- King’s College London withdrew visa sponsorship for student Usama Ghanem following pro-Palestinian protests.

- The U.S. government canceled over 100,000 visas between 2025 and 2026 amid shifting enforcement policies.

- New AI-driven monitoring of social media creates significant legal and academic uncertainty for international students.

(UNITED KINGDOM) — King’s College London withdrew visa sponsorship for Usama Ghanem after his participation in pro-Palestinian protests, triggering a UK Home Office visa revocation and setting off a legal challenge and an academic backlash.

Ghanem, a 21-year-old Egyptian international relations student, launched a judicial review against the university in early October 2025, alleging discrimination and a breach of his human rights.

Over 88 student groups and numerous academics from KCL, SOAS, and Queen Mary University London signed an open letter urging the university to reverse the suspension and calling the action “draconian.”

The letter argued that the stakes go beyond campus discipline because Ghanem “faces a high risk of torture if deported to Egypt,” where it said he was previously imprisoned for political activism.

University sponsorship and visa mechanics in the UK

In the UK, universities that sponsor international students play a formal role in the visa system, because sponsorship links a student’s enrolment to their immigration permission.

When a university withdraws sponsorship, it usually signals that the institution no longer supports the student’s continued stay under the terms of that route. The Home Office then decides what immigration action follows.

That distinction matters in legal challenges. A university’s sponsorship decision is not the same thing as a Home Office decision to revoke a visa, even if one triggers the other.

Judicial review and legal principles

A judicial review generally asks a court to examine whether a decision-maker acted lawfully, followed proper procedure, and stayed within the powers available to it.

Such challenges can test whether a process treated a person fairly, and can also raise discrimination and human-rights issues when a claimant alleges unlawful differential treatment or serious risk on return.

Claims of deportation risk, including alleged torture risk, can change the urgency and legal posture of a case because the consequences of removal can be irreversible.

Public campaigns and institutional context

Public campaigns, open letters, and student group mobilisation often accompany cases like these, but they do not determine the legal outcome. They form part of the public context around institutional choices.

