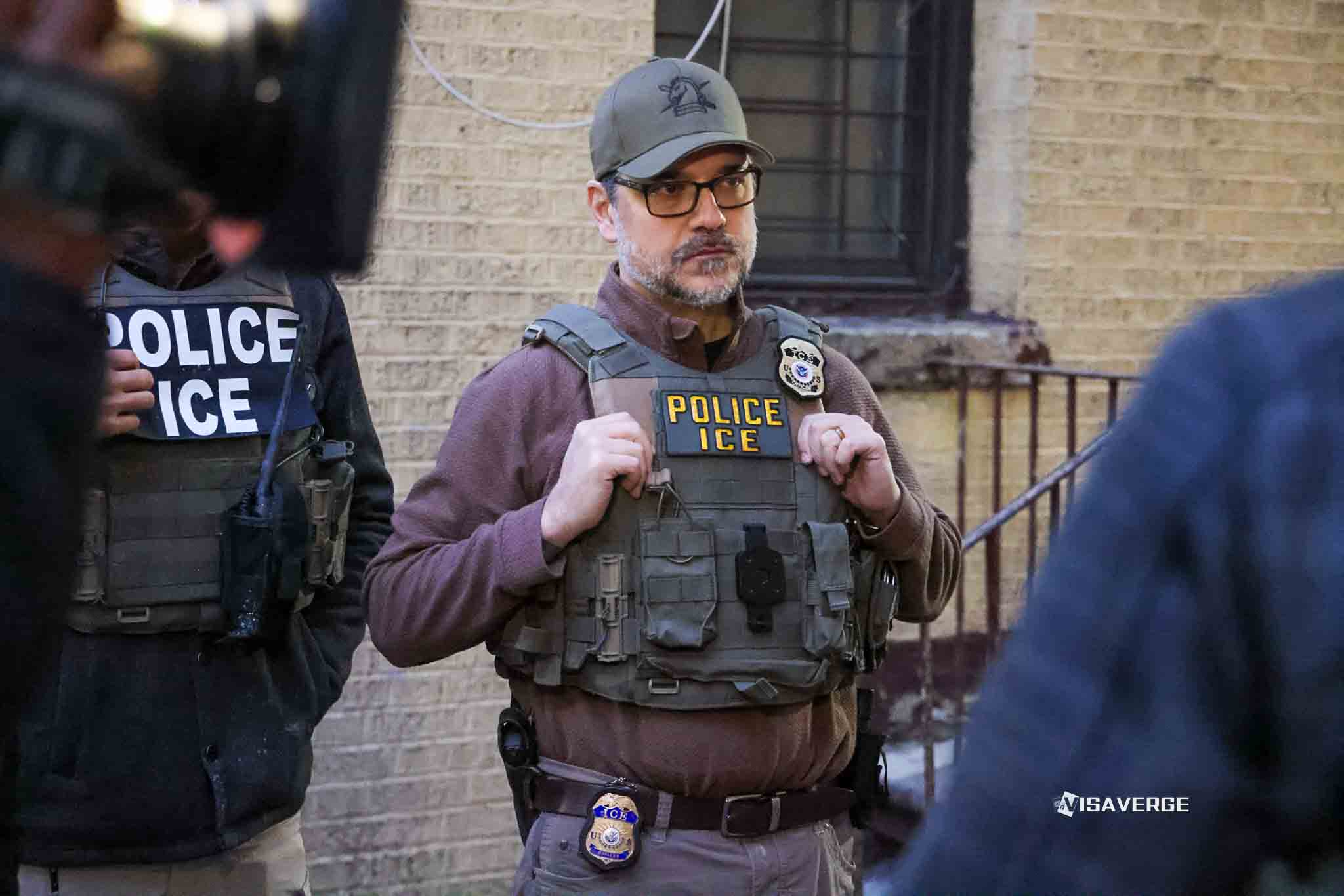

(BALTIMORE, MARYLAND) Federal purchasing records and a new county-federal agreement point to a marked expansion of ICE presence and enforcement activity in Baltimore and across Baltimore County heading into late 2025, with arrest totals already outpacing last year’s numbers and community groups reporting a climate of fear and economic strain. At the end of September, immigration authorities awarded a six-month supply contract for tens of thousands of shelf-stable meals in Baltimore and Salisbury, Maryland, and on October 31, 2025, county officials said Baltimore County is no longer a “sanctuary jurisdiction” after signing a memorandum of understanding with federal agencies that formalizes cooperation inside local jails.

The logistics deal, issued by ICE and the Department of Homeland Security, directs more than $233,000 to Kinro Manufacturing to provide 42,000 shelf-stable meals over six months in Baltimore and Salisbury. Though routine on paper, the size and duration of the order suggest preparations for sustained operations and a larger ICE footprint in central Maryland. Coupled with a jump in arrests and a new policy bridge between Baltimore County corrections and federal enforcement, the contracting move is fueling concern among immigrant advocates and small-business leaders that an expanded federal presence will ripple quickly through neighborhoods where residents already avoid daily routines for fear of detention.

