- A Texas high school student and her mother were detained during a routine ICE check-in in San Antonio.

- Noncitizens generally retain the right to remain silent and consult an attorney under the Fifth Amendment.

- Immigration check-ins carry inherent risks of immediate detention depending on an individual’s specific legal posture.

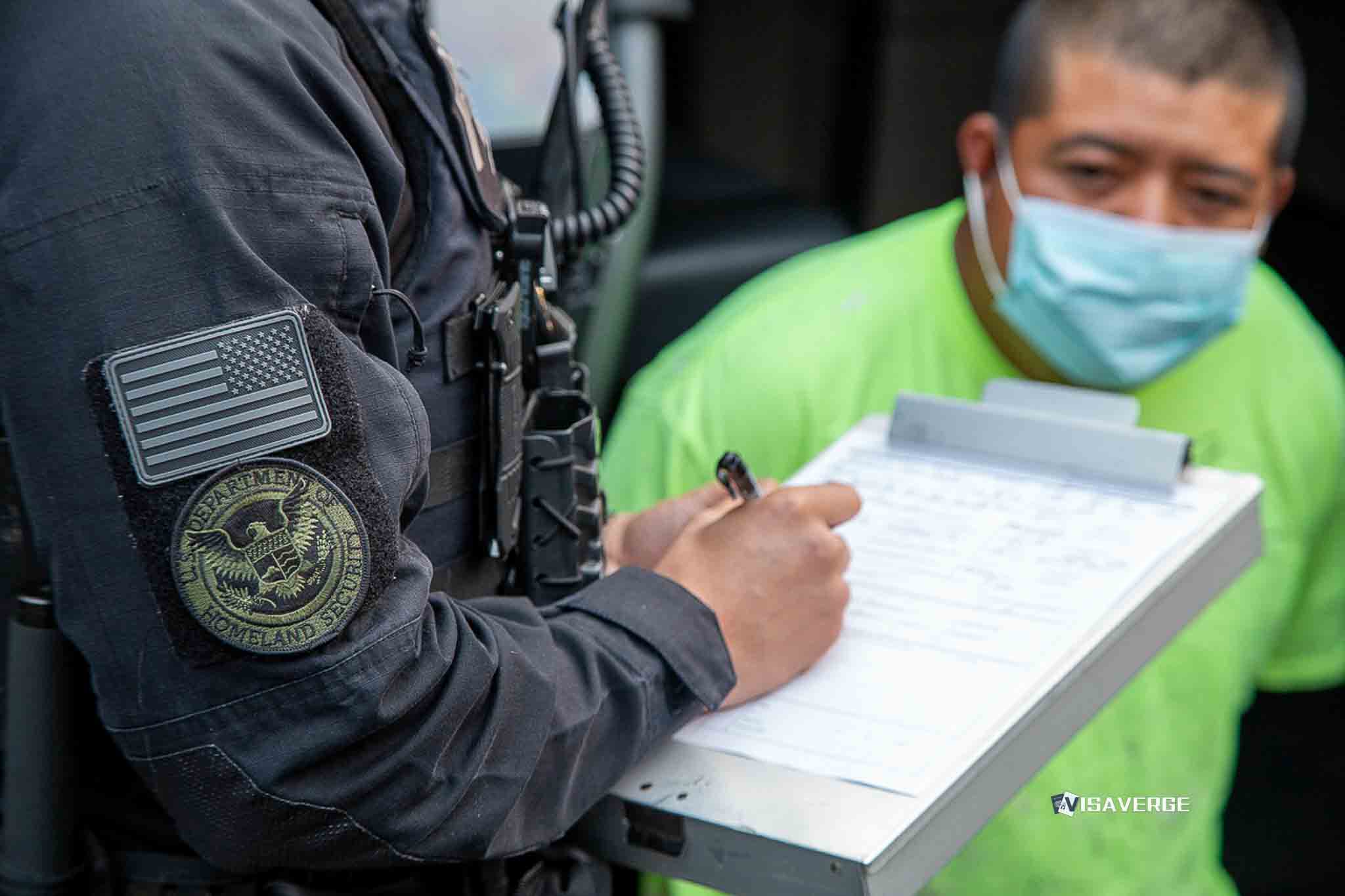

(SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS, USA) — If you have an ice immigration check-in scheduled, you generally have the right to remain silent and to speak with an attorney before answering questions that could be used against you, even if you are not a U.S. citizen.

That core protection flows from the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination and long-standing due process principles. In immigration custody, the government must also provide basic procedural safeguards, including notice of charges in removal proceedings. See INA § 239; 8 C.F.R. § 1240.10 (advisals in removal proceedings).

At the same time, immigration law does not guarantee government-appointed counsel in most immigration cases. See INA § 292 (right to counsel at no expense to the government).