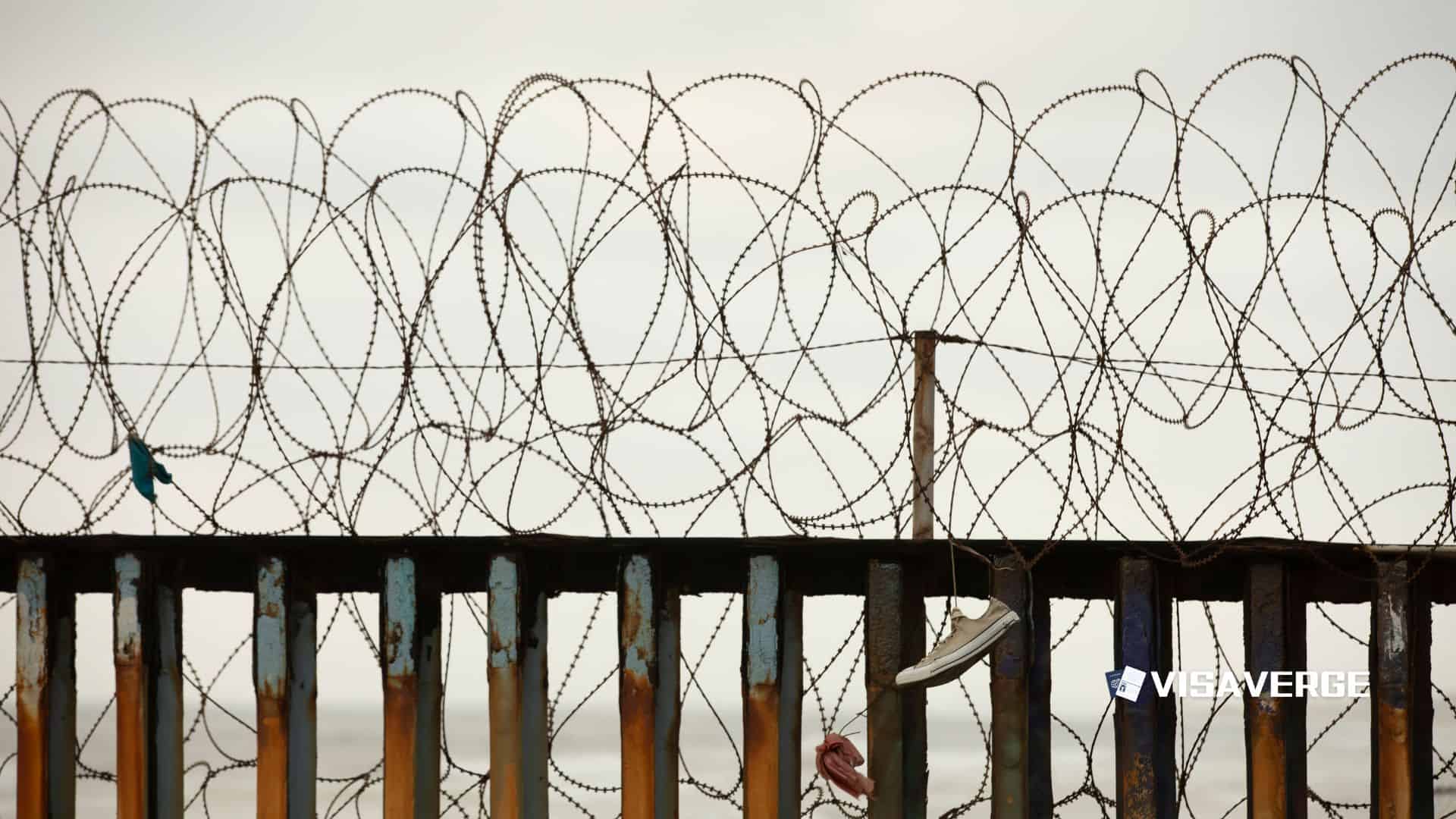

The Ghanem case has also drawn attention because it lands amid a separate, U.S.-driven policy debate over international students, campus activism, and how governments frame visa permission.

U.S. institutional split and policy signals

In the United States, the State Department issues visas, while U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) adjudicates many immigration benefits and status-related requests, and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) oversees enforcement, including through ICE.

That institutional split shapes how policy signals work. A public statement by a senior official can indicate enforcement focus, even when it does not itself change the legal rules.

A USCIS Policy Memorandum, by contrast, is an internal agency document that directs personnel. It typically guides adjudications and operational steps, rather than rewriting statutes.

USCIS memorandum and administrative actions

One USCIS Policy Memorandum dated January 1, 2026, carries the identifier PM-602-0194 and instructs staff on holds and re-review tied to a presidential proclamation.

The memorandum states: “Effective immediately, this memorandum directs U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) personnel to: 1. Place a hold on all pending benefit applications for aliens listed in Presidential Proclamation (PP) 10998. [and] 3. Conduct a comprehensive re-review of approved benefit requests. that were approved on or after January 20, 2021.”

Such language reflects how immigration agencies can treat certain benefits and decisions as subject to later scrutiny, especially when policy priorities shift or new screening steps are introduced.

Public remarks, rhetoric, and examples

In public remarks, Secretary of State Marco Rubio linked student visa permission to campus conduct in comments delivered during an “Official Press Briefing, Guyana, March 27, 2025.”

Rubio said: “We gave you a visa to come and study and get a degree, not to become a social activist that tears up our university campuses. And if we’ve given you a visa and then you decide to do that, we’re going to take it away. … Every time I find one of these lunatics, I take away their visa.”

In separate remarks the next day, delivered “En Route to Miami, March 28, 2025,” Rubio framed visas as discretionary. “No one has a right to a visa. If you have the power to deny, you have the power to revoke. We will do so in cases we find appropriate,” he said.

