Wednesday, February 4, 2026

1) Incident Overview

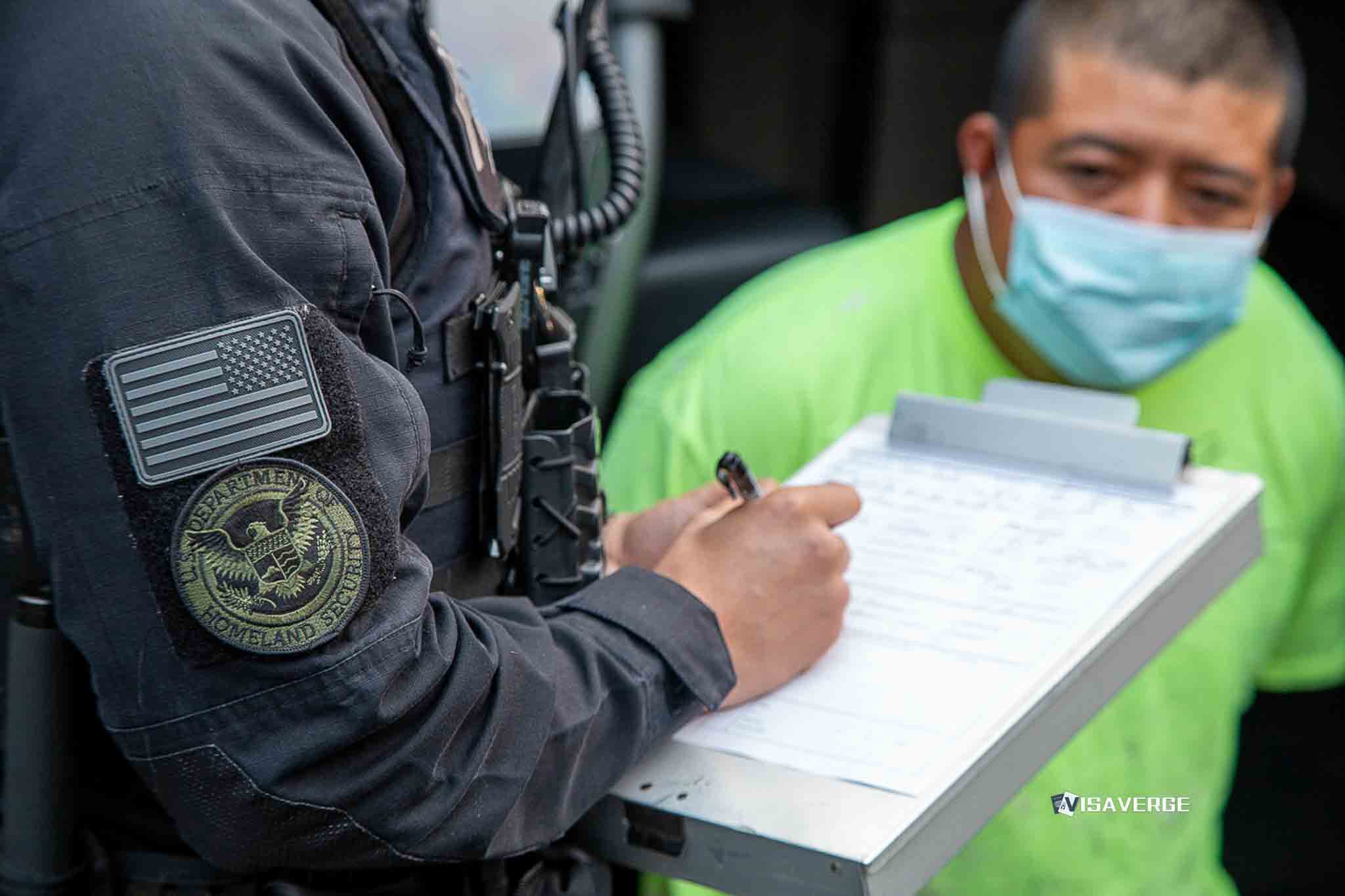

A Philadelphia-area retiree received a rapid administrative subpoena and later a home visit after sending a pointed email to a DHS prosecutor.

