- ICE agents defied a federal court order by transferring a toddler to Texas hours after her detention.

- The operation led to multiple child detentions in Minnesota, sparking intense legal and political scrutiny.

- A 2-year-old girl was eventually reunited with her mother after a frantic legal battle over jurisdiction.

MINNEAPOLIS, MINNESOTA — ICE detained a 2-year-old girl from Ecuador and her father during a traffic stop in Minneapolis on Thursday, January 22, 2026, then flew them to Texas hours later despite a federal judge’s emergency order barring an out-of-state transfer.

Attorneys filed an emergency habeas petition within five hours of the detention and secured a court order by 8:10 p.m. Thursday to block DHS from moving the pair out of Minnesota. Court documents said DHS placed them on a plane to Texas 20 minutes later anyway, prompting a second order requiring the child’s release.

The judge’s initial emergency order prohibited the transfer out of Minnesota and required the child’s release by 9:30 p.m. Friday, January 23. The rapid sequence of filings, orders and the commercial flight became central to the legal dispute over jurisdiction and custody.

Lawyers involved in the case say swift interstate transfers can make it harder for families to reach counsel, for attorneys to appear in the right courts on short notice, and for relatives to reunify quickly when children end up in separate custody channels. Even short moves across state lines can shift where court actions land and who can respond in time.

DHS said the family entered the U.S. at a port of entry using the CBP One app to seek asylum and had an active asylum claim when ICE detained them. DHS said officers took the father into custody after citing him for erratic driving with the child in the vehicle and for prior felony reentry.

The department also said agents attempted to release the child to her mother nearby, but the mother refused. Attorneys and advocates have treated the competing accounts of what happened next as central to the court fight over whether the child should have remained in Minnesota and who had authority to take custody.

After the transfer to Texas, the child later returned to Minnesota and reunited with her mother. The attorney in the case obtained parental authority to retrieve her from detention, and the child has since been safely reunited with her mother in Minnesota.

The Minneapolis detention came amid ICE’s Operation Metro Surge in Minnesota, an effort that has drawn scrutiny from school officials, immigration lawyers and some federal judges after reports that agents detained multiple children during the month. Advocates have highlighted how quickly some families moved from Minnesota to Texas, saying the speed of transfers can outpace efforts to file emergency challenges.

Reports from the month described ICE detaining at least nine children, including the 2-year-old girl from Ecuador and several older children. Among those cases, advocates have focused on a 5-year-old Ecuadorian boy, Liam Conejo Ramos, whose detention became a flashpoint for debate over how agents handle arrests of parents with children present.

In Liam’s case, his father, Adrian Alexander Conejo Arias, was detained after fleeing on foot in a driveway. School officials said Liam’s mother was home and begged for the boy, while Marcos Charles, the top ICE official in Minneapolis, accused the father of “abandoning his child in the middle of winter,” and said an officer stayed with the child while pursuing the father.

Columbia Heights Public Schools Superintendent Zena Stenvik said ICE used the 5-year-old “as bait” by leading him to the door to knock. The statement added to criticism from educators and community members who say school staff and families ended up scrambling to verify where a child was taken and who could retrieve him.

Vice President JD Vance defended agents involved in the 5-year-old’s case, framing the decision as a matter of immediate safety.

“What are they supposed to do? Let a 5-year-old freeze to death?”

Other reported detentions during the month included a 10-year-old whose mother was detained en route to work in Hopkins, and a 12-year-old from Venezuela whose family of six was detained at home. Those accounts, alongside the 2-year-old’s rapid transfer, sharpened concerns among lawyers that parents could lose access to their children while trying to respond to fast-moving enforcement actions.

Immigration attorney Mark Prokosch, who also represents Liam’s family, criticized the detention of children in ICE operations and said authorities lacked a legal basis for doing so in the circumstances described in the cases.