A recent report out of San Antonio illustrates why these rights matter in real life: a high school senior and her mother reportedly went to what they believed was a routine ICE check-in and were detained instead of released. Families across Texas attend such appointments expecting to return home that day. When detention happens instead, the legal and practical stakes can change in minutes.

1) Incident overview: a “routine” check-in that ended in detention

According to local reporting, a Texas high school senior and her mother appeared for an immigration check-in in San Antonio. The visit was described as routine. They expected to comply and leave.

Instead, ice officers detained both of them, placing them into immigration custody. The story described fear and uncertainty, along with disruption to school and family life. It also drew criticism from advocates and attorneys who argue that enforcement at scheduled appointments feels like a bait-and-switch.

Important limits on what can be confirmed from the available summary: the reporting referenced in the draft does not provide a specific incident date here. It also does not provide full biographical details that would allow readers to assess the family’s exact legal posture. Those missing facts matter because the legal options after an ICE detention often turn on case posture.

2) People involved (and why their roles matter)

The people described are a high school senior and her mother. The details shared publicly emphasize community ties and the student’s connection to school and future plans. Those facts can matter in several ways, though they never guarantee release.

advocates and immigration attorneys often become central after a check-in detention because they can act quickly on parallel tracks.

- Custody triage. Locating the detained person, identifying the ICE office, and confirming the detention basis.

- Case triage. Determining whether there is a prior removal order, a pending immigration court case, or a prior missed hearing.

- Strategy. Requesting prosecutorial discretion, pursuing bond where available, or filing emergency motions when deadlines are short.

- Evidence building. Gathering school records, proof of residence, and family ties that may be relevant to custody decisions.

Community ties like school enrollment can be relevant to “flight risk” arguments in bond contexts. But bond authority depends on the detention statute and the person’s history. See generally INA § 236 (arrest and detention); INA § 241 (post-order detention). Bond eligibility can also depend on criminal history and other bars.

3) Context and controversy: when check-ins become enforcement actions

What ICE check-ins are for

An ICE immigration check-in is usually a compliance event under ICE supervision. Some people are on an order of supervision after release from custody. Others are reporting while their cases move through court. Some are reporting while trying to reopen an old order.

ICE uses check-ins to confirm identity, address, and compliance. ICE may also review whether a person should remain at liberty or be detained. That authority is broad under INA § 236 and INA § 241, depending on whether the person has a final order.

Why the practice is controversial

Advocates often criticize enforcement at scheduled appointments for a practical reason: people show up voluntarily. They may bring children. They may come from work or school. If detention happens without warning, families can lose access to medication, phones, school pickup plans, and childcare arrangements.

ICE, for its part, has long asserted that enforcement decisions reflect priorities, legal posture, and compliance history. Outcomes can vary sharply. Two people with similar family circumstances may face different custody decisions because their cases are in different procedural stages.

What often happens immediately after a check-in detention

In many cases, the first hours focus on logistics. Families try to confirm where the person is held. Attorneys try to identify whether the person is in ICE custody at a local facility or transferred.

The next steps typically depend on whether ICE believes the person is removable, whether there is a final order, and whether the person may seek bond or other relief. The timeline of events can move quickly, especially if ICE treats the person as subject to expedited removal or reinstatement. Those pathways have separate rules and can narrow relief options. See INA § 235 (expedited removal) and INA § 241(a)(5) (reinstatement).

4) Distinction from the separate Austin case (avoid confusion)

Readers may be seeing multiple Texas stories at once. The San Antonio check-in detention is separate from an Austin incident involving a 5-year-old U.S. citizen and her mother.

The key distinction is the trigger:

- San Antonio: detention reported after a scheduled ICE check-in, where the family appeared as instructed.

- Austin: detention described as following police contact during a disturbance call, where an ICE administrative warrant surfaced and the family was transferred to ICE.

These differences matter because they involve different immediate response steps. A check-in detention often starts with ICE supervision paperwork and reporting requirements. A police-initiated transfer often involves local custody procedures, detainers, and different records requests.

Also, an ICE administrative warrant is not the same as a judicial arrest warrant signed by a judge. That distinction can affect how advocates assess local law enforcement policies and constitutional issues. It may also affect what records exist and where.

5) Public and legal implications: rights, schools, and community impact

Rights questions raised by check-in detentions

Detention at a check-in commonly raises questions like these:

- Can I call my attorney and family? In practice, access may depend on facility rules and timing. Attorneys can often enter appearances and request calls, but delays are common.

- Do I have the right to a lawyer? You generally have the right to be represented at your own expense in immigration proceedings. See INA § 292. There is usually no free appointed counsel.

- Do I have to answer questions? You can generally decline to answer questions beyond identity and basic biographical details. Silence can be protective when answers could be used against you.

- Will I see a judge? That depends. Some people are placed in immigration court proceedings. Others may be processed under different authorities.

