- Virginia legislators are proposing judicial warrant requirements for civil immigration arrests occurring within state courthouses.

- Individuals in courthouses retain Fourth and Fifth Amendment rights, including the right to remain silent during encounters.

- The DHS opposes these limits, arguing they restrict federal enforcement discretion and potentially compromise officer safety.

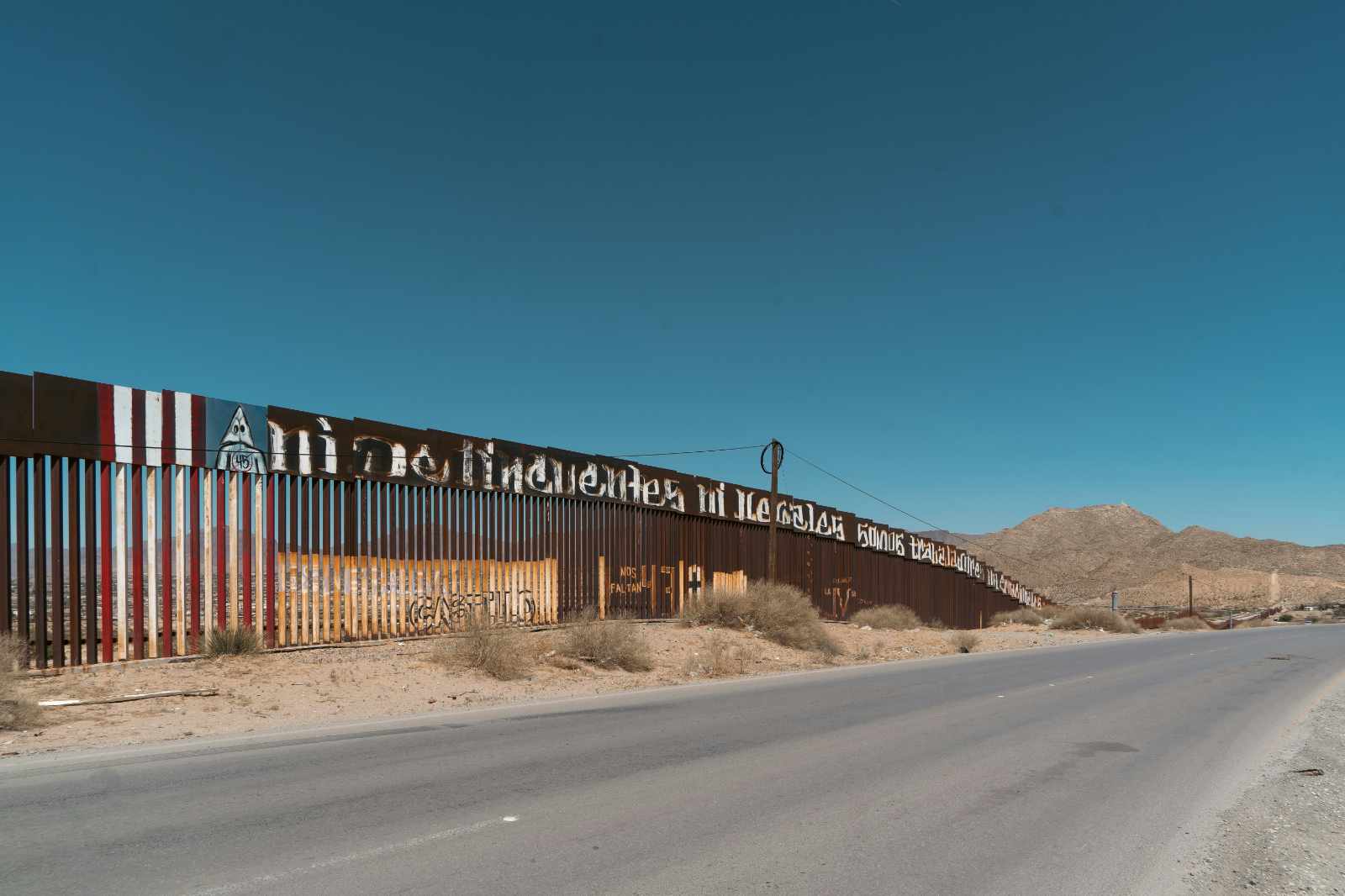

(VIRGINIA, UNITED STATES) — People who enter Virginia courthouses—whether as defendants, witnesses, victims, family members, or attorneys—generally have the right to be free from unreasonable seizures and to decline consent-based questioning, even when federal immigration officers are present.

