- Immigration bond hearings are critical time-sensitive defenses for seeking release from detention in Cleveland and Ohio.

- The DHS has recently intensified interior enforcement with new policy memorandums and expanded search-warrant authorities.

- Successful bond hearings require strong evidence of ties to the community and a lack of flight risk.

(CLEVELAND, OHIO) — One of the most time-sensitive defenses after an ICE arrest is seeking release from detention through an immigration judge bond hearing (also called a “custody redetermination”). In Cleveland and across Ohio, that strategy can buy critical time to prepare a removal defense, protect family stability, and avoid rushed decisions based on fear or rumors.

This guide explains what is confirmed from official DHS, ICE, and USCIS statements; what is being reported locally; and how people in Northeast Ohio can assess risk and respond lawfully if ICE contact occurs. It also outlines the legal standards for bond, the evidence that tends to help, and common barriers.

Because detention moves fast and mistakes are hard to undo, attorney representation is often decisive.

1) Overview: intensified interior enforcement and local concerns

Cleveland-area immigrant communities have reported heightened anxiety tied to broader interior enforcement messaging from DHS and ICE, plus localized reports of door knocks and arrests. Some information is confirmed in official releases. Other claims circulate through social media without details that can be verified.

A practical approach is to separate: (1) official announcements with dates and legal authority, from (2) neighborhood reports that may be incomplete or mischaracterized. This article helps readers do three things: spot policy signals that can increase day-to-day risk, identify personal factors that affect detention and bond, and use reliable channels to verify claims before acting.

2) Official statements and policy updates (dates and actions)

Federal announcements can change practical risk even without visible “raids.” They can affect officer posture, screening, and how aggressively DHS uses existing authorities.

Based on the cited official materials, the key dated items include:

- Jan. 1, 2026: A USCIS policy memorandum (PM-602-0194) directing adjudicative holds on certain pending cases for “enhanced review.”

- Jan. 16, 2026: A DHS final rule expanding authority for USCIS 1811 special agents, including arrest and search-warrant execution authority.

- Jan. 20, 2026: A DHS recap statement emphasizing removals and self-departures, framed as stepped-up enforcement.

- Jan. 21, 2026: A DHS press statement describing an increased “self-deportation bonus,” paired with a warning about arrest and future return.

- Jan. 3, 2026 (reported): ICE messaging about a major hiring increase, which can affect encounter frequency.

When you read official releases, focus on three items: the scope (nationwide or limited), the effective date, and the implementation details (who is covered, and what changes operationally). Broad language can still translate into narrower practice. But it can also change screening and detention choices quickly.

3) Key facts, statistics, and policy details (and what they mean in practice)

“Operations” and early numbers

A named operation such as “Operation Buckeye” typically signals resource concentration, target lists, and coordinated arrest activity. Early arrest figures are often a snapshot. They do not reliably predict long-term patterns in Cleveland neighborhoods.

If staffing increases are real, more officers can mean more workplace leads, more home follow-ups, and more scrutiny of pending filings. It can also increase the speed of custody decisions after arrest.

Administrative warrants vs. judicial warrants at the door

Many Cleveland families ask a simple question: “Do we have to open the door?”

- A judicial warrant is signed by a judge or magistrate. It usually identifies a place to be searched or a person to be arrested.

- An administrative immigration warrant is typically issued within DHS. It is not signed by a judge.

In many cases, an administrative document alone does not authorize entry into a home without consent. The distinction matters most at the front door. The safest general practice is to stay calm, ask to see paperwork, and seek legal advice immediately.

Warning: Do not lie or present false documents. False statements can trigger criminal exposure and long-term immigration consequences, even for people with possible relief.

“Self-departure incentives” and misinformation risk

Programs framed as “self-deportation” or voluntary departure incentives can be misunderstood. Any choice to depart can affect: unlawful presence bars, pending applications, and future eligibility to return.

You should confirm terms through official sources and counsel before acting.

4) Context and local responses in Cleveland

Cleveland-specific signals have been mixed, and that is common in fast-moving enforcement periods.

Local reporting has described door-knock encounters on the West Side. Some law offices have said they received multiple credible reports. At the same time, the Cleveland Division of Police (CDP) has publicly stated it does not enforce federal immigration law and has not confirmed “raids.”