That sequence—criticism, swift data demand, then in-person contact—has drawn scrutiny of administrative subpoena authority and the risk that investigative tools can chill speech in immigration-adjacent disputes.

Late in 2025, the 67-year-old U.S. citizen emailed a Department of Homeland Security (DHS) prosecutor about an Afghan refugee case. Within hours, his email provider notified him that DHS had sought account information. Days later, federal investigators appeared at his home in the Philadelphia suburbs.

Speed matters in civil-liberties debates. Fast escalation after political or policy criticism can look like retaliation, even if the agency frames it as routine investigative work. That tension sits at the center of this case.

2) Official Statements and Responses

Tricia McLaughlin, a DHS spokesperson, publicly framed the request as tied to criminal enforcement. On February 3, 2026, she said: “This subpoena was part of a criminal investigation. Homeland Security Investigations has broad administrative subpoena authority under the law.”

Homeland Security Investigations, a DHS investigative component, is distinct from benefits agencies and typically focuses on enforcement and investigations. In that context, an administrative subpoena functions as a compulsory demand for records or testimony issued inside the agency process.

Investigators who later visited the citizen reportedly said they were acting at the direction of DHS headquarters in Washington, D.C. They also reportedly relayed that the prosecutor may have “felt threatened” by the email’s wording. At the same time, investigators reportedly told the citizen he had committed no crimes.

A core point for readers: an administrative subpoena is not the same as a judge-approved search warrant. A warrant is signed by a judge and usually requires probable cause. An administrative subpoena is generally issued without that judge’s signature at the moment of issuance.

Official statements framed this as part of a criminal investigation; investigators reportedly told the citizen he had committed no crimes while also indicating the prosecutor felt threatened.

3) Case Facts and Personal Details

Jon, identified only by his first name, is a 67-year-old retired insurance professional and a naturalized U.S. citizen originally from the U.K. He lives in the Philadelphia suburbs.

Pressure often rises in immigration matters where removal could mean serious harm. Jon’s email centered on an Afghan refugee, described as fearing death if deported to Taliban-controlled Afghanistan. Jon urged caution and leniency in the handling of the case.

Tone can be read differently once law enforcement gets involved. Jon described the email as “polite but firm,” while investigators later treated its phrasing as potentially threatening. The email included: “Mr. Dernbach, don’t play Russian roulette with H’s life. Err on the side of caution. Apply principles of common sense and decency.”

That interpretive gap—advocacy versus perceived threat—helps explain why this incident has become a teaching example for how administrative subpoenas can intersect with speech.

4) Subpoena Details and Data Requested

Five hours and one minute after Jon sent the email, he received a notification from Google that DHS had issued an administrative subpoena for his account data. That timing is central to the controversy because it suggests an unusually rapid escalation from criticism to compelled data production.

Provider notifications can appear in different ways. Sometimes a user receives an email or dashboard notice that a government request was made. Other times, the provider may delay notice if a legal gag order or delayed-notice process applies. When notice does come, it often signals one of two things: the provider believes notice is allowed, or a notice-delay period has expired.

Even without the content of messages, account records can be highly revealing. IP addresses can suggest approximate location or travel patterns. Login timestamps can map daily routines. Payment details can link accounts across services. Metadata can show who interacted with whom and when, even if message text is not produced.

Reports described the subpoena as seeking a wide range of identifiers and account-linked information, including records reaching back to a specific date. The full field list and lookback window are best read carefully before drawing conclusions about what could be inferred.

The original article listed specific data categories. An interactive tool will present the reported categories and examples so readers can examine what kinds of account information were sought and why each category raises privacy or investigative concerns.

Timing of provider notices and the scope of identifiers sought can dramatically affect privacy and ability to contest data disclosures.

