- The Fourth Amendment protects individuals from unreasonable searches and seizures during immigration enforcement encounters.

- Administrative warrants like Form I-205 do not grant entry to private homes without specific consent or exigency.

- USCIS is expanding its armed enforcement footprint through the creation of new Special Agent roles.

The core right: In the United States, people generally have the right to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures, including unreasonable force by government officers. This protection comes primarily from the Fourth Amendment, and it often matters most during home encounters and arrests.

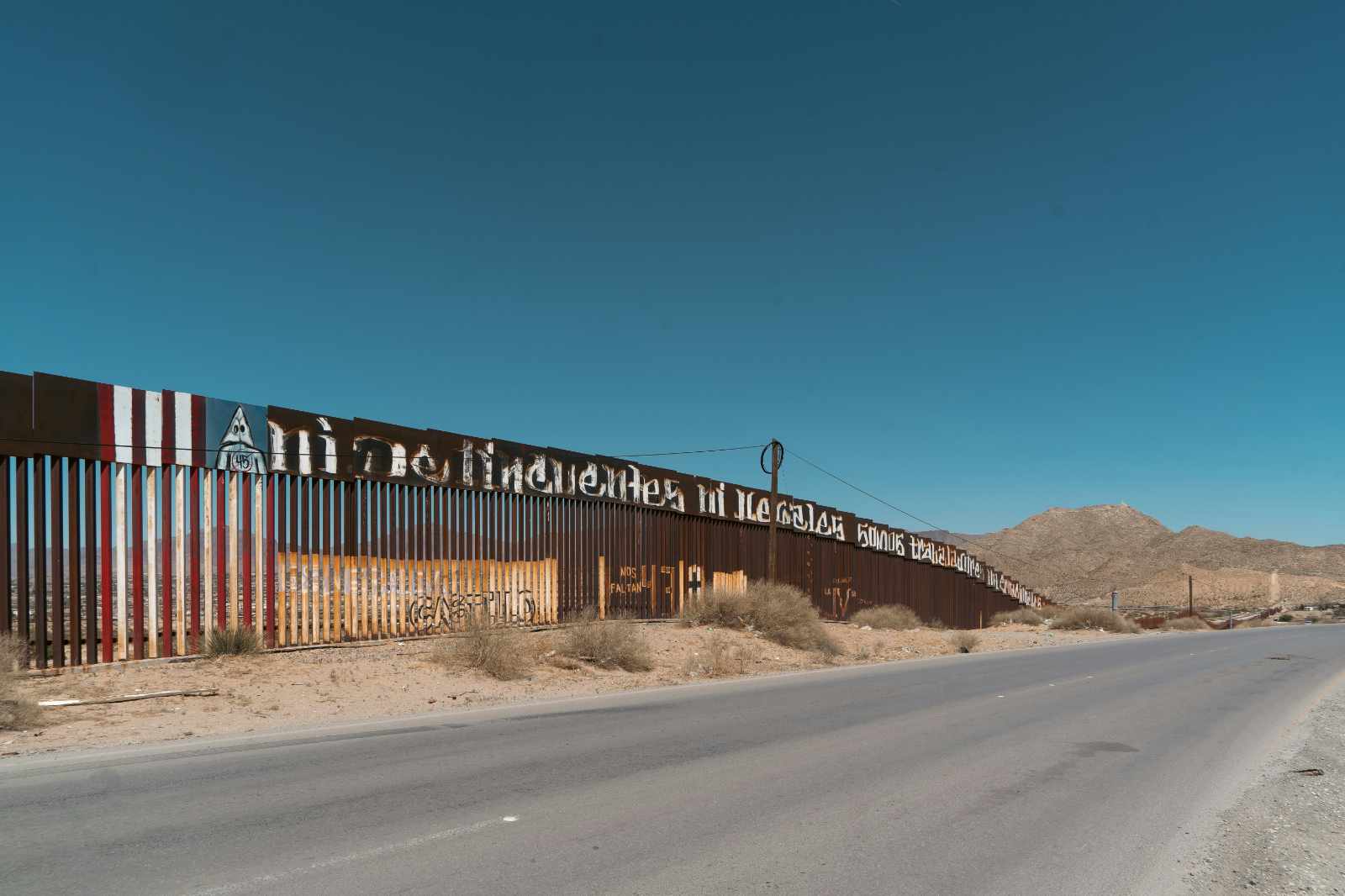

Recent public attention has focused on federal immigration enforcement, including whether officers may rely on administrative warrants—and what “reasonable” or “necessary” force means in practice when an encounter escalates. These questions affect safety, legal strategy, and the risk of accidental waiver of rights.

Who’s who in immigration enforcement (and why overlap happens)

- ICE (DHS): Interior enforcement, arrests, detention, and removals.

- CBP (DHS): Border and ports-of-entry enforcement, including searches at airports and land crossings.

- USCIS (DHS): Immigration benefits (green cards, naturalization, work authorization). USCIS may also issue certain charging documents and coordinate with enforcement in some cases.

