- ICE has reportedly purchased warehouses near Clint to create a massive 8,500-detainee facility.

- The proposed project would exceed the 5,000-detainee capacity of nearby Camp East Montana.

- Federal agencies have not yet issued formal announcements regarding construction or operational timelines.

(EL PASO COUNTY, TEXAS) — ICE has purchased warehouses near Clint and plans to convert them into detention facilities with space for 8,500 detainees—far beyond the 5,000-detainee capacity at Camp East Montana—yet ICE and DHS have not issued a formal agency announcement.

Section 1: ICE plan for new detention facilities in El Paso County, TX

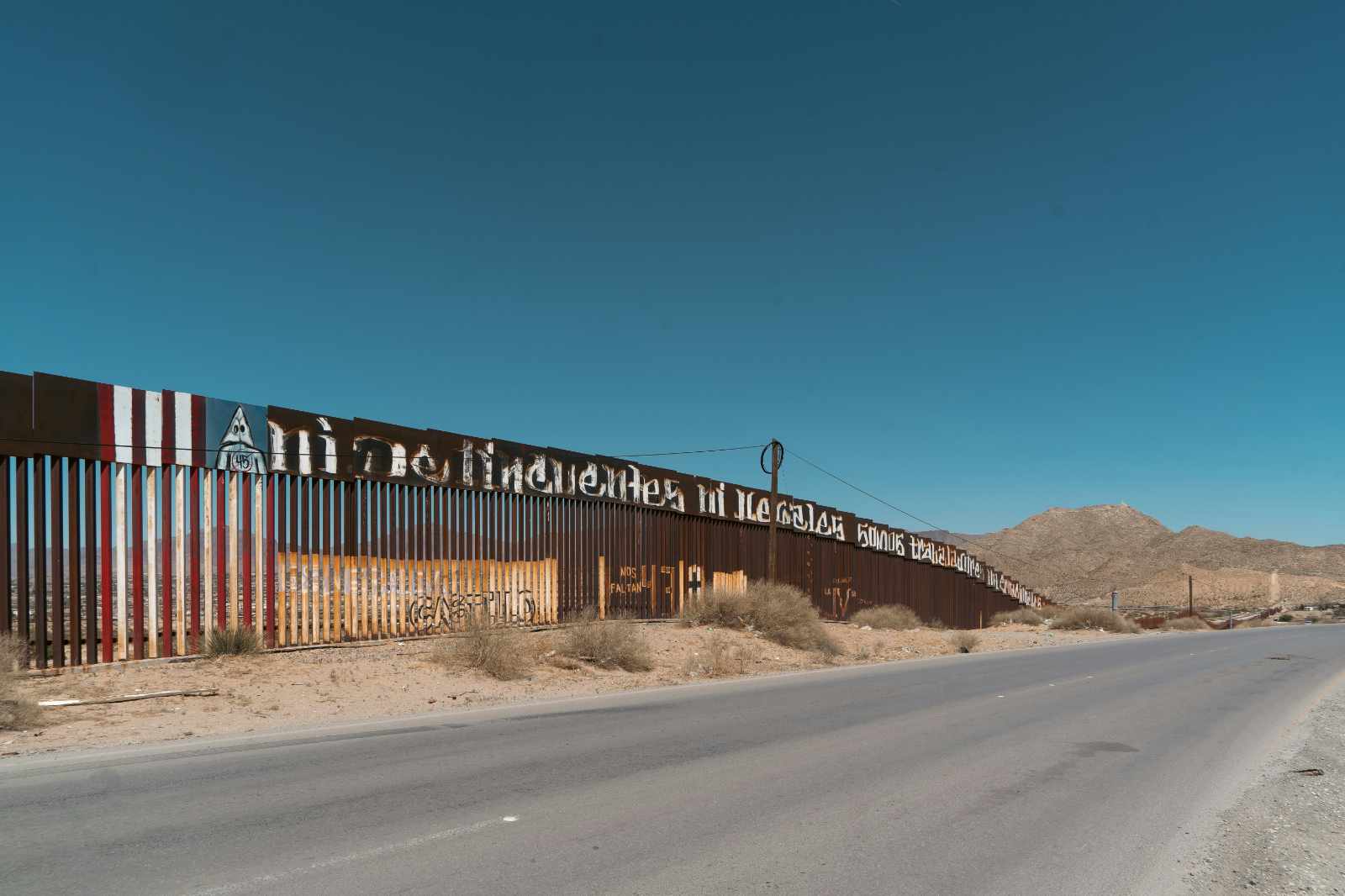

Reports describe a major detention buildout in El Paso County, Texas, tied to warehouses ICE says the federal government purchased on Northeast Wind Avenue. The properties sit between I-10 and Darrington Road, a location that matters because it shapes day-to-day detention operations.

Proximity affects transport routes, emergency response times, and how quickly attorneys, families, and medical providers can reach a facility. In detention, “capacity” is more than a bed count. Beds are the visible number, but real capacity also depends on staffing levels, transportation capacity, medical access, and court access.

Court access can mean physical transport to immigration court or remote hearings that still require secure rooms, interpreters, and reliable connectivity. If any one of those pieces lags, a facility can look “large” on paper but strain in practice. Simple math does not run a detention system.

ICE, through a spokesperson, described the warehouses as planned “very well-structured detention facilities meeting our regular detention standards,” and said they will not operate as warehouses. That statement signals intent to convert industrial space into detention facilities, but it is not the same as a formal agency announcement with a timeline, contractor details, or an opening date.

⚠️ No formal ICE/DHS announcement has been issued; treat figures and plans as reported, not confirmed

Section 2: ICE statements and funding context