“unspeakable, cruel and without any legal basis,”

Prokosch called child detentions “unspeakable, cruel and without any legal basis,” and said families “did everything right” by using the app, scheduling appointments, and presenting at the border.

The 2-year-old’s case drew immediate legal scrutiny because a federal judge intervened quickly and issued a written order aimed at freezing custody and keeping the child in Minnesota. Attorneys pointed to the narrow window between the 8:10 p.m. order and the flight described in court documents, arguing that the speed of the transfer effectively prevented the court from enforcing its directives before the child crossed state lines.

DHS defended its custody and transfer practices more broadly, saying decisions about where to hold detainees depend on bed space. DHS also said detainees have phone access to families and lawyers and receive lists of free or low-cost attorneys, a response aimed at countering claims that families become unreachable after transfers.

Attorneys involved in the cases, including Callan Gray, have argued that even when contact is technically available, interstate moves can make it harder to secure representation in time for emergency court actions. Lawyers also say that when a family’s community ties, school contacts and local advocates sit in Minnesota, moving a parent or child to Texas can slow communication during the most time-sensitive phase of a case.

The reported transfers to Texas have put added attention on the practical effect of moving parents and children away from the courts and lawyers who can respond fastest in Minnesota. Immigration detention often requires rapid coordination among counsel, relatives and local support networks, and attorneys say a move across multiple states can fracture that coordination even when phone calls remain possible.

In the 2-year-old’s case, the legal fight centered on the child’s physical location and custody status during the hours after the traffic stop. Attorneys acted quickly with an emergency habeas petition within five hours of detention, and the court issued a transfer-blocking order the same day, only to have the pair placed on a flight soon afterward, according to court documents.

The child’s reunification with her mother in Minnesota marked a different outcome than what attorneys feared in the hours after the transfer, when they argued the move could lead to prolonged separation. The attorney’s receipt of parental authority to retrieve the child became a key step in bringing the child back into her mother’s care.

