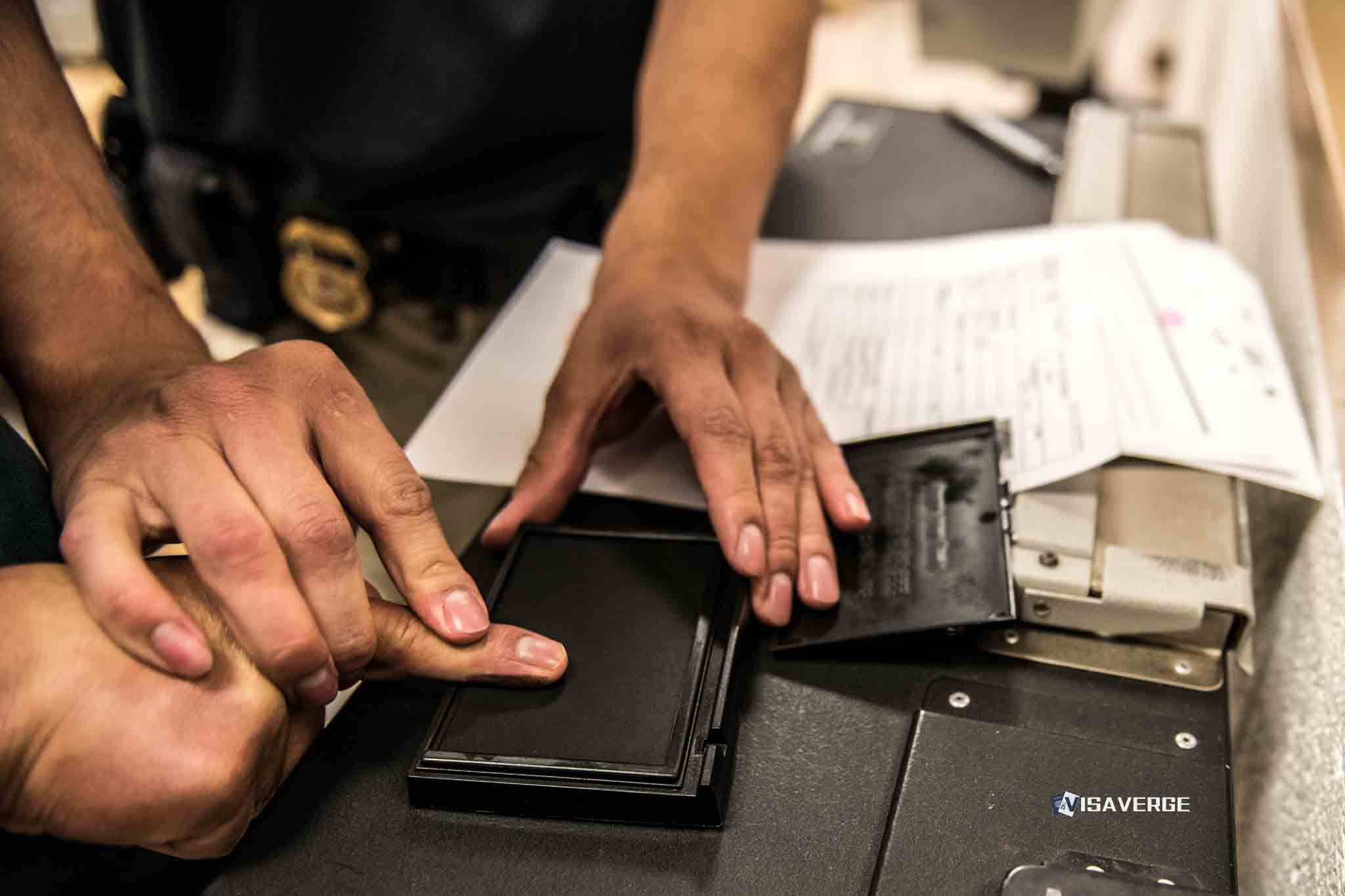

(FLORIDA) — A key Board of Immigration Appeals decision, Matter of Guerra, 24 I&N Dec. 37 (BIA 2006), holds that immigration judges deciding release on bond must weigh specific public-safety and flight-risk factors, and must set bond at an amount that reasonably assures court appearances. As Florida awaits federal approval for a third state-run immigration detention center—reportedly planned for the Florida Panhandle—the practical impact is immediate: more detained respondents may seek bond redeterminations, and Guerra remains the core framework that judges use to decide who can be released and on what conditions.