- EOIR (DOJ): Immigration courts, where Immigration Judges decide removal cases.

These roles can overlap. A person may go to USCIS for a benefits interview, face an enforcement referral, and later deal with ICE custody and EOIR court.

Administrative vs. judicial warrants (plain language)

A judicial warrant is signed by a judge or magistrate and is tied to Fourth Amendment warrant rules.

An administrative immigration warrant is typically issued within the executive branch, not by a judge. A commonly referenced form is Form I-205.

Why it matters: The U.S. Supreme Court has long treated the home as a highly protected place. Under Payton v. New York, 445 U.S. 573 (1980), non-consensual entry into a home to make an arrest generally requires a warrant, absent consent or exigent circumstances. How that rule applies when the government presents an immigration “administrative warrant” is part of the current legal and policy dispute.

Warning: Opening the door and letting officers inside can be treated as consent. Consent may reduce later arguments that an entry was unlawful.

This guide provides general information on rights in these encounters and how to exercise them carefully.

Official Statements: What DHS Leadership Is Saying Publicly

Public messaging from senior officials can shape enforcement posture, but it does not replace the Constitution, statutes, or regulations. It also may not describe how every field office acts on the ground.

In recent public statements, DHS leadership has emphasized a more assertive enforcement posture, including messaging about lower border encounters and claims of operational success. DHS public affairs messaging has also addressed criticism of home-entry practices by asserting that individuals targeted by administrative warrants have already received due process in immigration court and have final removal orders.

These statements matter for two reasons:

- Operational signals: Public remarks can suggest priorities, staffing, and tactics, including how aggressively officers may pursue arrests.

- Limits of what quotes prove: A quote cannot, by itself, establish that a practice is lawful. The legal standard comes from the Fourth Amendment, federal statutes, federal regulations, and controlling case law. Internal DHS or ICE memos can also be challenged if they conflict with higher authority.

If you are evaluating a claim you saw online, treat official quotes as one data point, not the legal rule itself. Confirm the underlying legal authority and any written policy that is actually in effect.

Key Facts and Policy Mechanics: Administrative Warrants, Use of Force, and USCIS’s Enforcement Expansion

Administrative warrants and Form I-205

Form I-205 is commonly referred to as an administrative warrant of removal/deportation. It is not the same as a court-issued warrant. In many encounters, officers may present an I-205 to show they have authority to take someone into immigration custody.

Arrest authority in immigration law: INA § 287 (8 U.S.C. § 1357) and related regulations authorize certain DHS officers to make immigration arrests under defined conditions. Standards governing officer conduct include 8 C.F.R. § 287.8, which addresses, among other topics, arrests and use-of-force principles.

“Necessary and reasonable force”

In many law-enforcement settings, “necessary and reasonable” force means force that is proportionate to a legitimate purpose, given the facts known at the time. The constitutional backstop is generally the Fourth Amendment “objective reasonableness” standard for seizures. See Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386 (1989).

When disputes arise, the key questions often include whether the person was actually seized, whether the force was proportionate to the perceived threat, and whether there were safer alternatives that were feasible at the time.

The “Lyons Memo” concept (as reported)

Reporting has described an internal ICE memo authorizing officers to use force to enter a residence relying on an administrative warrant for people with final removal orders. Conceptually, this raises a direct legal tension with home-entry doctrine under Payton and related cases like Steagald v. United States, 451 U.S. 204 (1981) (limits on entering a third party’s home to execute an arrest warrant).

Whether such a policy is lawful in a specific setting can depend on facts, location, consent, exigency, and controlling circuit precedent.

USCIS special agents and what that signals

USCIS has historically been a benefits adjudication agency. Recent developments include a final rule creating USCIS “Special Agents” in the 1811 criminal investigator series, with firearms and arrest authority. Operationally, this signals an expanded enforcement footprint around benefits work.

Why readers should care: Even if most USCIS appointments remain routine, a more enforcement-oriented posture may increase fear around interviews and heighten the stakes of any inconsistency or past contact with law enforcement.

Quick context, briefly stated: Publicly reported figures include 32 confirmed deaths in ICE custody in 2025, officer shootings involving at least nine people across five states between September 2025 and January 2026, and over 50,000 applications for the new USCIS enforcement roles as of late 2025.

Significant Incidents and How Narratives Get Contested

High-profile incidents can become focal points for policy change, litigation, and public debate. They also produce competing narratives early on.

The Renee Nicole Good shooting (publicly disputed accounts)

The fatal shooting of Renee Nicole Good, a U.S. citizen, during an enforcement operation has been described differently by federal authorities, local officials, and bystander video interpretations. In many such cases, key facts are contested in the first days and weeks, including positioning, perceived threat, and the sequence of commands.

It is important not to treat early accounts—on any side—as final. Legal conclusions about justification, civil liability, or criminal liability typically depend on full evidentiary development.

