(UNITED STATES) — Stephen Miller’s description of the U.S. asylum system as a “multibillion dollar fraudulent industry” is not just political messaging; paired with DHS/USCIS Operation PARRIS, it signals tighter screening, more post-admission checks, and higher stakes for refugees and asylum seekers already in the pipeline.

Section 1: What’s being claimed about the asylum system—and why it matters

Stephen Miller, speaking on February 2, 2026, framed the asylum system as a fraud-driven engine built to delay removals. He argued that people facing deportation “automatically file fake asylum applications” with “free and functionally unlimited legal services,” calling it “gross, unethical, and deeply immoral.”

He also claimed there are “no ‘asylum seekers’ on the Southern Border,” saying asylum fits only narrow categories of state persecution that do not match today’s arrivals. That rhetoric matters because it sets the tone for how agencies apply discretion and where they spend resources.

A speech does not change the law by itself. Still, public framing often shows up later as stricter vetting, broader fraud referrals, and more aggressive review of already-approved cases.

Separating messaging from binding rules helps readers track what actually affects a case. Binding changes usually come from written agency directives, published regulations, USCIS Policy Manual updates, or court-ordered limits on enforcement actions. Those are the items that shift timelines and outcomes. Fast.

Section 2: What DHS and USCIS have officially said (and what that typically signals)

DHS communications on January 9, 2026 announced a new enforcement initiative against alleged immigration fraud. A DHS spokesperson said the operation shows the administration “will not stand idly by” while the immigration system is “weaponized” to “defraud the American people,” adding that “American citizens and the rule of law come first, always.”

This is the language of deterrence and enforcement, not routine case management. DHS Secretary Kristi Noem reinforced that posture on January 13, 2026, using “restore integrity” and “rampant fraud” as themes when terminating Somalia’s Temporary Protected Status (TPS).

Integrity talk often has a practical meaning inside adjudications: officers may ask for more documents, schedule more interviews, and coordinate more often with enforcement components.

- More Requests for Evidence (RFEs) and Notices of Intent to Deny (NOIDs)

- Extra interviews, including second interviews

- Expanded background and identity checks through interagency systems

- More fraud referrals and case re-openings where rules allow

⚠️ Note: Changes to refugee reverification and asylum vetting can affect pending green-card applications and rights to due process; readers should verify official guidance before any actions.

Section 3: Operation PARRIS: what it is, who it targets, and how broad it could become

Operation PARRIS is short for Post-Admission Refugee Reverification and Integrity Strengthening. DHS/USCIS Operation PARRIS launched on January 9, 2026. “Post-admission reverification” means the government re-checks parts of a refugee’s case after the person has already been admitted to the United States.

Minnesota is the initial focal point. The first target group is 5,600 refugees in Minnesota who have been admitted but are not yet lawful permanent residents (not yet green-carded). That matters because many refugees apply for a green card later through adjustment of status, and those pending filings can become the natural touchpoint for new questioning.

DHS has also described a much broader review intent: 233,000 refugee approvals from January 2021 to February 2025. A targeted review can expand if agencies decide similar fact patterns exist elsewhere, or if data checks trigger flags in other locations.