This rights guide explains the legal baseline for immigration arrests in courthouses, what two Virginia Democrats–backed bills would change for courthouse procedures, and how individuals can exercise core constitutional and statutory rights without accidentally waiving them.

It also summarizes DHS/ICE’s stated objections and the practical stakes for court access and due process.

The specific right: freedom from unreasonable seizure—and the right to remain silent in civil immigration encounters

Legal basis (high level)

Several overlapping legal rules shape courthouse encounters.

- Fourth Amendment (U.S. Constitution): Protects against unreasonable searches and seizures. In practice, officers typically need probable cause to arrest, and may need a judicial warrant in some settings.

- Fifth Amendment: Protects against compelled self-incrimination. In immigration encounters, you generally may refuse to answer questions about where you were born or your status.

- INA § 287 (8 U.S.C. § 1357): Grants federal immigration officers authority to interrogate and arrest in certain circumstances.

- 8 C.F.R. § 287.8: Sets standards for immigration officer conduct, including stops, questioning, and arrests.

- Right to counsel in removal proceedings: INA § 292 (8 U.S.C. § 1362) provides a right to counsel at no government expense in immigration court, and EOIR advisals appear in 8 C.F.R. § 1240.10.

Courthouse enforcement disputes often turn on a key distinction: “administrative” immigration warrants versus judicial warrants signed by a judge.

Warning: Courthouse encounters can move fast. A person may waive protections by consenting to questioning, signing papers, or following an officer outside without clarifying whether they are free to leave.

Who has these rights?

These baseline rights apply broadly to different categories of people who may be present in courthouses.

- U.S. citizens: Full constitutional protections; may refuse to answer immigration questions. Citizens can still be detained briefly if officers claim a lawful basis, but citizenship is a complete defense to removal.

- Lawful permanent residents (LPRs): Fourth and Fifth Amendment protections apply; LPRs may still be placed in removal proceedings in some cases.

- Visa holders and other lawful statuses: Same basic constitutional protections; immigration consequences can follow arrests or statements.

- Undocumented individuals: Still have Fourth and Fifth Amendment protections. Many disputes focus on how those rights play out during civil immigration enforcement.

How to exercise the right in practice (plain language)

If approached by immigration officers in or near a courthouse, there are concrete steps that help preserve legal rights.

- Ask if you are free to leave. If the answer is “yes,” you may leave calmly.

- If you are not free to leave, say you want a lawyer. You may request to speak with an attorney before answering substantive questions.

- Use silence carefully. You can state: “I am exercising my right to remain silent.” Then stop talking.

- Do not consent to searches. You can say: “I do not consent to a search.” Do not physically resist.

- Ask to see the warrant. If an officer claims a warrant, ask to read it. Note whether it is signed by a judge.

These steps do not guarantee an outcome. They help preserve issues for a lawyer to evaluate later.

1) Official DHS/ICE statements and timeline: why the federal government opposes courthouse limits

DHS and ICE messaging in late 2025 and early 2026 has been consistent: the agency opposes state-level measures that it views as restricting federal enforcement discretion.

In public statements tied to increased enforcement activity, DHS framed courthouse operations as a legitimate setting for arrests because people with pending local cases are already present, identified, and screened for weapons.

DHS has also argued that limiting enforcement in courthouse areas may push arrests into less controlled environments, which it claims can increase risk to the public and to officers.

As Virginia Democrats advanced bills aimed at limiting immigration arrests in or around courthouses, DHS emphasized three themes:

- Public safety framing: DHS says its focus is removing individuals it characterizes as serious threats.

