(SWEDEN) — Sweden’s government rolled out sweeping migration reforms this month and drew protesters into the streets, with critics warning that tighter return rules and retroactive changes are pushing long-settled workers and families toward deportation.

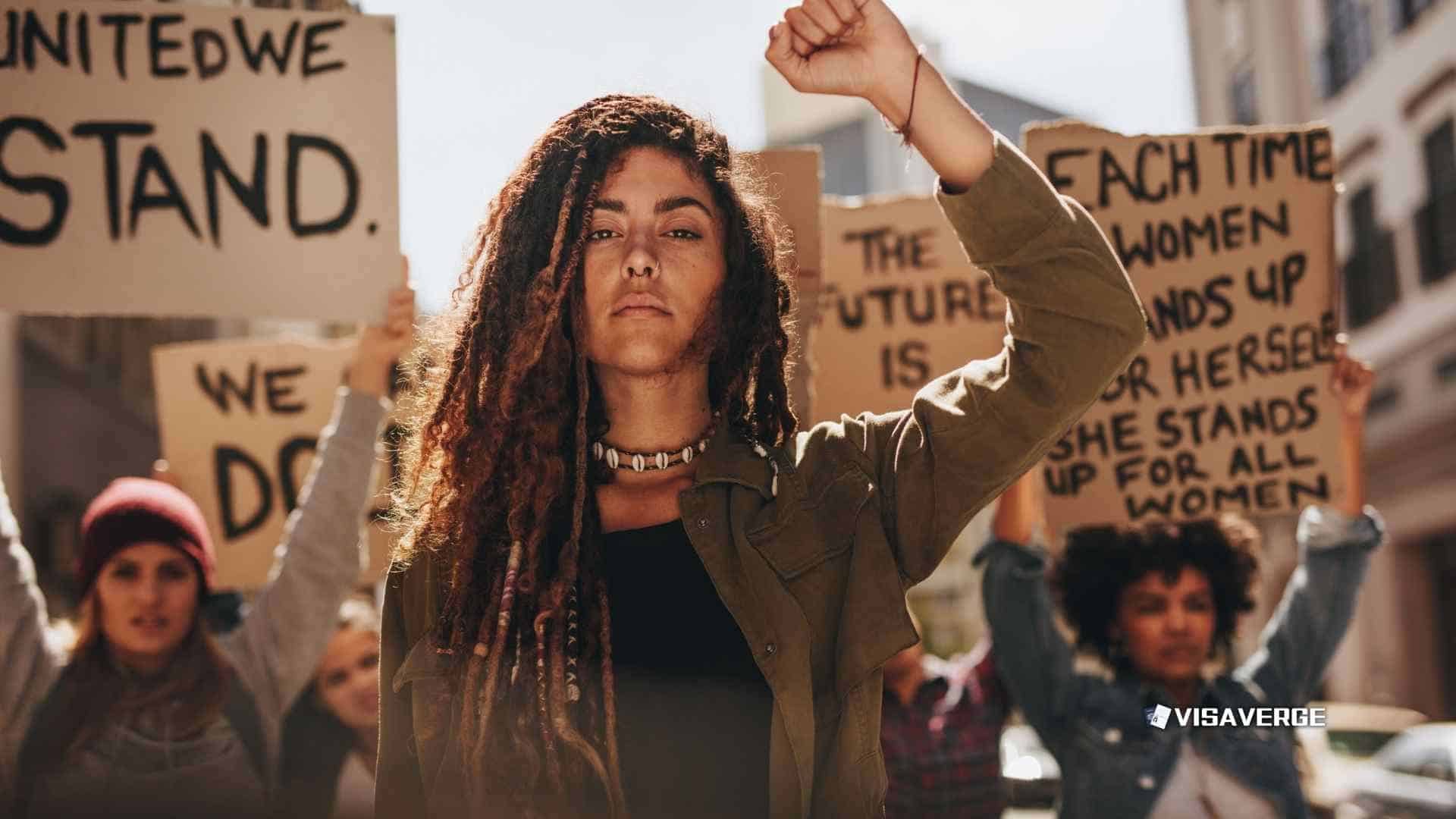

Demonstrations broke out across major cities including Stockholm and Umeå as the reforms entered what officials described as a critical implementation phase, placing the government’s promised “paradigm shift” in migration policy under a brighter spotlight.

Protests and public reaction

On January 3, 2026, roughly 1,000 protesters gathered at Sergels Torg in Stockholm, organized by groups including “Stop the Deportations” (Stoppa utvisningarna). Protesters argued that the government is “changing the rules of the game” for people who have lived and worked in Sweden legally for years.

Organizers and demonstrators pointed to:

– The perceived retroactive effect of some measures.

– The risk that well-integrated workers and their families could face deportation.

– Specific concern about employees in critical sectors like healthcare and elderly care.

Government rationale and official statements

Minister for Migration Johan Forssell framed the measures as necessary to ensure return decisions are enforced.

“The measures are to ensure that people who receive expulsion orders also leave the country” and to maintain “confidence in our migration system,” he said on January 1, 2026.

