- Students demand clear limits on campus ties to federal immigration enforcement at USF.

- The 287(g) program deputizes local police to perform specific civil immigration functions under federal supervision.

- International students face heightened visa scrutiny and should verify documentation before any international travel.

(TAMPA, FLORIDA, UNITED STATES) — A growing number of University of South Florida (USF) students say they want clear, written limits on campus ties to immigration enforcement, and a transparent process for how university police interact with federal agencies when routine encounters might turn into immigration cases.

The January 2026 protests—organized locally by Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in the Tampa Bay area—are not only about politics. They are also about process: how a university enters a federal partnership, what authority campus police gain under that partnership, what information is shared, and what practical steps students (including international students and mixed-status families) can take to reduce avoidable immigration risk while still exercising their rights.

Below is a process explainer focused on how these partnerships typically work, the decision points that change outcomes, and the documents that matter.

1) Start with what the process accomplishes—and who needs it

A campus immigration-enforcement “process” is the chain of actions that begins when a school or its police department coordinates with DHS components like ICE or CBP, and ends with one of several results: no referral, an ICE interview, an immigration hold request, removal proceedings in immigration court, or sometimes a visa-related consequence for noncitizens.

This process matters most for:

- International students in F-1 or J-1 status and their dependents.

- Students in mixed-status families, including undocumented students.

- Anyone who could have law-enforcement contact (traffic stops, protests, dorm calls).

- Campus employees and student groups worried about surveillance or “chilling effects.”

Two baseline legal concepts shape everything:

- Visa vs. status: A visa stamp is for entry. “Status” is the classification that governs your stay after admission. A visa can be revoked while a person may still remain in status in the U.S., depending on facts.

- Civil immigration vs. criminal law: Most immigration violations are civil. But arrests, charges, or convictions can trigger separate consequences.

2) Step-by-step: how a 287(g) task force partnership typically becomes real on campus

The controversy at USF centers on the 287(g) program, which is authorized by INA § 287(g) and implemented through agreements between ICE and local agencies. USF police reportedly entered the task force model in 2025.

Below is the typical process flow for task force partnerships and campus application. This section explains the documents and decision points that commonly determine outcomes.

Step 1 — The agency signs a 287(g) agreement and MOA

What happens: A local agency signs a memorandum of agreement (MOA) with ICE. The MOA defines scope, training, supervision, reporting, and permitted functions.

Key document(s):

- 287(g) MOA (often posted by ICE or obtainable through public records in many jurisdictions).

- Related agency policies or general orders.

Decision point: The model matters. Task force agreements are different from jail screening models. The authority and setting differ.

Warning: A 287(g) agreement does not automatically mean every campus police contact becomes immigration enforcement. Scope depends on the MOA and agency policy.

Step 2 — Selected officers are trained and supervised by ICE

What happens: Designated officers attend ICE training and operate under ICE supervision for specified functions. In task force models, this may occur during certain operations or referrals.

Key document(s):

- Training records and designation letters (often not public in full).

- ICE program guidance.

Typical delays: Training and staffing can slow implementation. Universities may also revise procedures after public pressure or litigation.

Step 3 — A routine encounter creates an “immigration relevance” trigger

What happens: A contact that begins as normal policing can become immigration-relevant. Common triggers include identity questions, warrants, database checks, or arrest booking.

Key document(s):

- Incident report.

- Arrest affidavit, if any.

- Booking paperwork, if detention occurs.

Decision point: Outcomes vary sharply based on whether the encounter ends in:

- No arrest and no referral.

- Arrest with release.

- Arrest with extended custody, which can create time for ICE coordination.

Step 4 — ICE is contacted (or information is shared) under policy

What happens: Information may be shared through established channels. Whether that is allowed, and what is shared, can vary.

Key document(s):

- Agency policy on information sharing.

- Any ICE detainer paperwork, if used.

Common mistake: Assuming “campus police” equals “school administration.” They are linked, but different. Requests should distinguish USF administration from USF police policies.

Step 5 — Detainers, transfer, or immigration court proceedings may follow

What happens: ICE may seek continued custody or begin removal proceedings. Many people enter court only after ICE files a Notice to Appear (NTA).

Key document(s):

- Form I-247 series detainer paperwork (if issued).

- Notice to Appear (charging document for immigration court).

- Bond paperwork, if applicable.

Legal backdrop: Immigration court is EOIR. The path is Immigration Court → BIA → federal circuit court.

3) The “Handshake” controversy: how recruiting posts become a flashpoint

The January 2026 protest surge followed a CBP recruitment post appearing on Handshake, a common university career platform. Universities frequently describe these as third-party postings, not institutional sponsorship. USF’s public messaging reportedly emphasized that “external” listings are not endorsements.