Governor Ron DeSantis said on January 5, 2026, that Florida is awaiting Department of Homeland Security (DHS) sign-off for the third facility. State officials say the existing network is designed to expand bed space and increase removals. For detained noncitizens, however, the legal questions are less political and more procedural. The first question is often whether a bond hearing is available at all. The second is how to win it.

The precedent: what “Matter of Guerra” requires in bond cases

Under INA § 236(a), many noncitizens in removal proceedings may be arrested and detained, but may also request release on bond or conditional parole. The custody process is implemented through DHS custody determinations and, for eligible respondents, immigration judge review under 8 C.F.R. § 1236.1(d).

In Matter of Guerra, 24 I&N Dec. 37 (BIA 2006), the BIA explained that bond is discretionary and fact-specific. The immigration judge should evaluate:

- whether the person is a danger to property or persons, and

- whether the person is likely to appear for future hearings.

The decision lists common considerations, including:

- Fixed address and community ties

- Employment history

- Family relationships and caregiving responsibilities

- Length of residence in the United States

- Past record of appearances in court

- Criminal history and rehabilitation evidence

- Prior immigration violations, including past removal orders

Guerra is frequently cited because it provides practitioners with a clear checklist. It also reinforces that bond is not a punishment mechanism: the amount must relate to the assessed risk and the record evidence.

Key facts behind the decision

Guerra arose from a custody dispute where the record included adverse factors that DHS argued justified continued detention. The BIA emphasized that the judge’s analysis must be individualized, rejecting a one-size-fits-all approach to bond amounts.

The decision also underscored that the respondent bears the burden to show that release would not create unacceptable risk.

Although Guerra predates today’s large-scale detention capacity debates, it remains the practical rulebook in everyday bond litigation, including cases arising from intensified local-federal enforcement cooperation.

Why this matters now: detention expansion and “front-end” procedure

Florida officials describe a pipeline that starts with arrests and funnels people to state-managed detention hubs. State officials have reported about 20,000 immigration-related arrests in 2025, with a large share tied to a state-federal initiative. They have also described a steady cadence of removal flights from North Florida.

As detention beds expand, the bond docket typically expands with it. That often produces three recurring procedural flashpoints:

- Eligibility for an immigration judge bond hearing

- The quality of the custody record and documentary proof

- Speed and access to counsel, especially for rural facilities

A new Florida Panhandle detention site could make attorney access harder for some families. It could also affect how quickly counsel can gather evidence for a bond packet. Geography often becomes a practical barrier even when the legal standard is clear.

Warning (Bond eligibility is not universal): Some people are held in mandatory detention and may be barred from bond under INA § 236(c). Others may be detained under post-order authority in INA § 241. Ask counsel which statute applies before preparing a bond case.

The threshold issue: when bond may be unavailable

Not every detained respondent can seek a Guerra-style bond hearing. The main exclusions are:

- Mandatory detention under INA § 236(c) for certain criminal or terrorism-related grounds.

- Arriving aliens, who generally have limited bond options in immigration court.

- Post-final-order detention under INA § 241, where custody review follows different rules.

In Matter of Joseph, 22 I&N Dec. 799 (BIA 1999), the BIA recognized a limited avenue to contest whether INA § 236(c) applies at all. These are often called “Joseph hearings.” The respondent must show that DHS is substantially unlikely to establish the charge triggering mandatory detention.

That distinction matters in Florida’s current moment. Public statements emphasize that a majority of arrestees allegedly have criminal histories. Criminal history does not always mean mandatory detention, but it often triggers DHS arguments for it.

