(WASHINGTON) — The Dignity for Detained Immigrants Act (H.R. 6397) proposes a new legal and oversight framework that would, if enacted, change who DHS may detain, where detention may occur, and how release decisions are made—issues that matter most to people in ICE custody, their families, detention operators, and the lawyers and providers who support them.

Introduced on December 3, 2025, by Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) and Rep. Adam Smith (D-WA), the bill sits at the center of a broader dispute over detention authority, public safety messaging, and the scale of federal enforcement.

Supporters describe the current system as inhumane and argue for narrower detention use and stronger oversight. DHS leadership has criticized the effort as weakening rule-of-law enforcement capacity. Those competing frames help explain why the bill’s “process” matters: it would reshape the steps DHS must follow before, during, and after placing someone in immigration detention.

Key terms you’ll see in this guide

- Mandatory detention: Rules that require detention for certain people while removal proceedings are pending, limiting release options. Mandatory detention is commonly associated with INA § 236(c).

- Alternatives to detention (ATD): Non-custodial supervision tools such as check-ins, case management, or electronic monitoring.

- Private detention / for-profit detention: Detention space operated by private contractors, and in some models, county jails used under paid agreements.

- Vulnerable populations: Categories such as certain caregivers, asylum seekers, and people with serious illnesses, as described in the proposal.

This guide uses several legal and programmatic terms consistently; see the definitions above to follow the steps below.

The proposed “process” under H.R. 6397—step by step

What follows is a practical walkthrough of how detention and release decision-making would likely work if H.R. 6397 became law. It is contrasted with current practice at key points.

Because legislation can change during committee work and amendments, readers should treat these steps as a process explainer—not a guarantee of future procedures.