Forssell defended ending a pathway that allowed some rejected asylum seekers to remain by switching to a work permit from inside Sweden. He said:

– “‘Changing track’, which has undermined regulated immigration, will be abolished.”

– He described the increased financial support (repatriation grants) as something that “gives people more control over their choice to move.”

Director-General Maria Mindhammar emphasized voluntary return and procedural changes at the Swedish Migration Agency (Migrationsverket):

– “The aim is to make it easier for those who want to start over in their home country or another country.”

– “The Agency is stepping up its efforts to establish a well-functioning and legally secure process for applications,” she said on January 1, 2026.

What the reform package contains

Major elements of the reform package include:

- Sharply increased repatriation grants

- Abolition of “track change” (Spårbyte) — the legal route allowing rejected asylum seekers to apply for work permits from inside Sweden

- Higher salary thresholds for work permits

- Proposals related to the revocation of permanent residence permits for refugees

These measures together form what the government describes as a move toward one of the most restrictive migration frameworks in the EU.

Key policy changes (summary table)

| Policy change | Effect / detail |

|---|---|

| Repatriation grant increase (from Jan 1, 2026) | SEK 350,000 (~$34,000) per adult — up sharply from previous maximum of approx $1,000 |

| End of “track change” (Spårbyte) | Repeal took effect April 1, 2025; full impact being felt in early 2026 |

| Work permit salary threshold | Now requires at least 90% of the median wage (median listed as approx SEK 33,390) |

| Proposal to revoke permanent refugee permits | Refugees would need to reapply for temporary permits or citizenship by December 31, 2026; estimated 185,000 people could be affected |

Voluntary return incentive

A central new lever is the expanded financial incentive for voluntary return:

- As of January 1, 2026, the repatriation grant for voluntary return was raised to SEK 350,000 (roughly $34,000) per adult.

- This represents a dramatic rise from the previous maximum of about $1,000.

The Swedish Migration Agency and government present this as a way to make returns easier and to offer people agency in their decision to leave.

Enforcement, labor market impact, and numbers at risk

- Estimates vary, but 600 to 2,600 well-integrated workers are now said to be at risk of deportation due to the track change repeal.

- Reported at-risk workers include staff in healthcare and elderly care.

- Critics say enforcement is now colliding with workplaces and communities that have relied on these workers.

Sweden Democrats migration spokesperson Ludvig Aspling defended the reforms:

– “Sweden has had lax rules on returns for decades and this is an important step towards changing that.”

Proposed revocation of permanent residence for refugees

A separate government inquiry has proposed general revocation of permanent residence permits for refugees:

– Under the proposal, affected refugees would have to apply for temporary permits or citizenship by December 31, 2026.

– News reports estimate about 185,000 people could be affected, fuelling anxiety among those who believed their status was settled.

International echoes and parallel U.S. moves

The Swedish reforms have drawn international attention for rhetorical and policy parallels with a so-called “remigration” agenda in the United States.

- On October 14, 2025, a U.S. Department of Homeland Security official X account posted a single-word message: “Remigrate.”

- The term is widely used in European far-right circles to describe mass return of migrants.

- The DHS post was later linked to a State Department proposal to create an “Office of Remigration” to facilitate voluntary and forced returns.

On the same day Sweden launched several key measures, U.S. immigration authorities made procedural changes:

- USCIS Policy Memorandum PM-602-0194 (dated January 1, 2026) instituted an immediate “hold and review” for applications from an expanded list of “high-risk” countries.

- In a USCIS News Release dated November 13, 2025, Director Joseph Edlow said the agency had taken “critical steps to restore sanity and integrity to our immigration system” by closing “loopholes” and referring thousands with removal orders to ICE.

Observers note how language and policy on returns can travel across borders, with both Swedish and U.S. agencies adopting sharper messaging and new adjudication steps meant to tighten screening and enforcement.

Implementation tensions and contested narratives

The reforms pair stronger enforcement with incentives for voluntary return:

– The government presents the increased repatriation grant as a support mechanism for those who choose to leave.

– Simultaneously, ending legal pathways such as track change restricts routes that previously allowed some people to shift into work-based status.

This has produced two competing narratives:

– Government: emphasis on rule enforcement, restoring confidence, and regulated immigration.

– Protesters and organizers: claims that the government is changing long-standing expectations for those who have built lives in Sweden and filled critical jobs.

Broader significance

As implementation continues, the reforms are increasingly described as:

– A Swedish test case for hardline migration policy within the EU.

– Part of a wider debate about “remigration” that has surfaced in some official U.S. messaging.

Minister Forssell’s stated goal remains:

“Ensure that people who receive expulsion orders also leave the country.”

Sweden’s government launched restrictive migration reforms in early 2026, sparking protests in Stockholm. The package includes raising repatriation grants to $34,000, ending ‘track change’ work permit routes, and proposing the revocation of permanent residence for refugees. While officials claim these steps ensure system confidence and legal enforcement, critics warn that up to 2,600 integrated workers, particularly in healthcare, now face deportation risks as the rules change retroactively.