Culinary education is fast becoming a passport to work abroad for young people in Bangladesh, with training schools reporting steady demand from students aiming for jobs in hotels, restaurants, and cruise ships across the Middle East, Europe, and Australia. Sector trainers say the pipeline is now well established: students complete chef diplomas at home, earn internationally aligned certificates, build early work experience through internships, and then apply for skilled roles overseas where kitchens face chronic staffing gaps.

Scale and outcomes

Each year, about 8,000 students graduate from culinary programs nationwide. Schools estimate 30–40% secure jobs abroad in hospitality roles, including placements in Malaysia, Dubai, Qatar, Europe, and North America. That share represents thousands of families counting on a stable foreign income, and it reflects how culinary education has shifted from a niche interest to a planned route out of youth unemployment.

Parents and students increasingly treat chef training like a practical migration plan rather than a hobby. For many families, this pathway offers a concrete route to foreign earnings that can support household expenses and education for siblings.

Leading institutes and international alignment

Institutes such as the Khalil Culinary Arts Centre, the National Hotel and Tourism Training Institute (NHTTI), the Culinary Institute of Bangladesh (CIB), and the Professional Cooking Academy (PCA) have led the push to match coursework with international benchmarks.

Their programs offer:

– City & Guilds UK-based qualifications

– HACCP and ISO 22000 food safety training

– Coursework aligned with American Culinary Federation standards

These recognized badges matter in embassies and kitchens overseas, where qualifications can influence hiring and visa assessments. Graduates say the certificates help turn a local diploma into a credential that fits employer checklists abroad.

Course structure and skills taught

Course length varies widely to match different budgets and timelines — most programs run 3 months to 18 months. Common curriculum components include:

– Over 120 international recipes and methods

– Menu costing and inventory control

– Knife skills and brigade routines

– Structured food safety modules

Many programs also add spoken English training, a small but important upgrade that helps young cooks pass interviews by phone and communicate confidently during probation abroad. Schools stress workplace habits — mise en place discipline, timekeeping, and safe handling — because mistakes in a commercial kitchen can derail a new hire on day one.

Placement support and career progression

Placement support is built into most diplomas, linking graduates to:

– Internships at local hotels and restaurants

– Referrals for overseas opportunities

That first internship can be the bridge to a job letter; for skilled migration, early experience often matters as much as the diploma. Training centers report structured links with hospitality employers seeking entry-level commis chefs and pastry assistants, particularly in Gulf countries where high-season demand outstrips local supply. Alumni networks also help, alerting schools when ships or resorts are hiring at scale.