Why it matters in practice:

- For students, a recruitment post can feel like institutional alignment with enforcement.

- For administrators, the key process question is who approves posts, what is labeled “external,” and what oversight exists.

Practical document requests students often make:

- Career services policies for third-party employers.

- Written criteria for “external event” labeling.

- Complaint or review channels for postings.

4) Florida’s enforcement context: why statewide choices affect campus outcomes

Florida’s heavy participation in 287(g) increases the chance that routine encounters across jurisdictions may lead to immigration referrals. That context can bleed into campus expectations, even when the campus itself is a separate agency.

Two terms students hear often:

- 287(g): deputizing certain functions under federal supervision.

- Detainers: ICE requests that a local agency hold someone briefly or notify ICE. Cooperation practices vary and are legally contested in some places.

State-level directives and political signals can influence agency culture, training priorities, and how aggressively referrals are made. That can amplify student anxiety, especially for those who do not know whether campus police follow the same escalation steps as city or county agencies.

Deadline / Timing Note: Immigration consequences often move faster than campus discipline. If an arrest occurs, consult counsel immediately. Early decisions can affect bond and court strategy.

5) International students: visa revocations, screening, and practical risk decisions

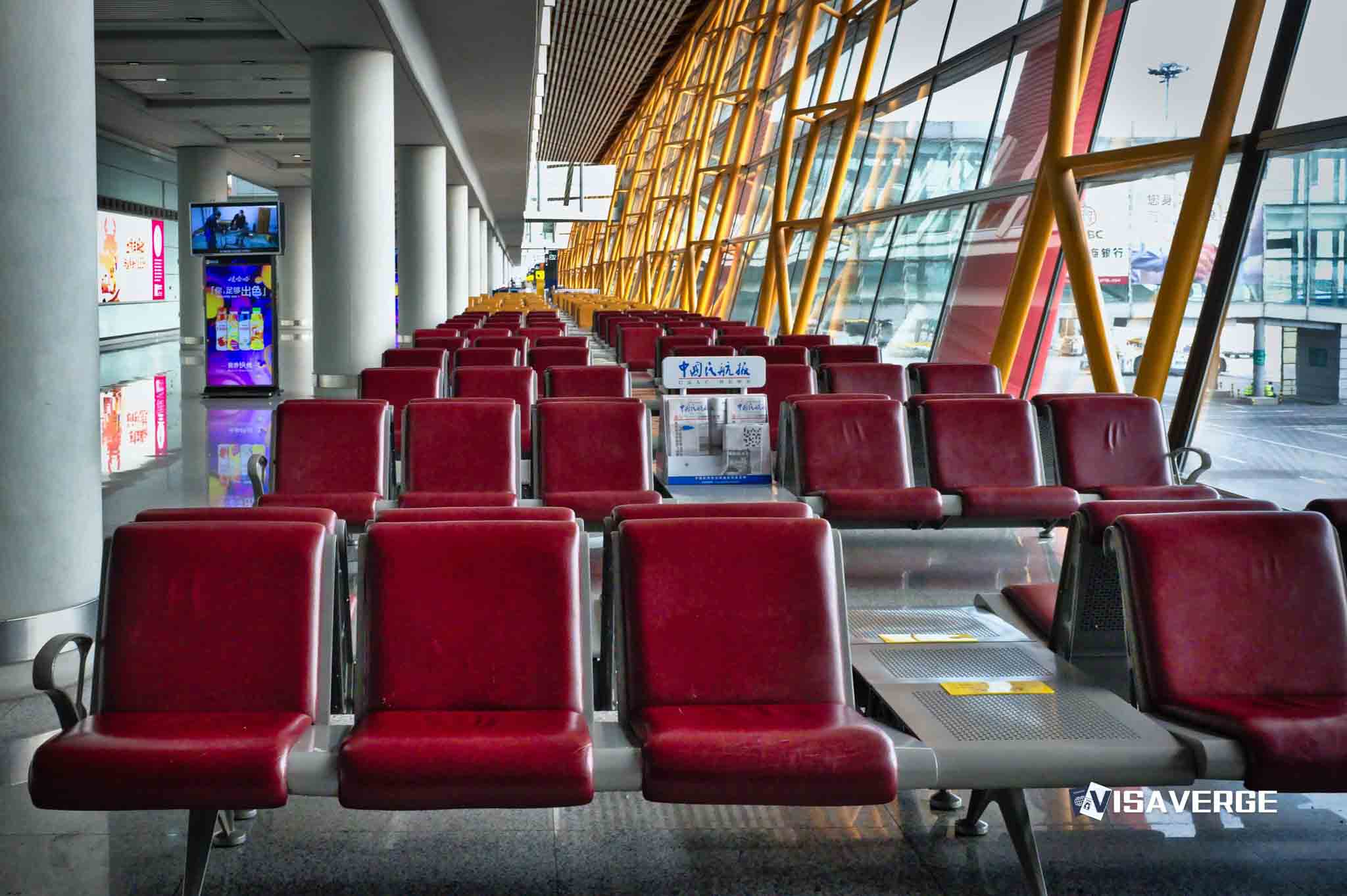

Organizers point to heightened visa scrutiny nationwide. Public reporting has described thousands of student visa revocations since early 2025, and USF enrolls several thousand international students.

Even when revocations are not tied to convictions, the climate can change how students assess travel and protest participation.

Key distinctions for F-1/J-1 students:

- Visa stamp: Used to request entry at a port of entry. A revoked visa can create travel barriers.

- Status in the U.S.: Governed by admission and compliance. For F-1 students, this typically means a valid I-20, full-time enrollment, and authorized employment. Regulations are detailed at 8 C.F.R. § 214.2(f).

- Unlawful presence: A technical concept with high stakes. It is not identical to being “out of status.”

Process steps for students who want to reduce avoidable risk:

- Confirm your documents: passport validity, I-20/DS-2019, I-94, and SEVIS accuracy with your DSO.

- Treat travel as a decision point: a revoked visa may not matter until you depart and need reentry.

- If arrested or cited: ask counsel how criminal charges may affect immigration. Many immigration consequences flow from criminal dispositions.

- If contacted by ICE: do not guess your way through questions. Ask for counsel.

Warning: Social media and protest activity can intersect with immigration screening. The legal relevance depends on facts, speech, and allegations. Do not assume “nothing will happen.”

6) Incidents that fuel mobilization: why narratives affect perceived risk

