(HAWAIʻI) — People in Hawaiʻi—citizens and noncitizens alike—have core rights when immigration enforcement intersects with everyday life, including the right to remain silent, to refuse certain searches, and to insist that state and local officials follow due process before honoring federal civil immigration requests.

Those rights are at the center of a new “Immigration Justice” legislative campaign launched Monday, Jan. 12, 2026, by the ACLU of Hawai‘i, alongside the Hawai‘i Coalition for Immigrant Rights and The Legal Clinic.

The coalition is urging lawmakers to adopt what it calls “state veils”—state and local policy barriers meant to reduce unnecessary data-sharing and access pathways into federal immigration enforcement, while strengthening privacy and due process.

This guide explains the legal foundation for these rights, who has them, and how to exercise them in practical terms as Hawaiʻi’s 2026 session begins.

1) ACLU Hawai‘i campaign launch and goals: what “state veils” mean in practice

The campaign’s core claim is straightforward: even when federal immigration enforcement remains in place, state and local choices still shape how exposed residents are to immigration consequences.

Hawaiʻi cannot “turn off” federal authority. But it can often decide whether and how state and county systems participate.

In plain terms, advocates use “state veils” to describe policies that may:

- limit local participation in federal civil immigration enforcement;

- tighten privacy around school and healthcare records;

- require clearer informed consent before questioning by immigration agents; and

- create more consistent victim protections for people seeking U or T visas.

The campaign’s pillars, as described by organizers, include:

Sensitive locations. Policies that discourage or restrict civil immigration enforcement activity near schools, hospitals, courts, and shelters. These measures typically aim to keep residents accessing essential services.

Limits on law enforcement collaboration. Restrictions on local cooperation with immigration enforcement, including avoiding 287(g) arrangements.

A 287(g) agreement is authorized under INA § 287(g) and allows certain local officers to perform limited federal immigration functions after training and supervision.

Language access and informed consent. Requirements that people in custody receive rights information in a language they understand before any immigration interview or handoff.

Victim protections. More consistent certification for U and T visas. U visas are for certain crime victims who help law enforcement (INA § 101(a)(15)(U)). T visas are for certain survivors of trafficking (INA § 101(a)(15)(T)).

The legal boundary matters. Federal immigration enforcement is a federal power. States cannot prevent ICE from enforcing federal law.

But states can often restrict state resources from being used for civil immigration purposes. They can also set privacy and procedure rules for state-run institutions.

2) Key figures and quotes: what “local accountability” can mean

ACLU of Hawai‘i Executive Director Salmah Y. Rizvi framed the campaign as a response to aggressive federal enforcement and as a call for local decision-makers to set community-protective rules.

In brief remarks, Rizvi emphasized “state veils,” and pointed to local power to insist on accountability when federal agents act within Hawaiʻi.

Translated into daily life, “accountability of local law enforcement” usually means written policies and measurable practices, such as:

- clear rules on whether officers may honor ICE detainers without a judge’s approval;

- public reporting on how often detainers are received and honored;

- training on language access and what officers can lawfully ask;

- limits on stopping, arresting, or prolonging custody for civil immigration purposes; and

- complaint procedures when residents believe their rights were violated.

These choices tend to matter most in three settings.

Schools. Families may be more willing to attend meetings, enroll children, and request special education services when schools limit unnecessary status questions and protect student records.

Healthcare. Patients may be more likely to seek care when facilities do not ask for immigration status unless required, and when staff know how to respond to enforcement requests.

Local policing. Community members may report crimes more readily if they believe a traffic stop or witness interview will not become an immigration screen.

Warning: Asking for an interpreter is not a sign of guilt. If you do not understand English well, insist on language access. Miscommunication can lead to accidental waivers.

3) Federal backdrop: USCIS and DHS statements in 2025–2026, and why they matter

Even though USCIS is a benefits agency, public DHS and USCIS statements can still shift real-world conditions. They may signal changes in enforcement emphasis and coordination language.

Statements can also affect screening and fraud review posture in adjudications, travel-related vetting and post-entry compliance checks, and how aggressively agencies pursue “sanctuary” disputes with states.

The recent federal messaging described in USCIS and DHS materials in late 2025 and early 2026 has emphasized enforcement integrity, national security screening, and criticism of sanctuary-style policies.

One USCIS memo referenced expanded travel restrictions and heightened attention to “high-risk” countries, including the use of adjudicative holds and re-reviews for certain cases.

For Hawaiʻi residents, the practical takeaway is not theoretical. Federal posture can affect whether applicants experience longer processing times or additional interviews.

It can also affect whether travel triggers extra screening or delays at ports of entry, whether people fear contact with schools, clinics, and police, and whether local governments face pressure to increase cooperation.