Quick-reference table: common detention statutes and bond availability

| Detention authority | Typical bond availability | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| INA § 236(a) | Possible | Discretionary bond review by immigration judge under 8 C.F.R. § 1236.1(d) |

| INA § 236(c) | Typically not available | Mandatory detention for certain criminal/terrorism grounds; may be challenged via Joseph hearing |

| INA § 241 | Limited | Post-final-order detention; custody review follows different procedures |

How Guerra shapes the evidence in today’s bond hearings

Where bond is available, Guerra effectively rewards preparation and punishes gaps in proof. Immigration judges want corroboration, not mere assurances. Common and persuasive evidence includes:

- Lease, mortgage, utility bills, and a letter confirming a stable address

- Employer letter and recent pay stubs

- Proof of caregiving duties (medical records, school letters)

- Criminal court dispositions (not only arrest reports)

- Treatment completion records where relevant

- Letters from community members with specific facts (employment, relationships, reliability), not slogans

In a detention surge, judges may have less time per case. That increases the value of a well-organized written bond packet and raises the stakes of interpreter issues and missing documents.

Deadline (Move quickly after detention): Bond hearings can be scheduled on short notice. Families often lose time gathering certified dispositions. Start record requests immediately after arrest.

Potential friction points: prolonged detention litigation and circuit differences

Florida falls in the Eleventh Circuit, but national detention litigation still matters because many detainees file habeas corpus petitions in federal district court. The Supreme Court has limited court-imposed bond-hearing timelines in some contexts, and litigation over prolonged detention continues to vary by jurisdiction and posture.

Two practical points for Florida cases:

- The availability of immigration judge bond review depends first on the detention statute.

- Challenges to prolonged detention often depend on federal court precedent and case facts.

Because rules can differ across circuits, practitioners should not assume that arguments successful in the Ninth Circuit will work the same way in the Eleventh. Venue, custody statute, and procedural posture all matter.

Warning (Do not miss the right forum): Immigration judges decide bond only where regulations allow it. Federal courts may hear constitutional detention claims through habeas. A lawyer should assess the correct route early.

Conditions claims versus bond: related but different fights

Reports of litigation over conditions at existing Florida detention sites highlight a separate legal lane. Conditions claims may be brought in federal court and may seek injunctive relief. Those cases are distinct from an individual bond request.

Still, conditions can intersect with custody advocacy. In some cases, attorneys argue that unsafe conditions heighten due process concerns or justify expedited custody review. Results vary and are highly fact-specific.

No major dissents in Guerra, but a continuing tension in bond practice

Guerra itself is not remembered for a headline-grabbing dissent. Its significance is more durable: it institutionalized a factor-based approach that still governs bond decisions.

The continuing tension is between discretionary bond decision-making and the reality of high-volume detention systems. When capacity grows, consistency often becomes harder, which can lead to uneven bond amounts for similarly situated respondents.

Practical takeaways for detainees and families in Florida

- Identify the detention authority immediately. Ask whether DHS is detaining under INA § 236(a), INA § 236(c), or INA § 241.

- If bond is available, build a Guerra record. Bring documents showing stability, compliance, and rehabilitation.

- Get certified criminal dispositions. Arrest reports are not enough and may be misleading.

- Prepare a sponsor plan. A sponsor with lawful status, stable income, and transportation plans can help.

- Do not rely on politics as a legal argument. Judges decide custody on the record and statutory framework.

A new Panhandle facility may also affect logistics. Families should plan for travel, mail delays, and limited phone access. Counsel can request continuances or rescheduling in appropriate cases, but outcomes vary.

Strong attorney involvement is particularly important for anyone with arrests, prior removal orders, or pending asylum-related claims. Those issues can change detention authority and bond eligibility.

Official resources (government)

- EOIR Immigration Court information: EOIR Immigration Court information

- USCIS home (benefits and filings): USCIS home (benefits and filings)

- INA and regulations (Cornell LII): law.cornell.edu

Resources:

– AILA Lawyer Referral: AILA Lawyer Referral

⚖️ Legal Disclaimer: This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.

This article explores the legal precedent of Matter of Guerra within the context of Florida’s expanding immigration detention system. It details how immigration judges exercise discretion to grant bond based on public safety and court appearance history. While Florida adds more beds, the article clarifies that legal eligibility for bond varies by statute, emphasizing the necessity of thorough documentary evidence and timely legal counsel to navigate the system.