SDS and other critics often cite high-profile enforcement incidents and large operations to argue that partnerships increase danger. Those narratives can be intensified by multi-agency actions with rapid arrest counts, even when individual circumstances differ.

A careful way to evaluate claims is to separate:

- Verified government statements about broader enforcement priorities.

- Confirmed local policies (MOAs, written procedures).

- Allegations made in litigation or protests that have not been adjudicated.

This distinction matters because students make decisions based on perceived risk. Universities also respond differently when asked for documents versus asked to adjudicate contested facts.

7) Practical impacts, rights, and next steps (without guessing outcomes)

When immigration enforcement feels “close,” students may hesitate to report crimes or seek services. That is one of the central trust concerns raised about campus police participation in enforcement programs.

USF’s SDS chapter history also highlights how immigration anxiety can intersect with campus governance and civil-rights claims. If a student organization alleges retaliation or viewpoint discrimination, those claims typically proceed through university processes and, sometimes, litigation.

The facts and legal standards are case-specific, and outcomes vary.

Actionable next steps for students and families:

- Find the controlling documents: the USF police policy manual sections on immigration cooperation, and the ICE 287(g) MOA terms.

- Use written questions: ask the university to explain, in writing, when campus police may contact ICE and what records are created.

- Document responsibly: keep copies of notices, emails, and incident reports. Avoid interfering with law enforcement.

- Know the court ladder: Immigration Court (EOIR) → BIA → federal circuit courts.

- Get case-specific counsel early: especially if there is any arrest, pending charge, prior removal order, or travel plan.

For legal framing, students often hear about due process and detention authority. The Supreme Court has addressed prolonged detention limits in Zadvydas v. Davis, 533 U.S. 678 (2001), though applicability depends on posture.

In removal defense strategy, the BIA’s framework in Matter of M-A-M-, 25 I&N Dec. 474 (BIA 2011) is frequently cited for competency issues when they arise, and Matter of Pickering, 23 I&N Dec. 621 (BIA 2003) is often discussed when vacated convictions are involved. These are examples of how technical the law becomes once a case enters court.

⚖️ Legal Disclaimer: This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.

Official government information (for process basics)

– USCIS newsroom: https://www.uscis.gov/newsroom

– EOIR Immigration Court information: https://www.justice.gov/eoir

Resources:

University of South Florida students are advocating for transparent limits on campus police cooperation with federal immigration agencies. Centered on the 287(g) program, the article outlines the process by which routine campus policing can trigger immigration consequences. It provides essential guidance for international and mixed-status students regarding documentation, travel risks, and the legal framework of removal defense while emphasizing the importance of obtaining case-specific legal counsel.