ICE’s public messaging pairs two ideas: enforcement priorities and expanded detention space. In the same set of statements, ICE said DHS conducts law enforcement activities nationwide and is “actively working to expand detention space.”

ICE also said it targets “the worst of the worst,” and cited a statistic that 70% of ICE arrests involve noncitizens charged or convicted of U.S. crimes. That kind of language frames enforcement as public-safety driven, even when the operational story is about buildings, contracts, and staffing.

A key line from the spokesperson response creates tension: ICE indicates planning and expansion activity, while also saying, “We have no new detention centers to announce at this time.” Readers should treat that as a distinction between (1) a spokesperson confirming activity and (2) the agency issuing a formal, public-facing announcement.

Agencies often reserve “announcement” for a packaged release that includes scope, contracting method, and implementation steps. A spokesperson statement can confirm pieces of a plan without committing to a final project.

Funding context also matters, but it needs plain language. Detention growth typically requires appropriations, contracts, and service agreements. Coverage has tied this planned expansion to the One Big Beautiful Bill, described as enabling ICE to expand detention space so people can be detained “before they are removed.”

That is a funding concept, not a facility blueprint. A bill name or funding stream does not, by itself, confirm when a specific site will open.

Section 3: Comparison to existing detention capacity

Scale is the headline here. A proposed 8,500-detainee capacity would exceed the region’s largest current facility, Camp East Montana at Fort Bliss, which is described as holding 5,000 detainees. That difference is not just a bigger number; it can change how the region functions for detention logistics.

Large facilities tend to increase transport volume. More detainees can mean more frequent moves for court, medical care, and transfers to other detention facilities. Attorney access can also tighten if visiting rooms, confidential phone lines, and legal mail systems do not expand at the same pace.