If ICE initiates removal proceedings, the government typically serves a Notice to Appear (NTA) listing allegations and charges. See INA § 239. Procedural due process applies in removal proceedings. The Supreme Court has recognized that noncitizens in removal proceedings are entitled to due process. See Reno v. Flores, 507 U.S. 292 (1993).

School impacts when a student is detained

When a student is detained, families often face immediate school-related problems such as attendance and missed coursework. Access to transcripts and enrollment documents can be disrupted, and families may need to coordinate with counselors and administrators.

Privacy concerns arise when explaining an absence. Schools may request documentation. Families may worry about who can be told. While schools have obligations under student privacy rules, families should still be cautious about sharing sensitive immigration details. An attorney can help frame what is necessary and what is not.

How advocates and attorneys may intervene

After a high-profile check-in detention, lawyers and community groups may pursue multiple approaches:

- Requests for ICE review or discretion.

- Bond advocacy where bond is available.

- Motions in immigration court, including emergency filings if deadlines are near.

- Coordination with school officials for records and support letters.

None of these steps guarantees a particular result. But quick, organized action often helps preserve options.

Warning: Do not assume that showing up to an ICE check-in guarantees you will be released the same day. Detention decisions can change based on paperwork, prior orders, or enforcement priorities.

6) What readers might want to know next: practical protections and options

Your options depend on procedural posture. Two people can attend the same ICE office and face different outcomes because their cases differ.

– Pending immigration court case: the person may be eligible to seek bond and continue fighting the case in court. See INA § 236(a).

– Final removal order: ICE may treat the person as subject to removal under INA § 241, which can limit bond options and speed up transfer decisions.

– Old in absentia order: there may be a motion to reopen, but deadlines and exceptions are technical. See INA § 240(b)(5) and 8 C.F.R. § 1003.23.

– Possible reinstatement: prior removal can trigger reinstatement under INA § 241(a)(5), which changes the relief analysis.

Because these categories are technical, families often lose time by guessing. A lawyer can usually identify posture quickly by pulling the immigration court history and reviewing ICE paperwork.

Questions to raise with counsel immediately

If someone is detained at a San Antonio immigration check-in, families and supporters usually want answers fast.

- Where is the person being held, and under whose custody?

- What is the stated legal basis for detention?

- Is there a final order, and if so, from when?

- Is bond available, and where would bond be requested?

- Are there upcoming hearing dates or check-in dates that now change?

- What documents should be gathered right away?

Documentation and communication matter because facilities change. Files get misplaced. Deadlines can start running even while the family is still locating the person.

Deadline Alert: Motions to reopen and stays of removal can involve short, fact-specific timing rules. Speak with an immigration attorney as soon as possible if a final order may exist.

Practical steps families often take in the first 24–72 hours typically include confirming custody location, getting the A-number, collecting key identity and court documents, notifying schools or employers as needed, and coordinating with a licensed attorney for filings and contact with ICE.

Warning: Do not sign documents you do not understand in detention. Some signatures can waive hearings or speed removal.

7) Notes on data availability (what’s known vs. unconfirmed)

Public attention can help families. It can also spread confusion. In the San Antonio case described in the draft, key details are not provided here, including the specific incident date and complete biographical background. The teen is described as a high school senior, but her precise age is not included in the summary. The 5-year-old’s age belongs to the separate Austin matter.

Readers should be cautious about drawing conclusions from incomplete facts. ICE decisions often turn on documents not visible to the public, such as prior hearing notices, old orders, or internal custody determinations. If you are assessing your own risk for a check-in, rely on your paperwork and a lawyer’s review, not social media summaries.

Warning: Avoid sharing copies of NTAs, orders, or A-numbers publicly. That information can be misused and may affect privacy and safety.

What to do if you believe your rights were violated

If you believe ICE or another agency violated your rights during a check-in or detention, consider these steps:

- Write down the timeline while memories are fresh. Include names, badge numbers if known, and locations.

- Preserve documents. Keep copies of any papers you were given, even if you disagreed with them.

- Contact a qualified immigration attorney. Ask about custody review, bond, and any available complaints.

- If appropriate, consider reporting concerns to the DHS Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties (CRCL) or the ICE Office of Professional Responsibility (OPR) through official DHS channels.

For basic court information, EOIR provides case and court resources at EOIR (Immigration Court) information. For USCIS benefits information, see USCIS (immigration benefits).

Resources for legal help

– AILA Lawyer Referral: AILA Lawyer Referral

– EOIR (Immigration Court) information: EOIR (Immigration Court) information

– USCIS (immigration benefits): USCIS (immigration benefits)

Legal Disclaimer: This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.

This report examines the detention of a Texas student and her mother during an ICE check-in in San Antonio. It outlines the legal rights of noncitizens, the role of legal counsel, and the controversy surrounding enforcement at scheduled appointments. It also clarifies the distinction between check-in detentions and police-initiated transfers seen in other Texas cities, emphasizing the importance of understanding one’s procedural posture.