Whistleblower disclosures and constitutional questions

Whistleblower disclosures about home-entry practices and training materials can raise constitutional concerns. They may also become evidence in congressional oversight, agency investigations, or litigation. At the same time, not every disclosure proves a practice is widespread, and not every allegation is legally accurate.

A practical way to assess evolving claims is to separate published documents from summaries or secondhand accounts, look for the text of memos, rulemaking records, and court filings, and track whether an agency confirms, rescinds, or revises guidance.

Warning: Do not assume that an “administrative warrant” allows officers into your home. Ask whether they have a judicial warrant signed by a judge, and avoid giving consent.

Impact on Immigrants, Families, and Communities: What Changes in Practice Can Look Like

How practice changes may show up day-to-day

- Reduced willingness to report crimes or cooperate as witnesses.

- Missed medical visits, school events, or worship services due to fear of enforcement presence.

- Heightened anxiety around check-ins, ankle monitors, and routine appointments.

Home encounters: why the “warrant” label matters

Many people assume any “warrant” allows entry. That is not always true. A judicial warrant is different from an administrative immigration warrant.

If officers lack a judge-signed warrant, they may still attempt entry through consent (someone opens the door and lets them in), exigent circumstances (a narrow concept that depends on immediate emergency facts), or entry into common areas of some multi-unit buildings, depending on local law and building layout.

USCIS interviews, benefits filings, and NTA anxiety

USCIS’s enforcement posture can affect how people perceive routine benefits processing. One recurring fear is that a denied application or a discovered issue may trigger a charging document in removal proceedings.

Notices to Appear (NTAs) are governed by INA § 239 and related rules, and they initiate immigration court proceedings in EOIR.

Quick context, briefly stated: Reports indicate USCIS has issued over 196,600 NTAs since early 2025. Even when a person may have defenses, the process itself can be destabilizing.

Legislative response: H.R. 7119 (proposal, not automatic law)

A proposed bill titled the “Stop Excessive Force in Immigration Act” has been introduced with ideas such as body cameras, training standards, and stricter warrant practices for home entries. A bill does not change your rights unless it is enacted and implemented. Always confirm whether a proposal became law.

Deadline: If you are arrested, ask immediately to speak with an attorney. Early decisions can affect bond, defenses, and deadlines in immigration court.

How to Exercise These Rights—and What to Do If Rights Are Violated (Plus Official Sources)

Who has these rights?

- U.S. citizens: Full Fourth and Fifth Amendment protections.

- Lawful permanent residents (LPRs): Same constitutional protections inside the U.S.

- Visa holders and other lawful residents: Same baseline protections inside the U.S.

- Undocumented immigrants: Fourth and Fifth Amendment protections generally apply inside the U.S., though remedies can be limited in immigration court.

At or near the border, CBP has broader search authority, and Fourth Amendment rules operate differently. Expect more limited privacy in routine inspections.

How to exercise rights during an encounter (practical steps)

- Stay calm and ask who they are. Ask if they are ICE, CBP, USCIS, or local police.

- Do not open the door. Speak through the door if you can.

- Ask for a judicial warrant. Ask them to slide it under the door or hold it up to a window.

- Check the warrant carefully. Look for a judge’s name, court, address, and your correct name.

- Do not consent to entry or search. Say, “I do not consent to entry or a search.”

- Use the right to remain silent. You can state your name in some jurisdictions, but you can decline detailed questions.

- Ask for a lawyer. If detained, say you want to speak with an attorney.

Warning: Signing documents without fully reading them can waive rights. This may include stipulated removal, voluntary departure paperwork, or interview statements.

Common ways rights get waived or lost

- Consent by conduct: Stepping aside and letting officers in can be treated as consent.

- Statements made under pressure: Casual explanations can be used later.

- Sharing documents: Giving passports, IDs, or immigration papers without advice can shift the encounter quickly.

- Missing court dates: Failing to appear can trigger an in-absentia order and long-term consequences.

If you believe rights were violated

- Write down details immediately: Names, badge numbers, agency, time, location, witnesses, and what was said.

- Preserve evidence: Keep videos, screenshots, doorbell camera footage, and medical records.

- Request records: An attorney may advise a FOIA request for documents.

- Consider complaints: Depending on the facts, complaints may be made to DHS oversight offices. An attorney can help assess risk and strategy.

Official sources to check (and how to use them)

Use primary sources to confirm what is real and current.

- DHS press statements and policy messaging: DHS Newsroom — Best for official statements, leadership comments, and announcements.

- USCIS updates and rule announcements: USCIS Newsroom — Best for benefit-related policy updates and USCIS operational changes.

- Aggregate force data at the border: CBP use-of-force stats — Best for high-level reporting and trend context, not case-by-case verification.

When comparing claims, match them to an actual posted release, a published rule, or a verified dashboard entry. Save copies and dates.

Legal help resources

- AILA Lawyer Referral: AILA Find a Lawyer

- Immigration Advocates Network (nonprofit directory): Immigration Advocates Network (nonprofit directory)

⚖️ Legal Disclaimer: This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.