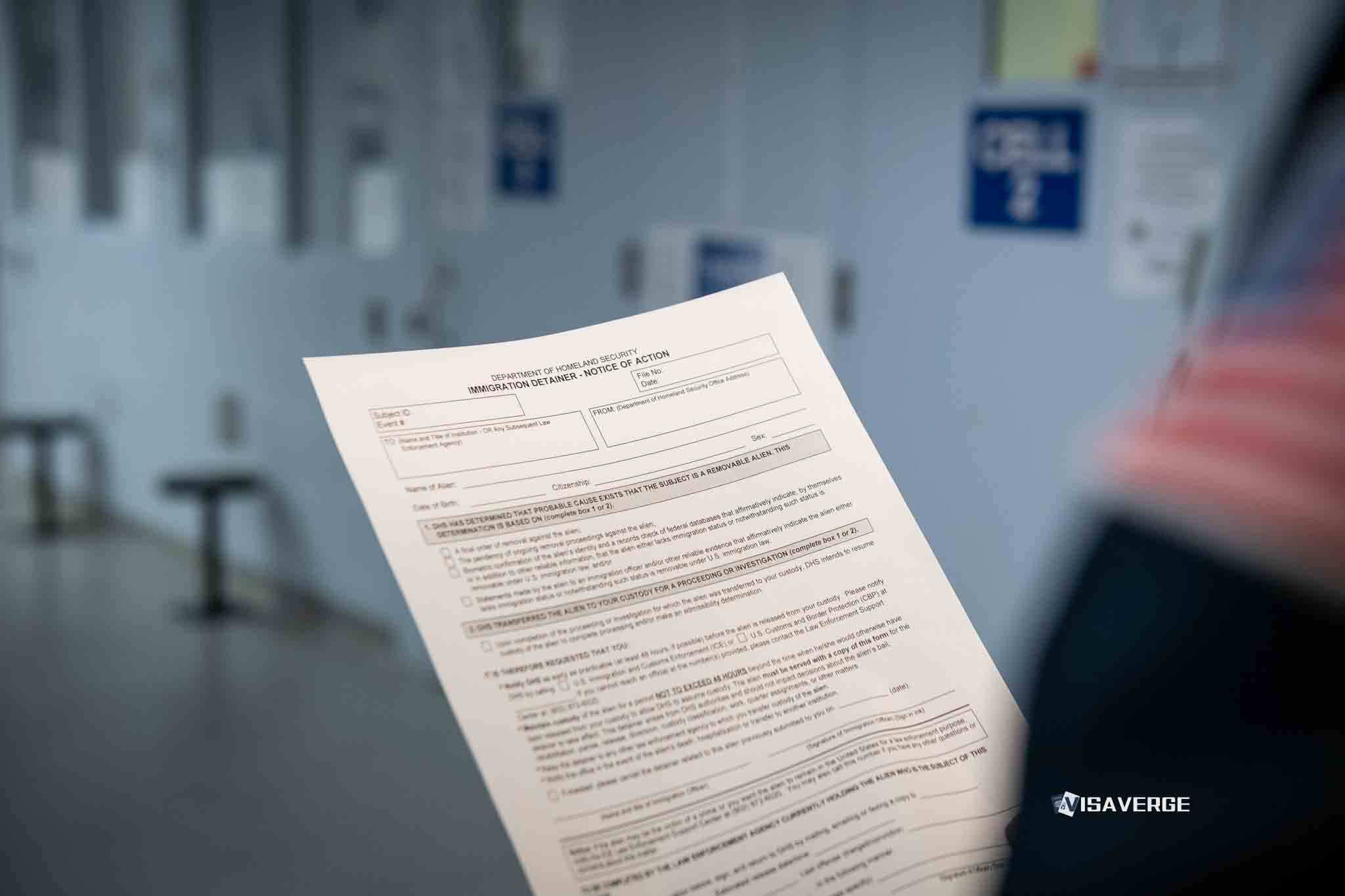

1) Confirm the custody basis and charging documents

What happens now: Many people first learn the legal basis for custody when ICE issues a charging document and files it with Immigration Court.

If H.R. 6397 were enacted: This step still matters, but it becomes more important because the bill would narrow when detention is required versus discretionary.

Documents to request/keep:

- Notice to Appear (NTA) (initiates removal proceedings)

- I-286, Notice of Custody Determination (common ICE custody decision notice)

- Any bond paperwork (when applicable)

- Medical intake notes if the person has a serious illness

Decision point: Whether the person is treated as subject to mandatory detention now often shapes whether an Immigration Judge can consider bond. Under current law, mandatory detention disputes frequently involve INA § 236(c) and related litigation that can vary by circuit.

Warning: Do not assume bond is available. Eligibility depends on the custody statute ICE applies and the court’s jurisdiction.

2) Screen for “vulnerability” and urgent medical needs

What the bill changes: H.R. 6397 would create a presumption of release for specified vulnerable groups, including certain caregivers, asylum seekers, and people with serious illnesses. A presumption typically means the default outcome is release unless the government shows a legally sufficient reason to detain.

Documents to prepare:

- Medical records (diagnoses, medications, treatment plans)

- Proof of caregiver status (birth certificates, custody orders, school/medical records)

- Proof of address and community ties (lease, bills, letters from community or faith leaders)

Healthcare angle: For detained people with significant medical needs, documentation often determines whether release, transfer, or accommodations are considered. Even if H.R. 6397 is not enacted, timely medical records can be important for custody requests, humanitarian arguments, or detention-condition complaints.

3) Evaluate whether detention is legally required—or discretionary

What happens now: Mandatory detention rules can remove bond discretion in many cases. Where bond is available, ICE or an Immigration Judge may set conditions.

What H.R. 6397 proposes: A repeal or major limit on mandatory detention for certain categories. Practically, that would shift more cases into a discretionary release framework, where individualized factors matter more.

Documents that typically matter in discretionary custody decisions:

- Criminal case dispositions (certified records are best)

- Evidence of rehabilitation (program completion, letters)

- Proof of stable employment or family support

- Prior immigration history documents (prior orders, prior appearances)

Decision point: Even under a more release-oriented framework, cases involving alleged danger or flight risk would likely remain contested. Outcomes may vary depending on how DHS implements standards and how courts interpret the statute.

4) Choose the placement pathway: detention bed vs. ATD vs. release

What H.R. 6397 targets: The bill would phase out private detention facilities and certain for-profit county jail usage over time, raising practical questions about where people would be held during any transition.

What “family detention” means: Holding parents and children in custodial settings while immigration cases proceed. H.R. 6397 would prohibit detention of families and children, which would likely push DHS toward release, ATD, or non-detention placements.

Documents for ATD/release planning:

- Sponsor/support affidavit letters

- Verified home address and contact plan

- Transportation plan for court and check-ins

Warning: Missed check-ins or incorrect addresses can trigger re-detention or in absentia consequences in Immigration Court.

5) Trigger oversight mechanisms and document conditions

What changes under the bill: H.R. 6397 would require unannounced inspections by the DHS Office of Inspector General and allow Members of Congress unannounced access for oversight. This contrasts with policies that require advance notice for facility visits.

A DHS policy memorandum dated January 8, 2026, stated that facility visit requests must be made seven days in advance, with shortened time requiring approval by the Secretary.

What detainees and counsel should document:

- Dates and details of medical requests and responses

- Grievances filed with the facility

- Names/titles of staff involved, when available

- Photos or copies of written requests, when permitted

6) Litigate custody and proceed with the underlying case

Even if detention rules change, the removal case continues under EOIR procedures: Immigration Court → BIA → federal circuit courts. Detention status can affect the pace of hearings and access to counsel.