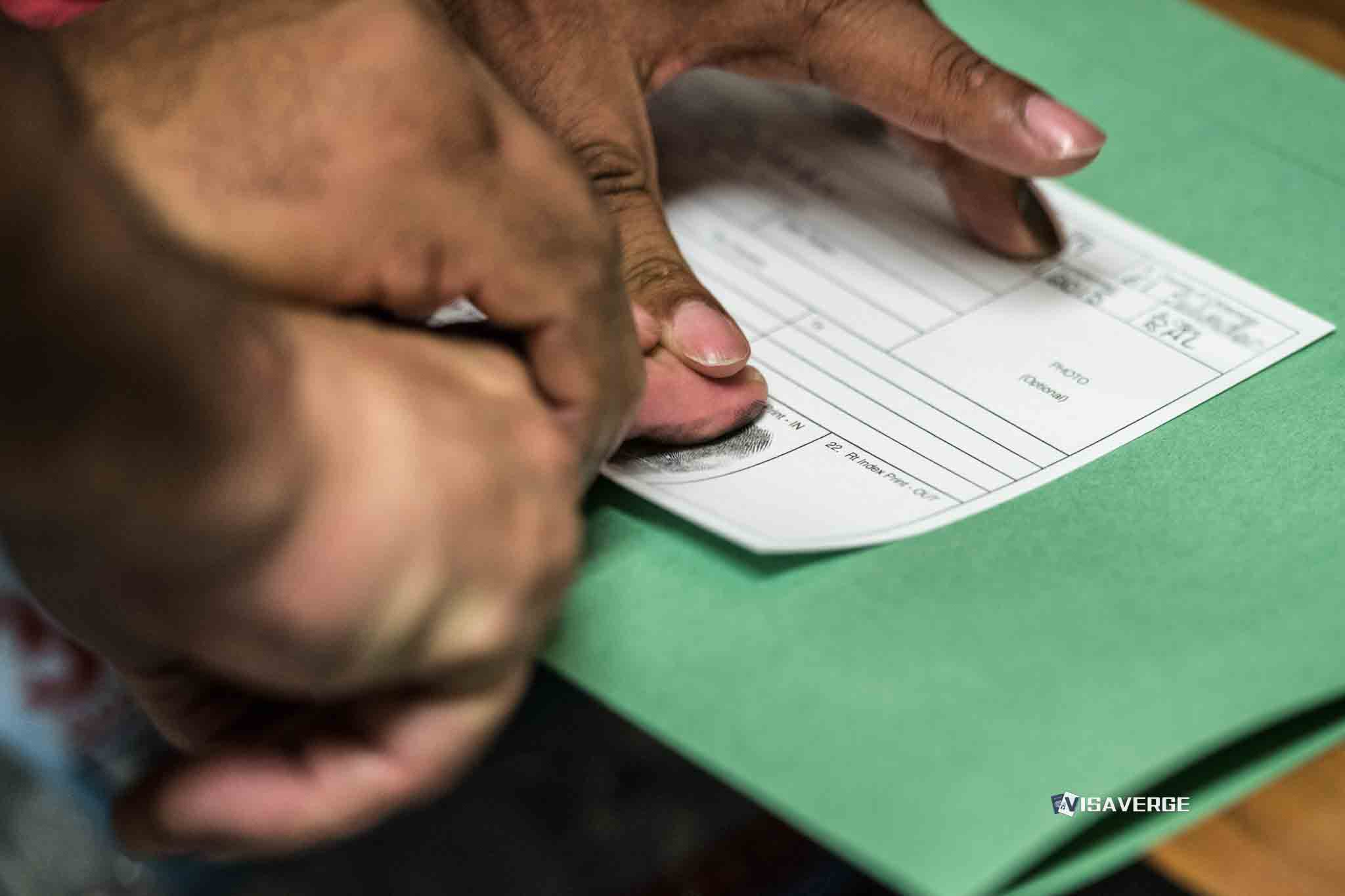

Reverification typically involves a mix of identity and file checks, biometrics, interviews, and interagency comparisons. Below are commonly used reverification steps and the core scope points described by DHS/USCIS.

- Typical reverification steps: Identity checks and file review against prior submissions; biometrics collection (fingerprints/photo) and database checks; interviews to confirm biographical details and travel history; requests for civil documents and identity records; interagency checks that compare information across systems.

- Initial scope: An initial cohort of 5,600 refugees in Minnesota not yet green-carded was identified as the active target group.

- Broader scope stated: DHS has cited 233,000 refugee approvals from January 2021 to February 2025 as part of the stated review objective that could expand if similar patterns are found.

Interactive tools and dashboards are planned separately to show the detailed scope and geographic rollout. This section is written to introduce the program and its potential reach; the interactive tool will provide the structured, visual breakdown of cohorts and timelines.

Section 4: How this can affect refugees who haven’t received green cards yet (and their pending processes)

Refugee admission and a green card are related but separate steps. A person can be admitted as a refugee, live and work lawfully in the U.S., and later file to adjust status to lawful permanent residence. That later step creates a new review moment. USCIS may revisit parts of the record while deciding the green-card application.

A reverification initiative can intersect with that process in several ways. Biometrics appointments may be scheduled or re-scheduled. Interviews may become more common. Officers may ask for documents that were hard to obtain during overseas processing, such as birth certificates, marriage records, or identity papers from countries with weak registries.

Added scrutiny is often triggered by issues like inconsistencies, missing documents, travel history discrepancies, and identity document problems. Any contact from the government can become part of the record that USCIS reviews later.