A DHS spokesperson also pointed to terrorism-related allegations in a statement dated March 28, 2025. “DHS and ICE investigations found [targeted students] engaged in activities in support of Hamas. glorifying and supporting terrorists who kill Americans is grounds for visa issuance to be terminated,” the spokesperson said.

Terminology, process, and practical effects

The interaction between statements like these and policy documents can be hard for students to interpret, particularly because the message can travel faster than the underlying legal authority.

Students and universities also face a terminology problem. “Revocation,” “cancellation,” “holds,” and “re-review” can refer to different actions with different consequences.

In plain practice, “visa cancellation” often points to the entry document in a passport, while “status” concerns whether a person remains lawfully present under the terms of admission and compliance. Enforcement actions can follow either problem.

A “hold” usually means an application stops moving while additional checks, review, or requests for information occur. It can delay work permission, extensions, or other benefits tied to continued status.

A “re-review” indicates an agency revisits approvals already granted. The January 1, 2026 memorandum directs “a comprehensive re-review of approved benefit requests” approved “on or after January 20, 2021.”

Scale and time windows can shape the level of uncertainty for students and institutions. In the U.S. figures cited, the cancellations and review periods span multiple months and involve large numbers.

Between January 20, 2025, and January 10, 2026, the U.S. government canceled over 100,000 non-immigrant visas, including roughly 8,000 student (F-1/J-1) visas.

As of January 1, 2026, USCIS placed a hold on applications for citizens from 39 countries, including those carrying Palestinian Authority travel documents, pending national security reviews.

Monitoring, compliance triggers, and fears

The material describes monitoring as AI-driven programs “often referred to as ‘Catch and Revoke’” used to monitor social media for “foreign policy-conducive” behavior.

Even when public debate focuses on activism, immigration cases can turn on compliance triggers that have little to do with speech, including documentation gaps or allegations of status violations.

At the same time, the material describes fear among students that “minor infractions” like traffic tickets, or political opinions, could lead to “an automatic electronic voiding of their visas.”

Litigation and case examples

Litigation has also entered the U.S. picture. In September 2025, Federal Judge William Young (Boston) ruled that many revocations were an “unconstitutional suppression of free speech,” while the administration continued to appeal and implement new vetting protocols.

Court outcomes in policy-heavy immigration disputes can be uneven, because litigation can challenge process, constitutionality, and agency authority, and outcomes can include rulings, injunctions, appeals, and revised policies.

The direct impact on individuals can be immediate, whether the case involves visa sponsorship in the UK or visa cancellation and enforcement in the U.S.

The material links Ghanem’s case to a wider set of examples, including Rumeysa Ozturk in the U.S., and says students can face immediate loss of legal status.

In the U.S., it says students have been detained by ICE and flown to facilities in Louisiana and Texas, a disruption that can complicate access to counsel and evidence.

Academic and personal consequences

Academic lives can also fracture quickly. Students may lose the ability to attend classes, continue research, or take part in travel for conferences when status questions arise or when they fear extra scrutiny at borders.

Travel decisions become especially fraught when students believe a case is pending, because attempted re-entry can expose unresolved issues and trigger deeper questioning.

Some students consider leaving early, but “self-deportation” decisions can also narrow options. Timing and documentation can shape whether people can challenge decisions or seek re-entry later.

Universities often become the practical first stop for distressed students, whether through international student offices or, where available, legal clinics, but institutional assistance does not replace formal immigration decisions.

Verification workflow and guidance

For readers trying to make sense of fast-moving claims, verification depends on separating primary documents from commentary, and matching quotes to the government entity that can actually take the action described.

A basic verification workflow for a policy memo starts with locating the document on the official site, confirming its identifier and date, and noting any “Effective immediately” language alongside the action it orders.

Readers can also preserve citations by saving PDFs, capturing URLs, and recording access dates, to ensure they can track whether language changes over time.

Conclusion

The Ghanem case remains a UK Home Office matter rooted in university sponsorship powers and a judicial review against KCL, but it now sits in a wider international argument over how far governments and institutions can go when immigration permission intersects with protest.