- Officer safety: DHS has pointed to rising assaults on officers and argues restrictions can heighten operational risk.

- Federal authority and discretion: DHS asserts immigration enforcement is federally assigned and should not be constrained by state procedure.

Readers should treat DHS statements as policy messaging, not as a complete statement of legal limits. The binding limits usually come from statutes, regulations, and court orders.

2) Key facts and policy details: what Virginia bills HB650 and SB351 would do in courthouse settings

Two proposals—HB650 and SB351—are designed to change how courthouse arrests may occur in Virginia by adding procedural requirements tied to warrants, identification, and documentation.

A. “Judicial warrant required” for civil immigration arrests in courthouses

At a high level, the bills would prohibit certain civil immigration arrests in courthouses unless agents present a judicial warrant signed by a judge.

This matters because many ICE civil arrests rely on administrative warrants (often on DHS forms) authorized internally by immigration officials. Administrative warrants can be lawful tools for civil immigration enforcement. But they are not the same as a judge-signed warrant.

In practice, a judicial-warrant requirement would likely mean:

- Court staff may ask for proof that a judge signed the warrant.

- Arrest activity could be delayed or blocked absent that judicial document.

- Disputes may shift to what counts as “in and around” a courthouse and what counts as “civil” versus “criminal” enforcement activity.

B. Identification and credential display requirements

The bills would also require federal agents to identify themselves and present credentials to courthouse personnel.

Operationally, these provisions aim to reduce confusion when officers are in plain clothes and to create clearer lines of accountability for court administrators tasked with maintaining safety and access.

C. Warrant review and written confirmation

A key workflow concept in the bills is a review-and-confirmation step: a designated judicial officer or attorney would review the warrant and provide written confirmation before an arrest proceeds.

Why written confirmation matters:

- It creates a record that the courthouse verified the warrant type.

- It reduces “he said, she said” disputes after an incident.

- It may shape later litigation about compliance and remedies.

D. Enforcement mechanisms: contempt and civil relief (conceptual overview)

The bills contemplate consequences if officers do not follow the courthouse procedures, including:

- Contempt of court: A court’s power to enforce compliance with its lawful orders and protect court operations.

- Civil action for relief: Affected individuals may seek remedies in court.

These mechanisms are procedural and fact-dependent. They also raise federalism questions. States can regulate courthouse administration, but they generally cannot nullify federal enforcement authority.

Warning: Even if a state law adds courthouse procedures, it may not stop federal enforcement everywhere. Enforcement disputes can turn on location, timing, and whether an arrest is framed as civil or criminal.

3) Context and significance: ICE activity, reported incidents, and a key federal injunction

Reported “surge” in 2025 courthouse activity—what that often means

When officials and advocates describe a “surge” in courthouse enforcement, they usually mean more frequent officer presence on docket days and more visible enforcement in hallways, entrances, or parking areas.

They often also mean more strategic timing, such as after a dismissal or continuance.

Illustrative Virginia incidents (kept factual and non-sensational)

Reports from 2025 described arrests involving masked or plainclothes agents at or near courthouses in:

- Charlottesville (Albemarle County Courthouse)

- Chesterfield

- Sterling (Loudoun County)

These incidents became flashpoints because they allegedly occurred after minor matters were resolved, and because people reported confusion about officer identity and authority.

The Dec. 3, 2025 injunction by U.S. District Judge Beryl Howell (D.C.)

On Dec. 3, 2025, U.S. District Judge Beryl Howell issued a preliminary injunction described as requiring documentation of probable cause and likelihood of escape before certain warrantless civil arrests.

At a high level, preliminary injunctions typically bind the parties before the court (and sometimes those acting in concert), operate while litigation continues, and can be narrowed, expanded, stayed, or reversed on appeal.

This kind of order may change on short notice. It also does not automatically apply nationwide.

How state bills and federal court orders can interact

If Virginia enacts courthouse procedures, they may function alongside federal litigation in a few ways.

- State rules may shape how courthouse staff respond to officer requests.