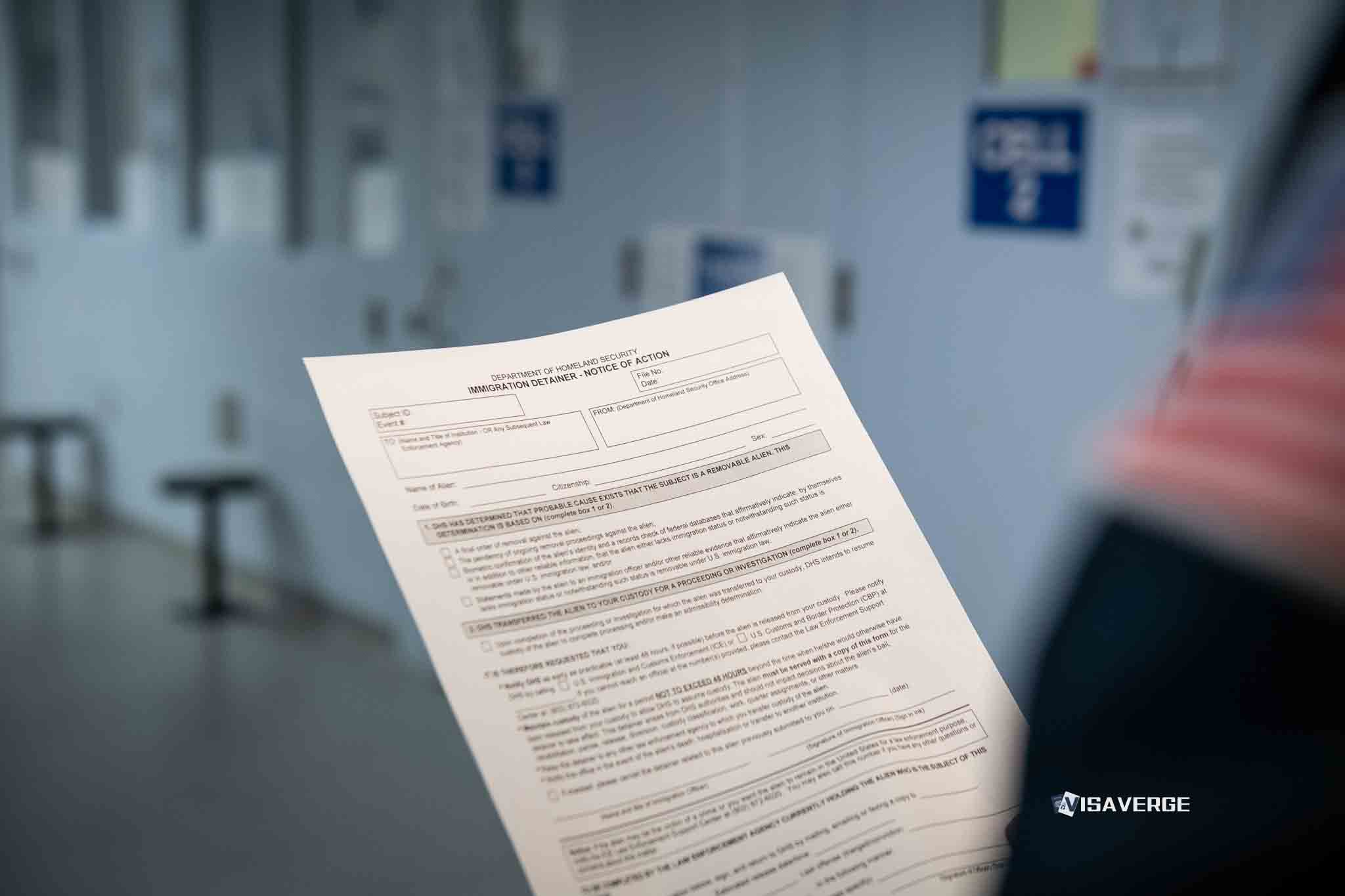

Pathways to Australia and skill assessments

Australia remains a key destination because chef is a recognized skilled occupation and pathways exist for those who meet training and assessment conditions. Students and agents point to the:

– Temporary Graduate visa (subclass 485)

– Skilled Nominated visa (subclass 190)

as examples of routes that align with culinary diplomas and post-study experience. Official guidance for the temporary graduate route is published by Australia’s Department of Home Affairs and explains eligibility criteria, timelines, and conditions for recent graduates on its website.

According to analysis by VisaVerge.com, candidates aiming for skilled migration also plan around a Chef skills assessment that typically includes document review and a technical interview. Sector trainers say the required Chef skills assessment costs around AUD 3,120, a figure students budget for alongside tuition and living costs.

Financial barriers

Money is a major hurdle. Long-form diplomas can cost Tk 300,000 to 500,000 (roughly USD 3,000–5,000), not including uniforms, knives, and exam fees. For many middle-class families, that price forces trade-offs or loans. Trainers say more scholarships or affordable financing would widen access and reduce dropout rates, especially for students outside Dhaka who also face housing expenses in the capital.

Some institutes offer installment plans, but interest and fees can add pressure when a job offer takes longer than expected.

The migration strategy and long-term outlook

The outflow to Australia and Europe builds on a long pattern of placements in Gulf states, where salaries and employer-provided housing can make early savings easier. While not all roles qualify as skilled positions for long-term settlement, the first overseas contract often funds further study, additional certifications, or a second move to a country with a clearer skilled pathway.

For many families, the immediate goal is steady foreign income. Later, if experience and qualifications align, pursuing permanent residence becomes an option.

Weaknesses and calls for reform

Educators and employers identify several weaknesses in the model:

– National curricula need frequent updates to match evolving international standards, including modern food safety systems and sustainability practices.

– Students fall behind if syllabi lag behind hotel and brand requirements.

– Better coordination between government bodies and hotel groups could align training outcomes with real hiring needs.

Money and access are additional issues. More scholarships, affordable financing, and lower training costs would increase participation and reduce dropouts.

“Transparent course outlines, documented internships, and verifiable certificates give parents something measurable to trust.”

Success stories and local reinvestment

Visible success stories motivate new cohorts. For example, Khalilur Rahman, a Bangladeshi-American chef named Personality of the Year at the British Curry Awards in 2022, returned to open a training center and raise local standards. Alumni who have cooked on cruise liners or in five-star properties share lesson plans, donate equipment, and mentor students through interviews and trial shifts.

These returns show how global kitchen experience can come home to improve facilities and lift the next generation.

Employer perspective

For hiring managers overseas, the draw is a steady supply of cooks trained in:

– High-volume production

– Disciplined food safety practices

Hotels and cruise ships prefer recruits who can plug into existing systems with minimal retraining. That alignment is why programs invest in HACCP and ISO 22000 modules and adopt UK and US curriculum frameworks. Schools are also expanding tracks in pastry, butchery, and cold kitchen to fill persistent shortage lists.

What’s needed to scale the model

Educators recommend:

– Standardized national competencies endorsed by industry

– Regularly refreshed syllabi tied to employer needs

– Richer data on graduate outcomes to guide families and students

Such measures would lift graduate quality, reduce confusion among foreign employers, and help families decide which diploma offers the best chance of a timely job offer.

Human impact and conclusion

The human stakes are clear in classrooms where students dream of sending money back for parents’ medical bills or younger siblings’ school fees. Culinary education offers a map that feels concrete: learn a trade, pass recognized assessments, and turn “work abroad” from an idea into a job with a start date.

If local training keeps pace with global standards — through updated curricula, lower costs, and stronger employer links — more young cooks can carry their craft across borders and build steady futures through honest work. In kitchens from Doha to Sydney, the journey often begins in local classrooms with borrowed knives and a practiced julienne.

This Article in a Nutshell

Culinary training in Bangladesh now serves as a structured route to international hospitality jobs, with around 8,000 annual graduates and 30–40% placed overseas. Leading institutes align courses to City & Guilds and food-safety standards, include internships and English training, and support placements in Gulf states, Malaysia, Europe, and Australia. Costs—diplomas and a typical Australian skills assessment—pose barriers. Calls for updated curricula, financing, and stronger industry coordination aim to boost access and employer alignment.