Polish authorities have moved to strip international protection from Russians at far higher rates than any other group, making them the most frequent targets of revocation in recent years. Nearly 90% of all foreigners who lost asylum status in Poland during that period were Russian citizens, according to case figures reviewed by advocacy lawyers and cited in court filings. The trend has become more visible as removals from the country rise and as decisions by top courts lock in stricter readings of the law.

Grants versus revocations: a stark contrast

The pattern runs alongside contrasting numbers on grants. In 2024, Polish authorities recognized 119 Russian citizens as refugees. At the same time, Russians faced the highest rates of protection cessation among all nationalities, underscoring how fragile asylum status can be for those who fled Russia and later tried to manage documents or family ties across borders.

For Russian applicants, that mix of approvals and revocations in Poland shows both a door that is still open and a higher risk of losing status after entry.

Rising enforcement and its implications

Enforcement has picked up pace. In the first two months of 2025, over 1,300 people were deported from Poland—almost double the roughly 700 removals recorded in the same period a year earlier. Not all deportations involve asylum seekers, but the spike signals a harder line in the handling of foreigners overall and sets the backdrop for the growing share of Russians who lose protection.

- Lawyers working with protection holders now warn clients that simple life events—like renewing a passport—can trigger fresh scrutiny.

- A harsher enforcement climate shortens the time window for appeals and increases the pressure on those whose statuses are revoked.

Most frequent triggers for status loss

The most common reasons Polish authorities cite when revoking protection for Russians include:

- Return travel to Russia after protection is granted, which authorities treat as evidence that the person no longer fears persecution or serious harm.

- Obtaining or renewing Russian passports, especially biometric passports, which authorities interpret as direct contact with Russian state services.

- Changed conditions in regions such as the North Caucasus (notably Chechnya), where officials have sometimes concluded that security has improved since the applicant’s arrival.

Human rights groups emphasize that many of these activities are practical necessities—caring for an ill parent, selling property, collecting records, or renewing documents for children or work.

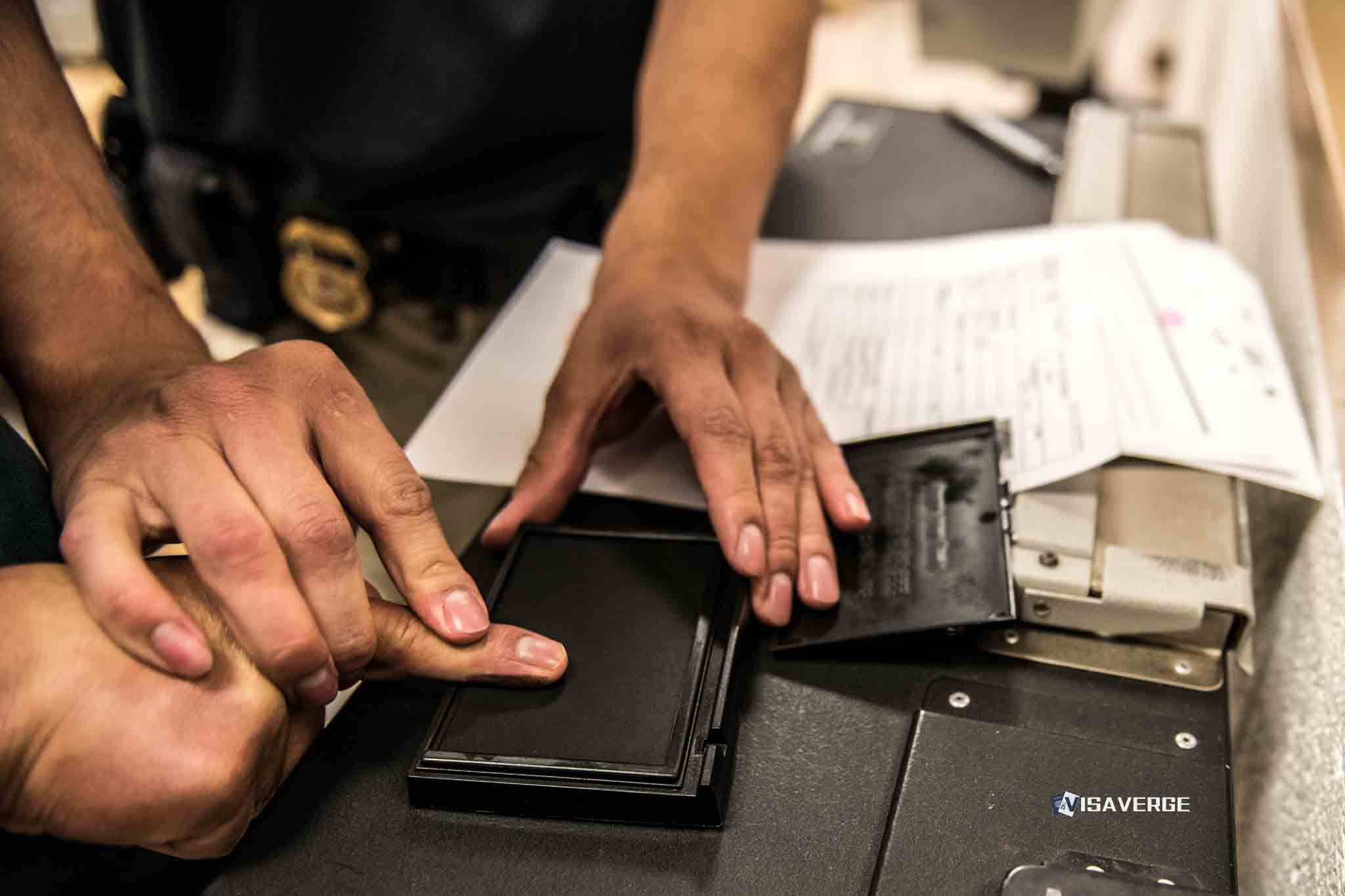

Courts and biometric evidence

Court rulings have reinforced the authorities’ stance on biometric passports and travel.