- Federal injunctions may shape what federal officers are allowed to do in covered circumstances.

- Neither system fully replaces the other. Conflicts can trigger additional litigation.

4) Impact on individuals: victims, witnesses, and due process inside courthouses

Courthouses are where people seek protective orders, defend traffic tickets, finalize custody arrangements, and testify in criminal cases.

When people fear immigration arrests at courthouses, participation in the justice system may drop.

Victims and witnesses: why presence (or perceived presence) matters

Prosecutors and lawmakers supporting the bills argue that visible immigration enforcement can deter important participants from coming to court.

- Domestic violence survivors seeking protective orders

- Witnesses needed to prove assaults, thefts, or fraud

- Family members attending civil proceedings

DHS responds that it targets individuals it frames as public safety threats, and that courthouse operations are controlled settings.

Critics reply that the practical net can capture people with minor or no convictions and can chill reporting.

Due process concerns to recognize

Advocates have raised concerns about arrests that appear timed to courthouse exits or dismissals, and about confusion over whether an officer has a judge-signed warrant.

From a rights perspective, the core due process issues often include access to counsel, clarity of authority, and documentation.

- Access to counsel: People may be separated from their attorney at the moment a local case ends.

- Clarity of authority: Plainclothes operations can leave bystanders unsure who is acting under what authority.

- Documentation: A written record of warrant type and review can matter later.

The proposed bills would not create a right to avoid arrest. They would aim to change the procedure—identity display, warrant confirmation, and documentation—before a civil courthouse arrest can proceed.

Impact snapshot (as commonly framed in policy discussions):

- High impact: Victim/witness participation and willingness to appear in court.

- Medium impact: Day-to-day courthouse administration and attorney-client coordination on docket days.

Warning: Signing documents in custody can waive rights. People sometimes sign papers they do not understand to “get out faster.” Those decisions can have lasting immigration consequences.

What to do if you believe your rights were violated

If an incident occurs, consider these steps as soon as it is safe.

- Document details: Names, badge numbers, agency, location, time, and witnesses.

- Ask for paperwork: Warrants, notices, and charging documents.

- Tell your immigration lawyer immediately. A lawyer may evaluate whether suppression or termination arguments exist.

In immigration court, suppression is limited, but it can be available in some circumstances. The Supreme Court held that the exclusionary rule generally does not apply in removal proceedings, with potential exceptions. See INS v. Lopez-Mendoza, 468 U.S. 1032 (1984).

The BIA has addressed suppression frameworks and burdens in decisions such as Matter of Barcenas, 19 I&N Dec. 609 (BIA 1988), and regulatory-violation analysis in Matter of Garcia-Flores, 17 I&N Dec. 325 (BIA 1980). Outcomes vary by facts and circuit law.

For court-process information, EOIR’s site is a starting point: https://www.justice.gov/eoir.

5) Official government sources and how to verify what changes next

How to track HB650 and SB351 reliably

The most reliable method is the Virginia Legislative Information System (LIS). On a bill page, look for different elements that show the bill’s progress and text.

- Versions: Introduced, substitute, engrossed, and enacted text can differ.

- Amendments: Committee changes may be significant.

- Committee actions and calendars: These show whether a bill is moving.

- Effective date language: Some laws apply later or have conditions.

Deadline watch: Committee votes and crossover deadlines in a legislative session can change quickly. Check the LIS “history” and committee calendar before relying on older summaries.

How to read DHS statements

DHS statements often reflect policy priorities and messaging. They can be important context, but they are not the same as statutes, regulations, or binding court orders.

What to monitor next

As the Virginia proposals move, watch for amendments narrowing or expanding “courthouse” definitions and any “in and around” boundary language changes.

Also monitor litigation over preemption or enforceability if enacted, and updated guidance from Virginia court administrators on implementation.

Resources for legal help

– AILA Lawyer Referral: https://www.aila.org/find-a-lawyer

– Immigration Advocates Network (legal directory)

If you or a family member is in removal proceedings, you can also consult the EOIR portal and guidance at https://www.justice.gov/eoir.

This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.