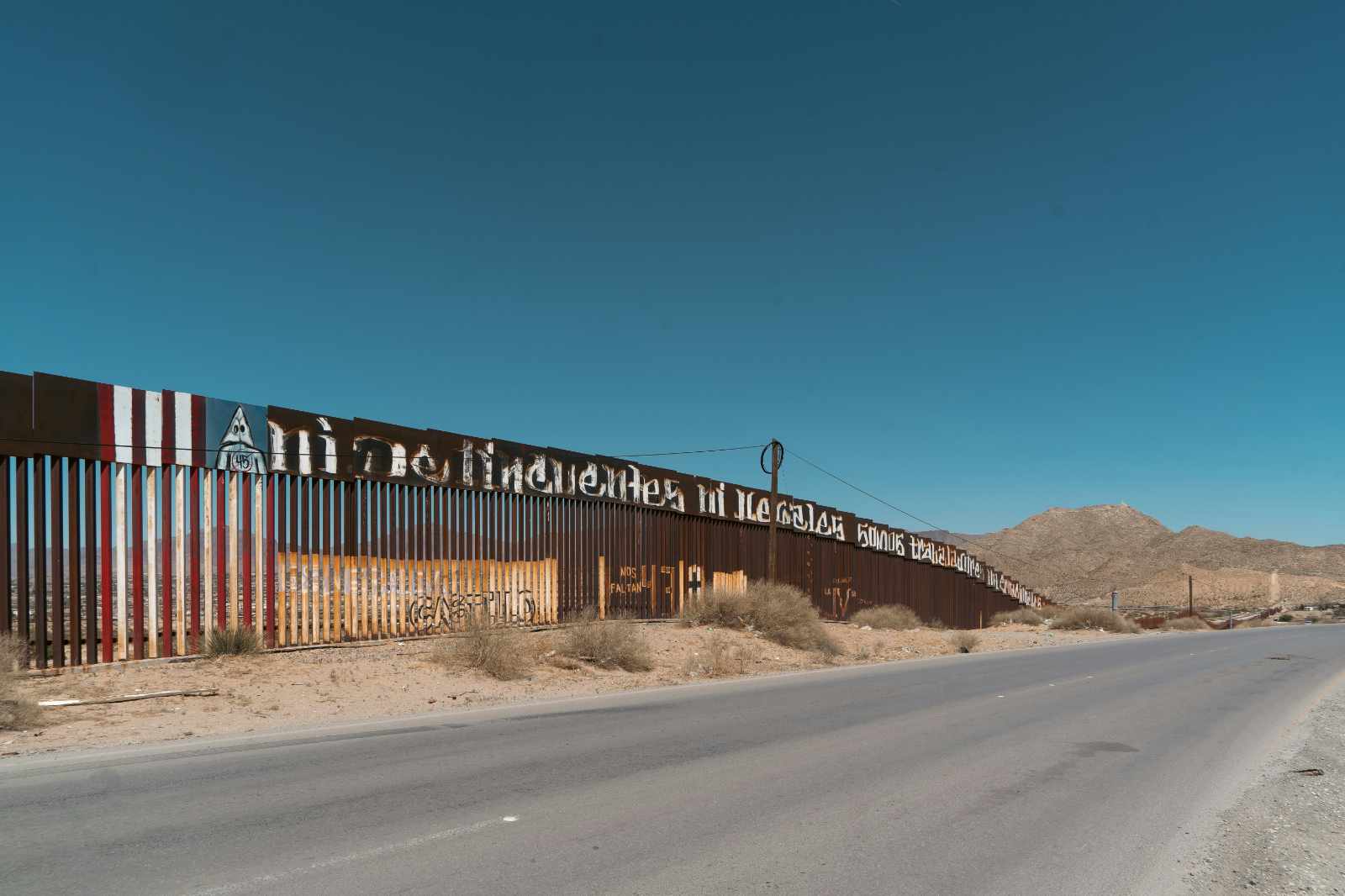

Liam and his father remain in Texas, held at Dilley Immigration Processing Center, an hour south of San Antonio. The location has become a focal point for advocates who say Texas detention complicates family contact for people whose lives, schools and legal help remain rooted in Minnesota.

Federal judges have ordered DHS to return several such children and parents to Minnesota after swift Texas transfers. Those rulings have underscored the role of federal courts in reviewing fast-moving enforcement actions, particularly when attorneys argue that a transfer undermines access to counsel or interferes with a court’s ability to preserve the status quo while it reviews a child-custody dispute.

The series of cases has also intensified public debate in Minnesota over how immigration enforcement intersects with local institutions such as schools and with families who used the CBP One app as they sought asylum. Prokosch’s comments tied that point directly to the families he represents, saying they “did everything right” by using the app, scheduling appointments, and presenting at the border.

For DHS, the defense has emphasized operational constraints, including bed space and the need to manage detention placements, while maintaining that detainees can contact lawyers and family members and can access lists of free or low-cost attorneys. Attorneys and school officials, in turn, have focused on how quickly events unfold once ICE takes a parent into custody, particularly when young children are present and decisions about release or placement must happen in minutes.

The dispute over what occurred in the 2-year-old’s traffic-stop detention has hinged on DHS’s account that agents attempted to release the child to her mother nearby and that the mother refused, while attorneys treated the court filings and the child’s movement as evidence that the family lost meaningful control over custody in the crucial hours after the stop. In the Liam case, the clash has centered on whether the father abandoned the child, as Charles alleged, or whether the child could have remained with his mother, as school officials maintained.

As court actions continue in multiple cases tied to Operation Metro Surge, lawyers have kept attention on the timelines of detention, the speed of interstate transfers to Texas, and how those moves shape the next hearings. The disputes have also sharpened the stakes for families trying to stay in contact with children during enforcement actions that, as Vance put it, raise urgent questions about what officers should do in the moment:

“What are they supposed to do? Let a 5-year-old freeze to death?”