Both statements can be true. CDP may not participate, while federal officers still operate. Also, door-knock stories can be hard to confirm because families fear reporting, and paperwork is not always shared.

Public walkouts and protests, including student actions, reflect fear and community mobilization. They also show why accurate verification matters. A rumor can cause families to skip school, work, or medical care, even when the local facts are unclear.

For credible local updates, many families rely on established legal aid providers and reputable nonprofits that publish know-your-rights materials and do not traffic in rumors.

5) Impact on affected individuals and communities (and lawful preparedness)

Real-world disruption

Heightened enforcement fear can reduce participation in daily life. Families may avoid groceries, school meetings, and clinics. Local businesses can also see reduced foot traffic.

These community-level effects can be significant even when enforcement is uneven.

Pending cases can be affected

People with pending asylum, family petitions, or adjustment cases may fear that any DHS contact will derail the process. In reality, outcomes vary by status, criminal history, and procedural posture.

USCIS “holds” or enhanced review can delay adjudications. In some cases, delays intersect with detention decisions if a person is arrested by ICE and placed in removal proceedings. Timing can matter.

Safety basics without “evasion”

Preparedness is not hiding. It is planning.

- Keep copies of key documents in a safe place.

- Identify an emergency contact and childcare plan.

- Memorize at least one phone number.

- If approached, ask if you are free to leave. If detained, ask to speak to counsel.

Deadline: Bond hearings and motions can move quickly after arrest. Families should contact an immigration attorney as soon as possible, ideally within the first 24–72 hours.

