actions like “Operation Catch of the Day.”

This guide explains the core rights most likely to matter when ICE conducts arrests and rapid transfers, the legal basis for those rights, who has them, and how to assert them in practice.

It also explains how rights are commonly lost or waived, and what families can do when someone suddenly disappears into the detention system.

Callout — Urgent warning: If ICE transfers someone out of state, phone access, mail, and attorney contact can be disrupted for days. Families should start documenting names, A-numbers, dates, and facilities immediately.

1) Overview of Operation Catch of the Day: what it is, and why it matters

“Operation Catch of the Day” is a statewide federal immigration enforcement action that DHS and ICE announced in connection with arrests across Maine.

The operation began January 20, 2026, and officials described it as targeting people with certain criminal convictions.

The issue escalated in Portland, Maine, when ICE conducted a sudden, large-scale transfer of immigrant detainees from the Cumberland County Jail on January 22, 2026. Reports described roughly 60 people being moved. ICE also described nearly 50 arrests on the first day and a target list of around 1,400 people statewide.

A mass transfer matters beyond the people detained. It affects children, spouses, employers, medical providers, and community services.

It also affects lawyers, because removal defense is time-sensitive. Transfers can disrupt filings, court appearances, and evidence collection.

The right at the center here is due process. Immigration enforcement is civil, but it must still follow the Constitution and the statutes Congress enacted.

The Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause applies to “persons,” not only citizens. That includes many undocumented people.

2) Official statements and messaging: why the framing affects real cases

DHS and ICE publicly framed Operation Catch of the Day as a public-safety initiative. Officials used “priority target” language and emphasized convictions they described as serious.

DHS also promoted a public-facing “worst of the worst” portal at wow.dhs.gov.

This messaging can matter inside an immigration case. Prosecutorial narratives can influence custody decisions, including whether ICE seeks detention and how it opposes bond.

Immigration Judges make individualized decisions, but they often rely on records of conviction, police reports, and litigation positions.

At the same time, families and counsel often experience a different reality on the ground. Rapid transfers can prevent quick attorney access and create confusion about where someone is detained.

That confusion can cause missed deadlines, including bond filings and emergency motions.

Key point: Labels in press releases are not findings of removability. In court, DHS must still prove its charges by the required standard, and the person still has the right to contest them. See INA § 240.

3) Operational timeline and actions: what “transfer” usually means in immigration detention

Based on reported timing, the enforcement surge began January 20. ICE then moved all immigrant detainees out of Cumberland County Jail on January 22.

In immigration detention, a “transfer” typically means ICE transports a detained person to a different facility. The person may be re-booked under new rules. Phone access can change immediately.

Commissary, mail procedures, and visitation can change too. Attorney visitation policies also vary by facility.

Common immediate consequences include:

- A family suddenly cannot reach the person at the old jail.

- The person’s property and paperwork may be separated from them.

- A scheduled legal call may be canceled.

- A planned court filing may be delayed.

- Medical appointments may be interrupted.

The right implicated here is access to counsel and a fair hearing. Noncitizens have the right to be represented, at no expense to the government. See INA § 292; 8 C.F.R. § 1240.10(a)(1)–(2).

Transfers can make that right harder to exercise, but it still exists.

Callout — Deadline warning: Immigration court deadlines can be extremely short. A missed filing can have lasting consequences. If someone is transferred, counsel should confirm the court location and deadlines the same day.

4) Targeting data and scope: what “target lists” can mean, and why categories matter

ICE officials described identifying a target list of about 1,400 individuals in Maine. In general, “target lists” in enforcement operations may be built from databases and records checks.

They may include prior removal orders, criminal history entries, and local data-sharing. The precise inputs vary and are not always public.

For detained people, the most important distinction is between:

- Allegations (what an agency claims),

- Charges (what DHS files in the Notice to Appear), and

- Convictions (what a court record actually shows).

These distinctions matter because criminal history can affect whether DHS argues someone is subject to mandatory detention under INA § 236(c).

They also affect whether DHS argues a person is a danger or flight risk in bond proceedings under INA § 236(a), and whether they are barred from certain relief depending on the conviction category.

Even when DHS cites “aggravated” conduct in public messaging, the legal term “aggravated felony” has a specific definition in INA § 101(a)(43). A public description may not match the statutory category.