- In a 2022 case, the Supreme Administrative Court upheld revocation where a Russian man argued he did not personally collect a passport. Judges pointed to the biometric process (which requires fingerprints) and accepted that the document could not be obtained without the holder’s direct interaction.

- In another case, a Russian family of five lost subsidiary protection after officials learned passports were issued while they were in Belarus. The court concluded that passport acquisition indicated renewed ties with the Russian state and weakened claims of risk.

Courts have tended to treat biometric passport issuance as a clear and difficult-to-rebut marker of personal contact with Russian authorities.

Lawyers say this emphasis on biometrics makes it hard to counter revocation claims with witness statements or assertions that an intermediary acted on the applicant’s behalf.

Disputed approach to changed country conditions

Polish officials have ended subsidiary protection for some Russians by asserting that the situation in the North Caucasus has improved since their arrival.

- Decision-makers argue that an improved security environment undermines the basis for protection.

- Human rights organizations counter that this generalized approach can miss individual circumstances, such as ongoing pressure, surveillance, or threats linked to family, local authorities, or political activity.

These groups warn that headline improvements do not always reflect specific risks faced by particular people.

Political context and guidance to local offices

The political climate in Poland supports tougher control. Both the ruling camp and many opposition figures have backed a firmer line toward Russian nationals since the invasion of Ukraine and amid wider regional tension.

- This cross-spectrum consensus has shaped guidance to local offices.

- The message sent: return travel, contact with Russian offices, and passport renewals will draw attention.

As a result, lawyers report that clients now receive early warnings about actions that could trigger scrutiny, yet families still face difficult choices—such as whether to travel to care for a sick relative or to renew a child’s documents for school.

Everyday dilemmas for those with protection

For people living with protection in Poland, practical needs often conflict with the risk of revocation.

- Russians frequently need valid documents to work, rent housing, or register births and marriages.

- Seeking those documents can expose them to the very findings that cost them asylum status.

- Some attempt to use intermediaries or third countries, but authorities have sometimes counted a biometric passport issued in their name as evidence of personal contact with Russian authorities.

- Others choose to let documents expire, risking fines and barriers to everyday life.

Deportation pressure and appeals

Deportation data adds urgency for those who lose status. With removals running higher in early 2025, people who face revocation may have a shorter runway to challenge decisions before being asked to leave.

- Appeals are possible, but courts have shown a tendency to interpret evidence narrowly against applicants.

- The emphasis on biometric markers gives authorities a straightforward evidentiary basis that is difficult to attack.

Legal framework and official guidance

Poland’s legal framework allows authorities to end protection when:

- Someone re-avails themselves of their home country’s services, or

- The original reasons for protection no longer exist.

Official guidance on cessation and withdrawal is published by the Office for Foreigners, which explains eligibility, procedures, and grounds used by decision-makers. Readers can find general information on international protection on the Polish government’s Office for Foreigners website at the Office for Foreigners. That site outlines steps in asylum processing and references the legal standards used in revocation.

Human impact

Community groups report growing human costs:

- Families who have lived in Poland for years face sudden uncertainty when a parent’s status is canceled and children’s residency hinges on that parent.

- Workers who expected stability find themselves fighting to stay while employers hesitate to renew contracts.

- Caseworkers in border regions and cities report more Russians asking whether a one-time trip to settle family affairs could end their stay.

What the current pattern means going forward

Even with firmer policy, the 2024 approvals show that Poland still grants protection to Russians who can demonstrate current, personal risk. However, the split between new grants and rising revocations suggests:

- The system is sorting cases more aggressively after status is issued.

- Any post-recognition contact with Russia—travel, passports, or other visible ties—is likely to be weighed heavily against the person.

Lawyers expect more court disputes in 2025 over:

- What legally counts as “contact” with Russian authorities.

- How to measure changes in risk levels in places such as Chechnya.

For now, the rules already applied—travel, passports, and a sharper reading of risk—have turned routine life events into potential turning points for people who believed they had found safety in Poland.

This Article in a Nutshell

Poland has revoked asylum protection for Russians at disproportionately high rates—nearly 90% of recent cessations—while still granting 119 refugee statuses in 2024. Revocations have increased amid firmer enforcement, with over 1,300 deportations in early 2025. Authorities cite return travel, biometric passport issuance, and improved conditions in regions like Chechnya as common triggers. Courts have upheld strict readings of biometric evidence. Lawyers and NGOs warn that routine actions can prompt revocation and that appeal windows are narrowing.