Core filings and documents that often run on parallel tracks:

- EOIR change-of-venue motions (if released to another state)

- Asylum application Form I-589 (for those seeking asylum, withholding, or CAT)

- Requests for prosecutorial discretion (policy-dependent)

- Bond motion packets (where available)

Relevant legal standards: Asylum is under INA § 208. Withholding is under INA § 241(b)(3). CAT protection arises under federal regulations implementing treaty obligations, often litigated alongside I-589-based claims.

7) Prepare for timelines—and likely delay points

Typical timing varies widely. Legislation, if enacted, may include implementation dates and transition periods. Operational delays often come from contracting changes, staffing, and new guidance issuance.

Case-level delays often come from court backlogs, transfers between facilities, or medical evaluations.

Common delay points include:

- Waiting for medical records or expert evaluations

- Transfers that interrupt attorney access and document exchange

- Disputes over custody authority (mandatory vs. discretionary)

Key provisions of H.R. 6397 in plain English

H.R. 6397 would, in broad strokes, do four things:

- Reduce or eliminate mandatory detention categories, increasing individualized release decision-making.

- Phase out private detention and for-profit jail arrangements, which could shift detention geography, contracting, and bed availability.

- End family and child detention, likely increasing reliance on release, ATD, or community placement models.

- Create presumptive release for vulnerable groups and strengthen oversight through unannounced inspection and access rules.

Because legislative text and implementation guidance can evolve, the real-world effect would depend on appropriations, DHS rulemaking or directives, and how courts interpret any new statutory language.

Detention scale and funding: why it drives the debate

Detention population size affects conditions, medical access, legal visitation, and the feasibility of meaningful oversight. It also influences how heavily DHS relies on ATD tools.

As of December 2025, ICE reported over 66,000 individuals in custody. Advocates citing publicly discussed data have argued that nearly 73% of detainees have no criminal convictions, though definitions differ across datasets.

“No convictions” can exclude pending charges, non-conviction arrests, or immigration-only offenses, so readers should verify methodology.

Funding is also central. A mid-2025 appropriations measure described as allocating about $170 billion to DHS included $45 billion tied to expanding detention capacity, with a reported target of over 100,000 beds.

Capacity expansion can conflict with reforms aimed at reducing reliance on detention, unless release standards and ATD infrastructure expand in parallel.

Timeline and why late-2025/early-2026 events matter

Confirmed facts: H.R. 6397 was introduced December 3, 2025, by Jayapal and Smith. DHS issued public responses criticizing reform efforts, and a DHS memorandum dated January 8, 2026, set a seven-day advance notice rule for facility visit requests.

Political positioning (interpretation, not law): The bill is being framed by supporters as a human-rights and oversight measure, and by DHS leadership and enforcement-first allies as undermining enforcement capacity.

A notable incident cited in public reporting is the January 7, 2026, fatal shooting of Renee Nicole Good in Minneapolis involving an ICE officer, followed by renewed calls for reform and funding leverage statements by progressive lawmakers.

As of date: This guide reflects the public status and statements available Wednesday, January 21, 2026.

Stakeholder impacts if enacted

Detainees and families: May see more release eligibility, more ATD use, and stronger inspection pressure on facilities. Outcomes would still depend on risk assessments and implementation details.

Healthcare and service providers: Could see higher demand for medical documentation, discharge planning, and community-based care coordination if more people are released.

DHS and local partners: Would face transition questions around contracts, bed space, transportation, and concerns about absconding or public safety messaging.

Oversight bodies: Unannounced access may increase transparency. DHS may raise operational and security objections, particularly at facilities with safety protocols.

Official sources and how to track status

To verify what is proposed versus what is currently binding law:

- Bill text and actions: Congress.gov is the best primary source for sponsors, amendments, and legislative actions.

- DHS statements: The DHS Newsroom posts official messaging and releases, which can explain agency positions but is not law.

- USCIS updates: USCIS covers immigration benefits, not detention operations, but changes can affect eligibility and filings.

To confirm whether anything has changed since January 21, 2026, check the “Latest Action” and “Tracker” sections on Congress.gov and compare against DHS Newsroom postings and any Federal Register notices.

Common mistakes that can derail release efforts

- Missing deadlines for filing or renewing address information with EOIR after release

- Submitting incomplete medical records or unsigned provider letters

- Relying on unofficial criminal-history summaries instead of certified dispositions

- Failing to document caregiver responsibilities with verifiable records

Because detention, bond eligibility, and removal defense can turn on small facts and circuit-specific law, attorney review is often decisive for complex cases.

This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.

Resources

– Immigration Advocates Network