Operationally, a very large site can also increase contractor reliance. Food service, medical care, mental health services, and internal transportation may be provided through layered contracts. Oversight then becomes more complex, because accountability can be split among federal monitors, private operators, and subcontractors.

| Facility | Current Capacity (detainees) | Proposed Capacity | Operational Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warehouses on Northeast Wind Avenue (near Clint) | N/A | 8,500 detainees | More transport demand; higher staffing needs; greater pressure on medical, mental health, and legal access systems; larger oversight footprint |

| Camp East Montana (Fort Bliss) | 5,000 detainees | N/A | Existing benchmark for scale in the region; scrutiny increases as population rises and services must keep pace |

Section 4: Local political context and concerns

Veronica Escobar, the congresswoman representing the area, has criticized detention conditions and the public cost of detention operations. Her comments have pointed directly to Camp East Montana, which she described as a $1.24 billion privately operated immigration detention facility funded by American taxpayers.

She has also relayed detainee concerns that include lack of medication access, retaliation, and other issues. Those concerns connect to standard oversight touchpoints such as facility inspections that review sanitation, food service, use of force, grievance systems, and medical care workflows.

Medical access oversight often focuses on intake screening, chronic care follow-up, medication continuity, and emergency escalation procedures. Contractor performance, when a private operator is involved, is also a central question. What gets measured gets managed, but only if monitoring is consistent and findings are acted on.

Community stakeholders typically push for accountability through several channels. City and county meetings may surface local impacts like traffic patterns, emergency response loads, and public health coordination. Congressional offices can request briefings, press for records, and refer issues to inspectors general.

Public records requests may also reveal contracting and property details over time, even when federal agencies limit what they publish proactively.

Section 5: Recent deaths at Camp East Montana

Recent deaths at Camp East Montana have added urgency to questions about health and safety in detention facilities. Victor Manuel Diaz, 36, died on January 14, 2026. Reports described the death as a presumed suicide, under investigation.

Geraldo Lunas Campos, 55, a Cuban national, died on January 3, 2026.

When a death is “under investigation,” it typically means multiple reviews may occur at once. A medical examiner process can involve autopsy findings, toxicology, and records review, and those steps can take time. Separately, a facility may conduct an internal incident review.

Federal oversight bodies may also review whether required checks, referrals, or emergency responses happened on time. Timelines vary, especially when records come from several entities.

Multiple incidents in a short period can intensify scrutiny of mental health screening, suicide prevention practices, medication continuity, and access to urgent care. Those are operational systems that either function every day or fail in predictable ways when staffing and demand do not match.

Section 6: Official confirmation status and sourcing

Readers trying to track this plan should separate “reported planning activity” from “official confirmation.” Official confirmation usually looks like a formal ICE or DHS press release, a published statement on an official agency site, or an identifiable contracting notice.

In many cases, procurement records or contracting documents offer the earliest paper trail. Property records can also confirm ownership changes, even when an agency stays quiet.

Spokesperson statements sit in the middle. An on-the-record spokesperson can confirm specific facts, such as the purchase of warehouses or an intent to convert them into detention facilities. Yet a spokesperson can also limit what they confirm, as shown by the statement that ICE has “no new detention centers to announce at this time.”

That can mean the project is still being finalized, contracted, or reviewed. It can also mean the agency is not ready to publish a full announcement with details.

Future updates often surface in practical ways: local permits, construction activity, contract awards, inspection activity, congressional inquiries, or litigation filings. Each has different weight. A permit may show a project is advancing, but not who will run it.

A contract award can identify operators and service providers. An inspection report can show what standards are being applied once a facility is operating.

✅ Check official DHS/ICE press releases and public procurement records for formal confirmations and contracting notices

⚠️ No formal ICE/DHS announcement has been issued; treat figures and plans as reported, not confirmed

For readers affected by detention logistics, one more distinction helps: this is about ICE detention capacity, not USCIS case processing. Still, expanded capacity can affect real-world timing for detainee movement, attorney access, and transportation to hearings.

When confirmation is incomplete, those timelines are harder to predict. Checking for formal notices is a practical step, especially for families trying to locate someone or attorneys planning visits. USCIS information remains available, but it is not the primary channel for ICE detention facility announcements.

This article discusses detention facilities and government actions; information may evolve as agencies release official statements. Readers should verify updates with official sources.

Not legal advice. For individual rights and relief options, consult qualified counsel.