The county’s memorandum of understanding, signed with DHS, ICE and the Baltimore field office of Enforcement and Removal Operations, commits local corrections officials to notify federal agents when inmates are the subject of immigration detainers or federal warrants and to tell ICE when those inmates are scheduled for release. Baltimore County officials framed the change as procedural alignment with other Maryland jurisdictions, and emphasized that the agreement does not alter how county corrections staff handle their work.

“This agreement makes no changes to the Department of Corrections’ standard practices and aligns Baltimore County with peer jurisdictions throughout the state of Maryland,” said Dakarai Turner, spokesperson for the county government.

State-level skepticism of deeper local-federal collaboration has colored immigration enforcement in Maryland for years, but the new Baltimore County agreement marked a public shift. Supporters of tighter coordination argued it would bolster safety by ensuring people sought by federal authorities are not released without notice.

“Despite restrictions from state leadership, Baltimore County has shown a willingness to cooperate with federal immigration enforcement. This is a small step toward restoring public safety and we appreciate the county’s commitment to updating its policies,” said Associate Attorney General Stanley Woodward.

The paperwork is landing amid a surge in enforcement. In the first seven months of 2025, ICE recorded 2,280 arrests within the Baltimore Area of Responsibility, which spans all of Maryland and parts of Virginia and Delaware. That total already eclipsed the 1,498 arrests logged in all of 2024. The majority of those arrested this year came from Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and Mexico, underscoring how stepped-up detention affects families whose ties stretch across Central America. The arrest data, together with the county’s MOU and recent federal contracts, has convinced many local organizers that Baltimore and Baltimore County should brace for intensified operations in the months ahead.

For immigrant families, advocates say the shift is already playing out in household decisions as basic as who does the school run and which stores to visit. Eric Lopez of the Amica Center described the current environment as

“profoundly chilling,”

a phrase he used while warning that more people picked up by enforcement teams are being “funneled into ICE custody” and face rising barriers to finding lawyers. Those barriers include language obstacles, limited access to counsel from detention, and higher costs associated with rapid timelines, according to service providers, who describe long days trying to field new calls while navigating families’ fears about the increased ICE presence around workplaces and traffic corridors.

The expansion is also hitting storefront economies that depend on steady foot traffic from Spanish-speaking communities. Johanna Barrantes, small business project manager at Southeast CDC, said the heavy ICE presence has produced a steep drop in revenues and customers for immigrant-owned shops, with some streets now described as “desolate” as families choose to stay home rather than risk a stop on the way to buy groceries or wire money.

“For many folks that are in these targeted communities, they are going to have to make, yet again, another really difficult choice: what’s more at risk? My financial resources or my physical safety?” Barrantes said.

Shopkeepers are reverting to pandemic-era tactics to survive, she added, including trimmed hours, delivery by trusted staff, and informal credit for longtime customers who cannot afford the trip during a week when enforcement feels especially visible.

Attorneys working in Baltimore’s immigration courts and detention dockets say a procedural shift is amplifying the impact: the expansion of expedited removal, a fast-track process that allows the government to quickly deport certain people without a hearing before an immigration judge. Adonia Simpson, a Baltimore-based immigration lawyer, said the policy is now being applied to people who have lived in the United States for years, rather than only to recent arrivals. She also described a rise in scams targeting immigrants, including impersonation of ICE agents who threaten arrests or demand payments in exchange for supposed protection from removal. Consumer advocates urge families to verify any contact directly through official channels and warn that no legitimate officer will request payment to avoid detention.

Community organizations have also alleged deceptive tactics by enforcement teams. Crisaly De Los Santos, director of CASA’s Baltimore and central Maryland branch, said ICE has used fake job postings to draw people to locations where they could be detained. Local leaders say those claims are difficult to prove in real time, but they track with broader reports that immigrants are avoiding job fairs and changing shift patterns to avoid exposure. CASA and other groups are expanding know-your-rights trainings and offering accompaniment to check-ins, but organizers say the sheer size of the recent arrest numbers makes it hard to keep pace.

Baltimore County’s MOU clarifies the flow of information inside jails and signals how local and federal systems will intersect in cases that begin with a traffic stop or an unrelated arrest. Under the agreement, when county corrections staff identify a person flagged by an immigration detainer or a federal warrant, they must communicate the detention and release timing to federal counterparts. That step alone can translate into more pickups at jail doors and higher detention totals within the Baltimore Area of Responsibility. For families, it means a sudden, sharp pivot: an expected release becomes a transfer into federal custody, often to a detention center hours away. Attorneys say that window, when coordination happens between county facilities and federal agents, can determine whether a person finds counsel quickly or ends up signing paperwork while confused and isolated.