How to exercise the right in practice: Ask counsel to obtain certified conviction records and charging documents. Do not rely on summaries or online entries alone.

A bond strategy often depends on the exact statute of conviction.

5) Context, policy, and local-federal tension: 287(g), detainers, and “uncooperative” labels

Local officials in Maine publicly criticized aspects of federal tactics, including concerns about warrants, transparency, and real-time information sharing.

Federal officials also criticized Maine leadership and described Portland and Cumberland County as “uncooperative.”

In practice, cooperation disputes often center on whether local jails honor ICE “detainers,” whether local agencies share release-date data, and whether a jurisdiction participates in 287(g).

What 287(g) is: INA § 287(g) allows DHS to enter agreements with local agencies so trained local officers can perform certain immigration enforcement functions under federal supervision. Some jurisdictions decline these agreements.

Federal officials may use “uncooperative” labels to explain enforcement posture.

Detainers are different: An ICE detainer is typically a request to hold someone for up to 48 hours beyond their release time, excluding weekends and holidays. See 8 C.F.R. § 287.7.

Whether and how detainers are honored can vary by state law, policy, and local practice.

Callout — Rights warning: In civil immigration enforcement, you may not get Miranda warnings. Anything you say to officers can still be used in immigration proceedings. You can decline to answer questions.

6) Impact on detainees and transfer destinations: counsel access, court logistics, and medical hardship

Reports stated that people were moved from Maine to facilities in nearby New England states, including Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island.

Even “nearby” transfers can be devastating for families without transportation, childcare, or time off work.

Access to counsel: Transfers can separate people from local attorneys. They can also increase costs and delay legal visits.

While remote legal calls may be available, they can be limited by facility rules and scheduling.

Court scheduling: A transfer does not always change where the immigration case is docketed immediately. Sometimes the court remains the same but hearings move to video. Sometimes venue litigation follows.

These questions can be complex and fact-specific.

Medical and mental health care: Detained people retain constitutional protections against deliberate indifference to serious medical needs under due process principles.

They may also have protections under ICE detention standards, which guide medical screening and ongoing care. However, standards do not always create a private right to sue. Remedies often require fast, attorney-driven action.

Emergency court intervention: Reports described a federal judge issuing a last-minute order affecting at least one person’s transfer, while records later indicated the person had already moved.

Emergency motions, including temporary restraining orders, may sometimes pause a transfer or require access to counsel. They do not automatically end removal proceedings, and courts may limit relief based on jurisdiction and the claims raised.

7) Public disclosure and transparency tools: how to verify facts and avoid misinformation

During enforcement surges, misinformation spreads quickly. Readers should prioritize official sources, but also interpret them carefully.

WOW portal (wow.dhs.gov): DHS describes this as a public-facing tracker highlighting certain arrests and criminal records. Families should not assume that a listed entry reflects final court outcomes.

In immigration court, removability and relief are still adjudicated case-by-case.

Agency newsrooms: Start with DHS and ICE press releases to confirm operation names, dates, and claimed scope.

Facility pages: For detention logistics and contact information, use official ICE facility pages. For Cumberland County Jail, the ICE listing is here: https://www.ice.gov/detain/detention-facilities/cumberland-county-jail

How to exercise rights using these sources: Once you confirm the facility, ask counsel to contact the facility’s legal visitation line. Counsel can also file a Form G-28 appearance and request records.

8) Official sources and a verification checklist: what families should do next

When someone is arrested or transferred during a multi-day operation, conditions can change hour by hour. Use a simple verification flow and keep written records.

Verification flow (practical checklist):

- Confirm the operation details. Use the DHS or ICE newsroom.

- Confirm the facility’s official contact pathway. Use the ICE detention facility page.

- Confirm the court posture. Speak with an attorney and check EOIR court information, when applicable. EOIR’s public information is at https://www.justice.gov/eoir

- Track identifiers consistently: full legal name, date of birth, A-number, arrest date, and last known location.