That is the policy space in which “state veils” operate. When federal agencies tighten screening or step up enforcement rhetoric, states often respond by clarifying limits on local participation and strengthening privacy and due process norms.

4) The 2026 Hawai‘i bills: what they would do and how rights are lost in practice

Advocates are backing several bills that align with the campaign’s pillars. Because bill language can change through amendments, readers should track the latest versions through the Hawaiʻi Legislature.

SB775: detainers vs. warrants, explained

SB775 would prohibit state and local law enforcement from complying with civil immigration detainers without a judicial warrant.

A civil immigration detainer is typically a request from ICE asking a jail to hold someone for extra time, or to notify ICE before release. A detainer is not the same as a criminal arrest warrant signed by a judge.

A judicial warrant is issued by a judge or magistrate and is generally associated with criminal process. Requiring a judicial warrant can change the default rule and may reduce holds based only on civil immigration requests.

Why this matters: the Fourth Amendment prohibits unreasonable seizures. Courts have repeatedly litigated detainer-related holds. Outcomes can vary by jurisdiction and facts.

People held beyond their release time may later argue the hold was unlawful.

How to exercise the right in practice if you are in custody:

- Ask, calmly: “Am I free to go?”

- If told you are being held for ICE, ask: “Do you have a judicial warrant?”

- Ask for a lawyer immediately if you face questioning.

SB856 / SB818: education and healthcare privacy

SB856 and SB818 would create standards for covered educational entities and health facilities to protect privacy about immigration status.

Operationally, policies like these often address when staff may ask about immigration status, if at all; how records requests are handled; what happens if an agent requests access to a student or patient; and who must be contacted internally before any cooperation.

These proposals intersect with existing privacy regimes. For schools, federal student record protections under FERPA often limit disclosure without consent, with specific exceptions.

For healthcare, HIPAA typically restricts disclosure of protected health information without authorization, again with exceptions.

SB853: Immigration Services Trust Fund

SB853 would establish an Immigration Services Trust Fund. Trust funds of this type may support legal services, “know your rights” education, and navigation to social services.

Implementation details matter, including eligibility rules, grant administration, and oversight.

How a bill becomes law in Hawaiʻi (and why timing matters)

Most bills follow a path: introduction, committee hearings, committee votes, floor votes, conference committee if needed, and then the governor’s decision.

Deadline watch: Committee hearings can move quickly. If you want to submit testimony, you typically need to do so before the hearing time listed on the Legislature’s notice.

5) Impact and statistics in Hawai‘i: why the numbers matter

Hawaiʻi’s debate is not abstract. The immigrant community has a significant footprint. The data cited by advocates reflects about 254,000 immigrants living in Hawaiʻi.

Advocates also cite about 50,500 undocumented individuals and about 7% of public school students having at least one undocumented parent.

Mixed-status families are common. That means a single enforcement encounter can affect U.S. citizen children, lawful permanent residents, visa holders, and undocumented relatives at once.

Enforcement surges also have ripple effects beyond the targeted person. Schools can see reduced attendance. Employers can face abrupt staffing disruptions.

Victims and witnesses may avoid reporting crimes if they fear immigration consequences.