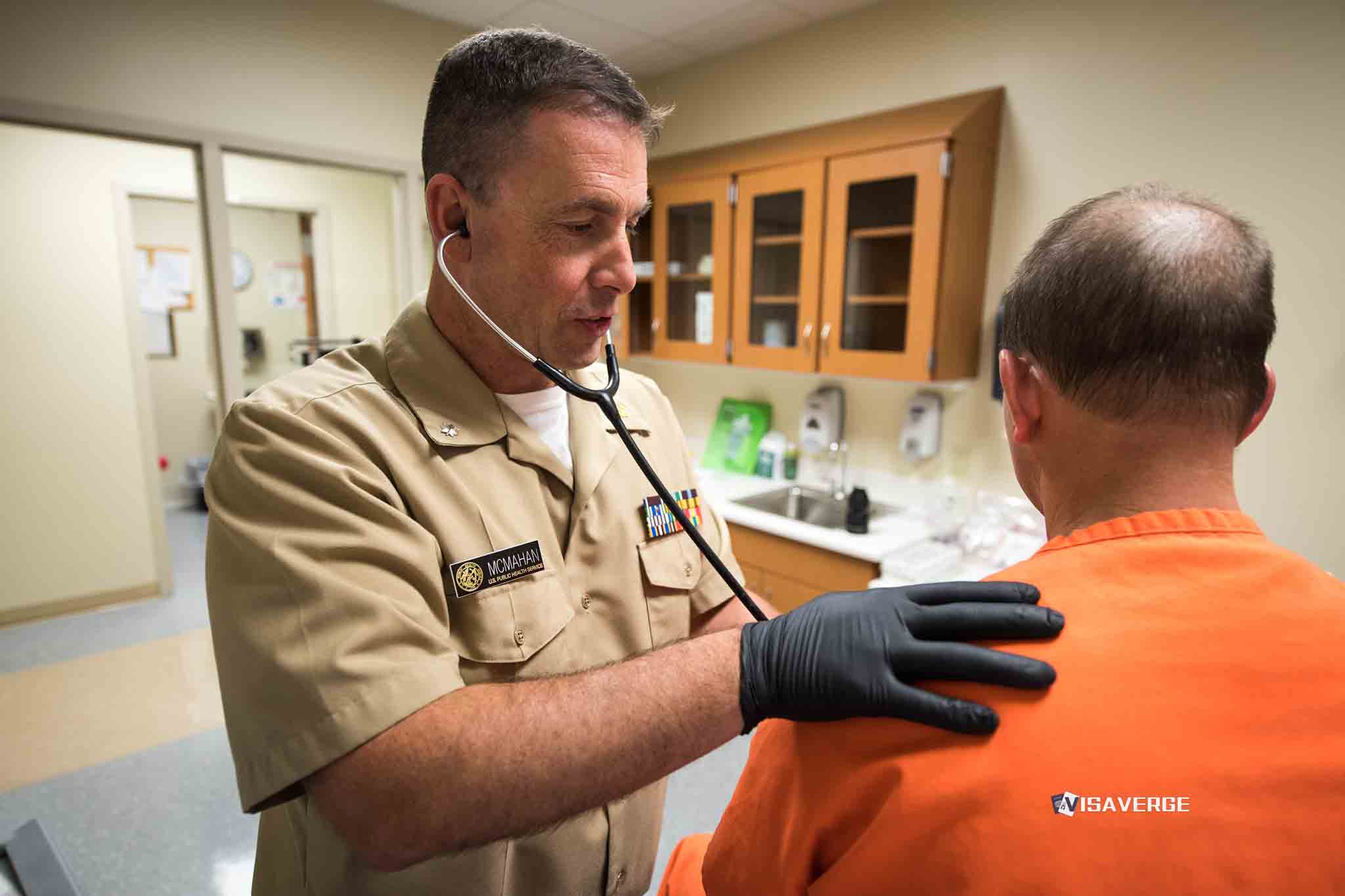

6) Defense strategy: bond and custody redetermination after an ICE arrest

The legal framework

Most ICE detainees in Ohio will face one of two custody regimes:

- Discretionary detention with bond eligibility under INA § 236(a). Immigration judges generally have authority to set bond. See 8 C.F.R. § 1236.1 and 8 C.F.R. § 1003.19.

- Mandatory detention for certain categories, often tied to specified criminal grounds, under INA § 236(c). If mandatory detention applies, bond may be unavailable from the immigration judge.

At a bond hearing, the judge focuses on two core questions: danger to the community and risk of flight. A leading Board decision is Matter of Guerra, 24 I&N Dec. 37 (BIA 2006), which discusses the types of factors immigration judges weigh.

Evidence that typically helps

The strongest bond packets are organized and specific. Common helpful items include:

- Proof of long-term residence in Cleveland or Ohio.

- Family ties, including U.S. citizen or permanent resident relatives.

- Stable work history and employer support letters.

- Proof of address and community involvement.

- Documentation resolving or mitigating criminal issues.

- A concrete plan to appear in court, including transportation and reminders.

If there is criminal history, records matter. Judges and ICE look closely at dispositions, not rumors. Certified docket entries and final judgments can be important.

Factors that strengthen or weaken cases

Strengtheners often include: no serious criminal history, long residence, strong family responsibilities, consistent past compliance with court, and a viable form of relief.

Weakeners often include: recent entries, prior removal orders, prior failures to appear, allegations of gang involvement, or unresolved charges.

Disqualifiers and bars

Bond may be blocked by mandatory detention categories, certain criminal grounds, or reinstated removal orders. Some people can request a bond hearing and learn that the judge lacks jurisdiction.

Also, an old removal order can trigger rapid removal. That can shrink the window to file motions.

Warning: If you have a prior removal order, do not assume you will get a standard court timeline. Speak with an attorney immediately about motions to reopen, stays, and eligibility for screening.

Outcome expectations

Bond outcomes vary widely by facts, charges, and the assigned court’s practices. Many Cleveland-area cases turn on documentation quality and whether the person has a clear relief strategy. No attorney can promise release.

But represented detainees often present stronger records and clearer legal arguments, which can affect both bond and the underlying case posture.

7) Official sources and where to verify information

When policies and operations shift quickly, official sources matter because they provide precise language, dates, and scope. Before relying on claims about “new rules,” verify directly through official announcements and policy libraries.

Start with the DHS newsroom, the ICE newsroom, USCIS policy memoranda, and EOIR’s immigration court information. Confirm any memo number, form reference, or “effective immediately” claim in the original source. If you cannot find it, treat it as unconfirmed.

Because people can misread documents at stressful moments, consider having an attorney review any paperwork shown by officers and any charging documents issued by DHS.

Legal resources

– USCIS policy memoranda: https://www.uscis.gov/laws-and-policy/policy-memoranda

– EOIR immigration court info: https://www.justice.gov/eoir

Resources:

⚖️ Legal Disclaimer: This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.