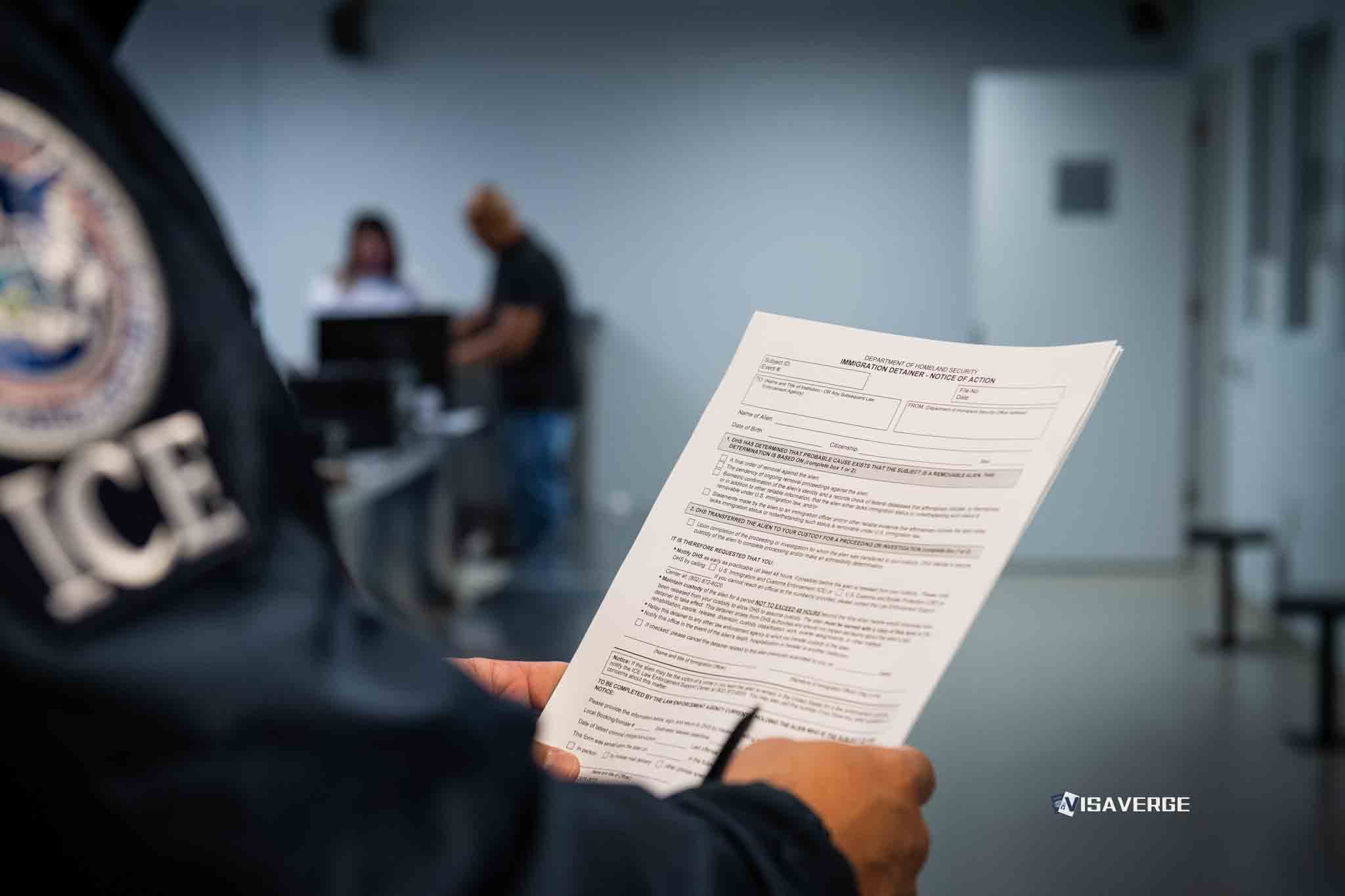

- Save documents and screenshots: Notice to Appear, detainer paperwork, bond paperwork, and medical requests.

Common ways rights get waived or lost:

- Signing papers you do not understand, including “stipulated removal” or voluntary departure forms.

- Missing hearings due to confusion after a transfer.

- Giving statements about immigration status or criminal history without counsel.

- Failing to update the immigration court with a correct address. See INA § 239(a)(1)(F).

If you believe rights were violated: Document what happened, identify witnesses, and consult an immigration attorney immediately. Some remedies require emergency filings, and options can vary by federal circuit and by detention location.

Legal help resources

– AILA Lawyer Referral: https://www.aila.org/find-a-lawyer