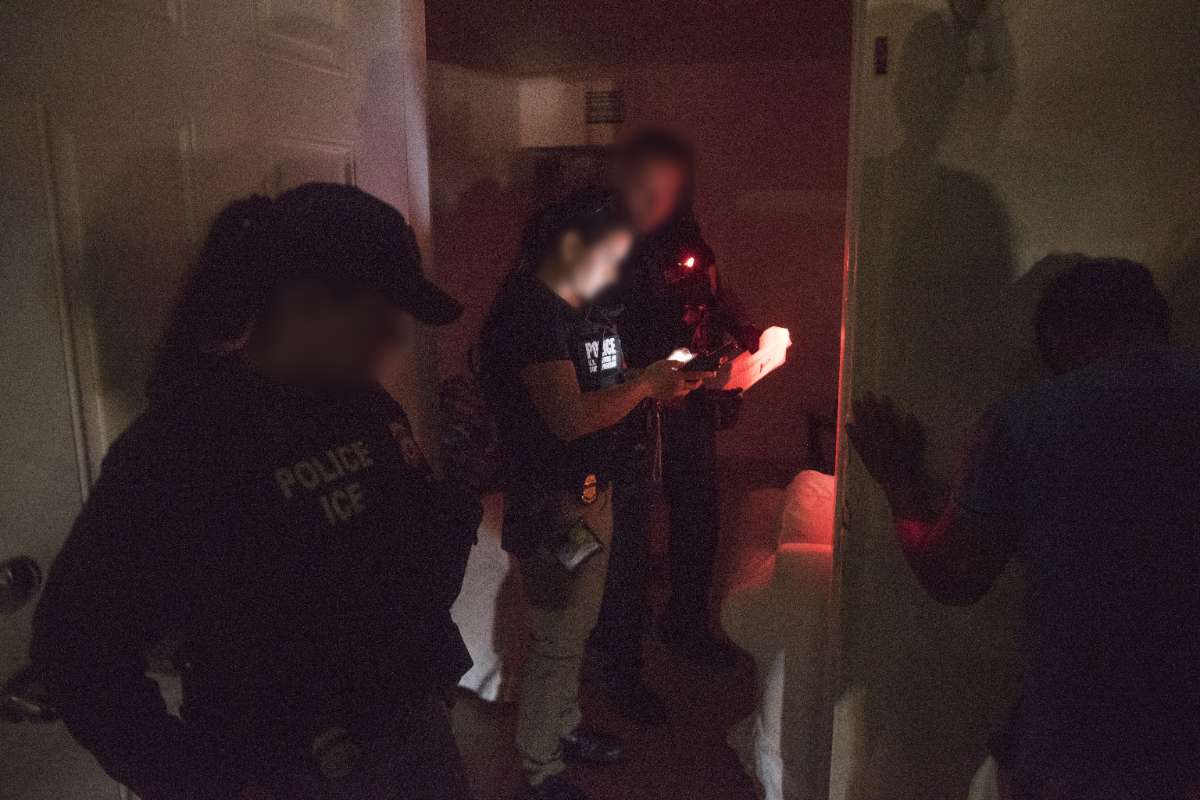

A 2025 incident cited by advocates involved the detention of over 10 Filipino teachers on Maui in their homes. Regardless of the final outcomes in those cases, the event illustrates a recurring pattern: high-visibility enforcement can chill community participation in schools, unions, clinics, and police reporting.

In that context, the policy debate over privacy, language access, and U/T visa certification becomes more than symbolic. These are the pressure points that often determine whether residents seek help, cooperate with investigations, or access legal counsel early.

Warning: Travel can carry extra risk for noncitizens. CBP controls entry at ports. Even people with valid visas or green cards may face questioning. Consider legal advice before international travel if you have arrests, prior removal, or pending cases.

Exercising your rights: who has them, what to say, and common waiver traps

Who has these rights?

Many key protections apply to everyone in the United States, including undocumented people.

Right to remain silent: Rooted in the Fifth Amendment. You can refuse to answer questions about where you were born or how you entered.

Protection against unreasonable searches and seizures: Fourth Amendment. Police typically need consent or legal authority to search you or your home.

Due process: Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. Noncitizens in removal proceedings have statutory rights too. See, for example, the right to counsel at no government expense under INA § 240(b)(4)(A).

What to say (and what not to do)

- “I am going to remain silent.”

- “I do not consent to a search.”

- “I want to speak with a lawyer.”

Do not lie or present false documents. Misrepresentation can trigger serious immigration consequences. Depending on the context, it may implicate INA § 212(a)(6)(C) or criminal exposure.

Common ways rights are waived

- Consenting to a search because you feel pressured.

- Signing papers you do not understand. Some people sign voluntary departure or stipulated orders without counsel.

- Talking “just to explain.” Small details can be used later.

Warning: If ICE comes to your door, ask for a warrant signed by a judge and ask to see it through a window. An administrative ICE warrant is not the same as a judicial warrant.

If your rights are violated: practical steps

- Write down details immediately. Names, badge numbers, agency, time, location, witnesses, and what was said.

- Preserve documents. Keep copies of detainers, notices, bond paperwork, and any receipts.

- Request records when appropriate. Lawyers may seek jail logs, body camera footage, or detainer communications.

- Get qualified legal help early. Immigration consequences can move faster than court timelines.

Official government sources and where to find more

For primary documents and updates, start with:

- USCIS Newsroom (policy announcements and operational updates): https://www.uscis.gov/newsroom

When you find an important page, save a PDF or screenshot for your records. Online content can change.

For legal help, many people start with a private attorney through AILA’s directory.

- Resources

- AILA lawyer directory

⚖️ Legal Disclaimer: This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.

The ACLU of Hawai‘i’s 2026 Immigration Justice campaign introduces ‘state veils’ to protect the rights of the state’s 254,000 immigrants. By pushing for bills like SB775 and SB856, the coalition seeks to restrict local police cooperation with ICE and protect privacy in schools and healthcare. The movement highlights the legal distinction between federal authority and state-managed resources, emphasizing due process and informed consent.