- Inconsistencies across forms, even small date differences

- Missing civil documents or late-submitted replacements

- Travel history discrepancies, including unexplained trips

- Identity document problems, such as multiple spellings or dates of birth

Contact from the government can take different forms. Some people receive written notices requesting evidence or scheduling an interview. Others may be approached by agents connected to enforcement operations.

✅ For refugees with pending status: keep copies of all notices and prepare for potential additional documentation requests; update documents promptly; attend scheduled appointments.

Section 5: Asylum adjudications and rule changes: pauses, tighter vetting, and expanded ineligibility grounds

Asylum and refugee processing are different pathways. Refugees are processed through the refugee program abroad before admission. Asylum seekers ask for protection after arrival or at the border. Even so, shared anti-fraud priorities and interagency checks can influence both systems.

Reports of a halt or slowdown in asylum decisions since late November 2025 point to a process shift: cases may sit while new vetting standards are rolled out. A pause does not deny a case by itself, but it can extend work authorization timelines, delay interviews, and increase uncertainty for families and sponsors.

A second shift is formal and dated. DHS and DOJ announced a final rule on December 29, 2025 that expands bars for people who pose security or public health risks. “Bars” are legal ineligibility grounds. A broader bar can mean a person who once would have been eligible may now face a threshold denial, or heavier screening before an officer reaches the merits of the claim.

Practically, tighter vetting tends to mean longer waits for interviews and decisions, more RFEs and follow-up questioning, and more denials based on eligibility thresholds or discretion.

Section 6: Legal challenges and court orders: what a temporary restraining order does (and doesn’t) do

Enforcement-heavy programs often trigger litigation. In U.H.A. v. Bondi, plaintiffs described detentions at work and at home, plus lack of notice. Those allegations go directly to due process concerns and how arrests are carried out.

A temporary restraining order (TRO) is short-term emergency relief from a court. It is not a final ruling on the full legality of a program. It usually pauses specific conduct while the court considers next steps, such as a preliminary injunction.

On January 29, 2026, Judge John Tunheim in U.S. District Court issued a TRO tied to Minnesota. The order reportedly blocked federal agents from arresting lawful refugees in Minnesota who had not been charged with specific crimes. Court orders like this can be narrow, time-limited, and fact-specific.

Jurisdiction matters: a TRO in one district may not control practices elsewhere. Class definitions matter as well, because protections may apply only to people who fit the plaintiff group.

Documenting interactions can protect rights without obstructing lawful processes. Keep notices. Write down dates, names, and what was asked. Ask for paperwork that explains the reason for any interview or request.

Section 7: Community impact: fear, compliance pressures, and how to reduce case disruption

Reports from resettled communities describe fear and a chilling effect, especially when legal status holders believe prior approvals can be reopened. That fear can create real risk: people skip appointments, avoid updating addresses, or lose track of documents that later become essential.

Risk points for lawful refugees often look mundane: missed USCIS notices because an address was not updated, lost copies of old applications or identity records, inconsistent records across agencies, and failure to appear for biometrics or interviews.

- Missed USCIS notices because an address was not updated

- Lost copies of old applications or identity records

- Inconsistent records across agencies and time periods

- Failure to appear for biometrics or interviews

Simple steps can reduce disruption. Update addresses with USCIS when required. Keep a dedicated folder with every USCIS notice and filing receipt. Save copies of passports, travel documents, and civil records. Choose a trusted contact who can check mail if travel becomes necessary.

Showing up matters. Missing an appointment can create avoidable complications, even when the underlying case is strong.

Section 8: Where to verify updates and track next steps

Official updates are the safest anchor when rules and enforcement practices are shifting quickly. USCIS posts public announcements through the USCIS Newsroom at https://www.uscis.gov/newsroom. Policy changes that affect adjudications may also appear in the USCIS Policy Manual at https://www.uscis.gov/policy-manual.

Court actions can change what officers and agents may do on the ground. When litigation is active, readers may also monitor filings and announcements through DOJ resources at https://www.justice.gov, especially for major injunctions or nationwide guidance.

A tight enforcement posture from the Department of Homeland Security, paired with post-admission reverification, means one practical takeaway: treat every USCIS notice, interview, and document request as time-sensitive, and confirm instructions only through official channels before responding.

YMYL: This article discusses immigration policy and legal processes. Readers should consult official sources and/or qualified legal counsel for personalized guidance.