5) Legal Authority and Process

Administrative subpoenas are compulsory demands issued under an agency’s statutory authority. They are common in regulatory and enforcement systems. Within DHS, they can be used to seek records from third parties, such as technology companies, in immigration or customs-related investigations.

Two statutes were cited as authority in this matter: 8 U.S.C. § 1225 and 19 U.S.C. § 1509. In broad terms, these provisions relate to immigration inspection and customs enforcement tools. They have been read to allow DHS to compel certain information relevant to those functions, including from businesses that hold records.

A judicial warrant is different. A warrant is approved by a judge and typically requires probable cause. An administrative subpoena is often signed within the agency and may use a lower threshold, such as relevance to an authorized inquiry. Standards vary by context, and the subpoena’s wording matters.

| Aspect | Administrative Subpoena | Judicial Warrant | Key Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Who issues it | Typically an agency official | A judge or magistrate | Judge review may not occur at issuance for subpoenas |

| Standard | Often relevance to an authorized inquiry | Probable cause (typical criminal standard) | Warrants usually require a higher showing |

| Typical target | Third parties holding records (providers, businesses) | Places, persons, or items to be searched/seized | Subpoenas often focus on records rather than physical searches |

| Notice patterns | Often provider notice, sometimes delayed | Notice can occur after execution | Notice timing affects a person’s chance to respond early |

| Challenge routes | Often through courts or provider processes | Through court motions and suppression litigation | Both can be contested, but paths differ |

Oversight questions usually hinge on who signed the demand, what legal standard applied, and what mechanisms exist to challenge or narrow it.

In many cases, a provider receiving an administrative subpoena reviews it for legal sufficiency and scope. Affected users may be able to consult counsel about options such as seeking to quash or modify, or pressing for narrowing through provider channels where available. Timelines can be short, and provider practices differ.

If you are contacted by a provider about administrative subpoenas, consult counsel to understand scope and potential objections.

6) Broader Impact, Reactions, and Context

Nathan Freed Wessler of the ACLU framed the concern as a chilling effect. He warned that government power can make people “look over their shoulder,” even without arrests. In this case, Jon reported feeling terrified and worried about being stopped at an airport or placed on a watchlist.

Travel anxiety is a common downstream fear in immigration-related conflicts. People worry that advocacy, complaints, or heated language could lead to additional screening, referrals to secondary inspection, or broader attention during international travel. Those worries can grow when an investigation is paired with a home visit.

Scale also changes how the public judges risk. Transparency reporting has shown that large providers receive large volumes of administrative subpoena requests. Google reported 28,622 such requests in the first half of 2025, and Meta has reported similar categories of demands in its reporting. High volumes do not prove misuse, but they do raise the stakes for clear rules and external checks.

7) Official Sources and Context

Verification starts with primary legal text and official agency statements. Readers typically check three categories of references: (1) statutes, (2) agency public statements, and (3) policy guidance that describes how authorities are used.

Law text is the most stable reference point. For example, the cited statutes—8 U.S.C. § 1225 and 19 U.S.C. § 1509—can be read directly on trusted legal repositories such as law.cornell.edu. Agency statements can be checked through the DHS Newsroom.

USCIS fits into this picture differently. USCIS mainly adjudicates immigration benefits, such as petitions and applications. DHS investigative components, including Homeland Security Investigations, conduct enforcement and investigations. Both sit within DHS, yet their roles differ. USCIS policy manuals describe benefits adjudication standards, not the day-to-day use of investigative subpoenas.

When readers compare agency claims to written authority, the goal is simple: confirm what power is claimed, where it comes from, and which component is exercising it. That approach helps separate benefits questions from investigative actions, even when a case begins with an immigration-related dispute.

The sections “Official Statements and Responses,” “Subpoena Details and Data Requested,” and “Official Sources and Context” will include interactive tools for readers to explore primary statements, subpoena fields, and source documents.

This article discusses legal authorities and civil-liberties concerns. Readers should consult qualified counsel for specific legal questions. Not a substitute for professional legal advice.