The supply contract for 42,000 shelf-stable meals in Baltimore and Salisbury underlines the planning behind the expansion. Over six months, the meals could support transport operations, temporary staging at field offices, or contingency planning for larger enforcement actions—uses that procurement analysts often read as signals of operational intent, even when the paperwork lists only standard supply codes. Federal contracts of this kind are being watched closely by advocates and municipal leaders who say they are among the few early indicators of how and where enforcement surges may unfold. In Baltimore County, where officials emphasized that the MOU simply formalizes notice obligations, the presence of new federal contracts is nonetheless shaping public discussion about how deep the expansion could run.

National policy is nudging the region in the same direction. Washington has set out plans to more than double immigration detention capacity by the end of 2025, including a $1.2 billion contract for a new 5,000-bed facility at Fort Bliss, Texas. The spending surge is anchored by the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” signed on July 4, 2025, which allocates $170.1 billion in new funding for immigration enforcement, making ICE the highest-funded federal law enforcement agency in U.S. history. In practical terms for Maryland, that infusion means richer budgets for field operations, more transportation and detention slots, and a nationwide push that can quickly translate into additional personnel and activity in the Baltimore Area of Responsibility. Officials and advocates alike say those upstream decisions are now visible on local streets.

In immigrant neighborhoods from Highlandtown to Dundalk, residents describe a daily calculus shaped by risk: whether to go to work, whether to answer a knock at the door, whether to ride with a neighbor to save money on gas. Parents swap information about rumored checkpoints and carry folders with copies of birth certificates and medical records in case a pickup happens when children are at school. Business owners in Baltimore County say the fallout is immediate: staff calling out, deliveries rescheduled, and shelves staying full because customers no longer linger to browse. The effect compounds with every report of a raid or arrest, creating what local groups call an ambient pressure that is hard to quantify but easy to feel when streets turn “desolate” after dusk.

Supporters of stepped-up enforcement argue the changes reflect a necessary response to federal priorities and are made safer by formal coordination through the Baltimore County MOU. They point to the notification requirements as a way to ensure that individuals wanted on federal grounds are not inadvertently released without federal awareness. County officials say the agreement does not compel new arrests or alter the standards for holding anyone in county custody, a point they’ve emphasized as residents debate what “no longer a sanctuary jurisdiction” will mean in practice. Turner’s message, that the MOU

“makes no changes to the Department of Corrections’ standard practices,”

was intended to calm fears that county officers would begin proactive immigration enforcement, which remains the role of federal agents.

But for families already jarred by the arrest numbers and the visible ICE presence, assurances can feel abstract. Lopez’s warning that the moment is

“profoundly chilling”

echoes in calls to hotlines and across church basements where people gather for workshops on their rights. Attorneys report fuller calendars and tougher timelines; community organizers say they are spending more hours on safety planning and fewer on long-term integration work. Even where the county’s policy focuses on jail notifications rather than street-level enforcement, the broader network—including federal contracts for meals and expanded detention capacity—signals a system primed for more intakes.

As organizations try to keep pace, they are also urging caution against exploitation. Simpson’s account of rising scams, including impersonation of ICE agents, has prompted repeated reminders that enforcement officers do not request money to avoid arrest and that anyone approached should verify identities through official channels like the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement website or by contacting trusted legal service providers. De Los Santos’s allegation that fake job postings have been used to lure workers underscores the vulnerability many feel as they weigh whether to show up for opportunities that, in different times, would have been pathways to better wages.

The next phase will hinge on whether the tempo of arrests holds, how the six-month meal contract is used, and how the county-federal jail pipeline functions under the new MOU. Data from the first seven months of 2025 shows a region already on track for a record year of ICE enforcement. The geography of the Baltimore Area of Responsibility, which covers Maryland and parts of Virginia and Delaware, gives the field office a wide operational reach that can shift quickly in response to national directives. If federal plans to more than double detention capacity continue apace, Baltimore County could see more transfers from local jails to federal facilities, and more families confronting the choice Barrantes described between earning a paycheck and avoiding exposure.

For now, the picture is clear enough that both supporters and critics of the expansion agree on at least one point: the ground is moving. Federal contracts, a county-level MOU, and arrest figures that have already surpassed last year’s total are converging to reshape the enforcement landscape in Baltimore and Baltimore County. Whether residents view those changes as overdue coordination or as an unsettling turn, the effects are tangible—in the sudden quiet outside neighborhood bakeries, in the folders parents carry to be ready for the worst, and in the crowded calendars of lawyers and organizers bracing for what looks like a longer season of intensified ICE presence.

This Article in a Nutshell

Federal procurement of 42,000 shelf-stable meals and an Oct. 31, 2025 MOU between Baltimore County and DHS/ICE, combined with 2,280 arrests in the first seven months of 2025, indicate a growing ICE enforcement footprint in the Baltimore Area. County jails must notify ICE about detainers and releases, raising concerns among advocates about family separations, economic harm to immigrant businesses, increased expedited removals, and barriers to legal counsel. National detention expansion and funding increases amplify the local impact.