- Students in Bryan, Texas launched protests following immigration enforcement activity occurring near local school communities.

- DHS officials rescinded the protected areas policy allowing for increased enforcement visibility near sensitive locations.

- Legal experts emphasize the difference between administrative warrants and judicial warrants signed by a judge.

(BRYAN, TEXAS) — A key legal and policy shift shaping today’s school-based protests took effect when DHS rescinded its 2021 “Protected Areas” guidance on January 20, 2025, and the change is now colliding with a renewed DHS surge of interior immigration enforcement tied to Texas operations on January 19, 2026.

Students at Bryan High School began protesting this week after Monday’s immigration enforcement activity in their area. While the protest is local, it reflects a wider national reaction to heightened enforcement visibility, fear of family separation, and uncertainty about what limits remain near schools during a DHS surge.

1) Background of the Bryan High School protest

Bryan High School, in Bryan, Texas, saw student protests as reports spread of a multi-agency operation on Monday, January 19, 2026. The immediate trigger was community perception that arrests and related enforcement activity disrupted families connected to the school community.

In many cities, protests arise quickly after visible enforcement events. Arrests at homes, traffic stops, or workplaces can ripple into school attendance the next morning. Students often report classmates “disappearing” after a parent is detained. Even when the person arrested is not a student, the household impact can be immediate.

The Bryan High School protest also fits a broader national trend. When federal agencies announce increased interior operations, communities often react before they know the operational facts. That gap between messaging, law, and lived experience can drive demonstrations.

2) Official DHS statements and framing

DHS officials have publicly framed the enforcement posture as targeted and safety-driven.

Assistant DHS Secretary Tricia McLaughlin stated on January 22, 2026, that ICE “did NOT target a child” in a widely discussed incident elsewhere. She said officers remained with a child “for the child’s safety” while agents arrested the father.

In a separate January 16, 2026 statement, she emphasized that ICE is “not going to schools to arrest children,” while also stating that criminals should not be able to “hide” in schools to avoid arrest.

Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem said on January 20, 2026, that DHS is focusing on “serious criminals” and that CBP will support ICE operations against the “worst of the worst.”

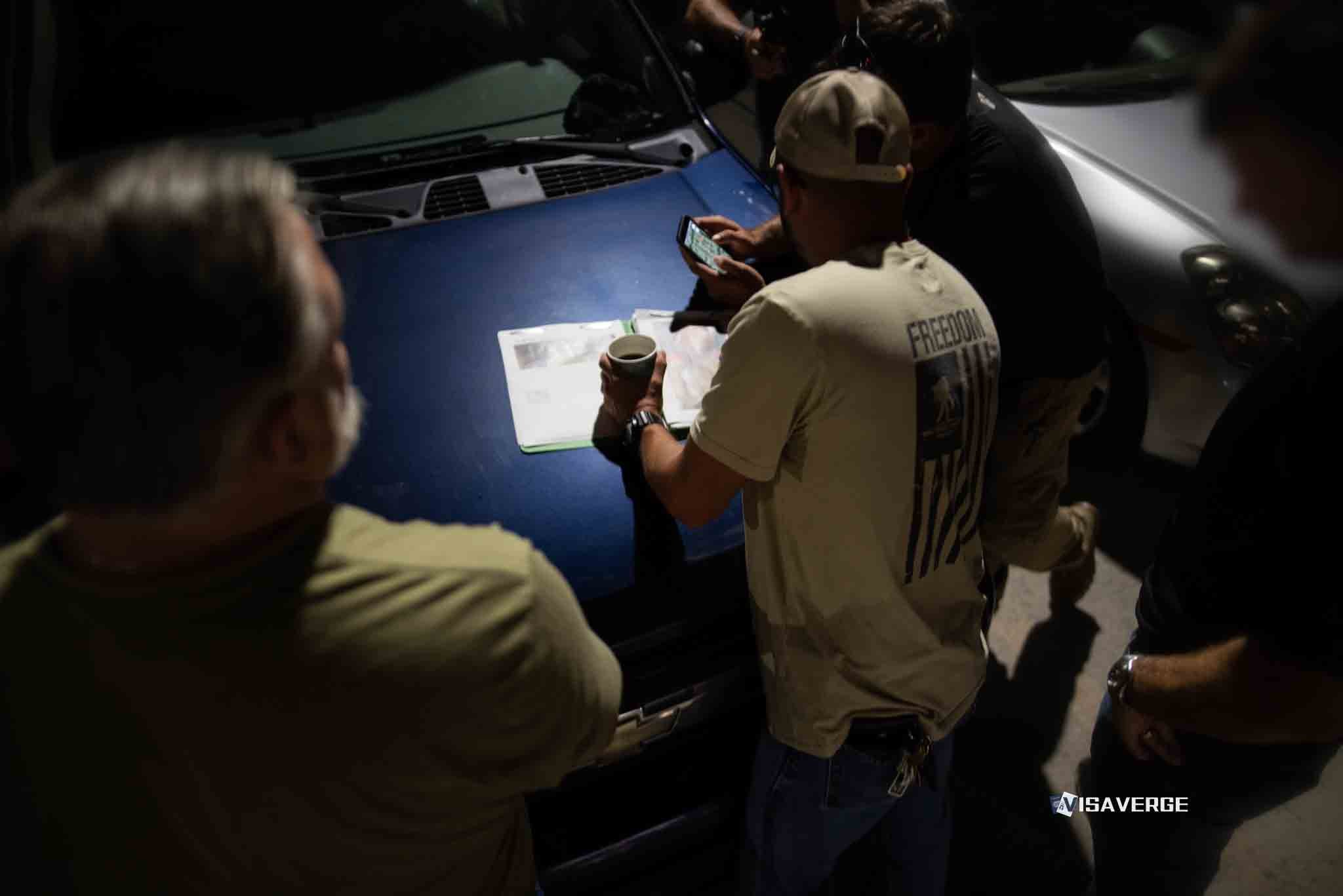

These statements matter, but readers should separate broad framing from legal mechanics. Operational details depend on: (1) what authority officers claim at the moment of contact, (2) whether they seek consent to enter, and (3) whether they have a judicial warrant signed by a judge, versus an administrative immigration warrant.

3) Key facts and policy details

Interior surge mechanics

DHS describes coordinated “interior” operations as multi-agency efforts. These may involve ICE, and sometimes coordination with other DHS components. Such operations can span multiple cities, which is consistent with the January 19 activity reported in Texas.

The “Protected Areas” change (conceptual overview)

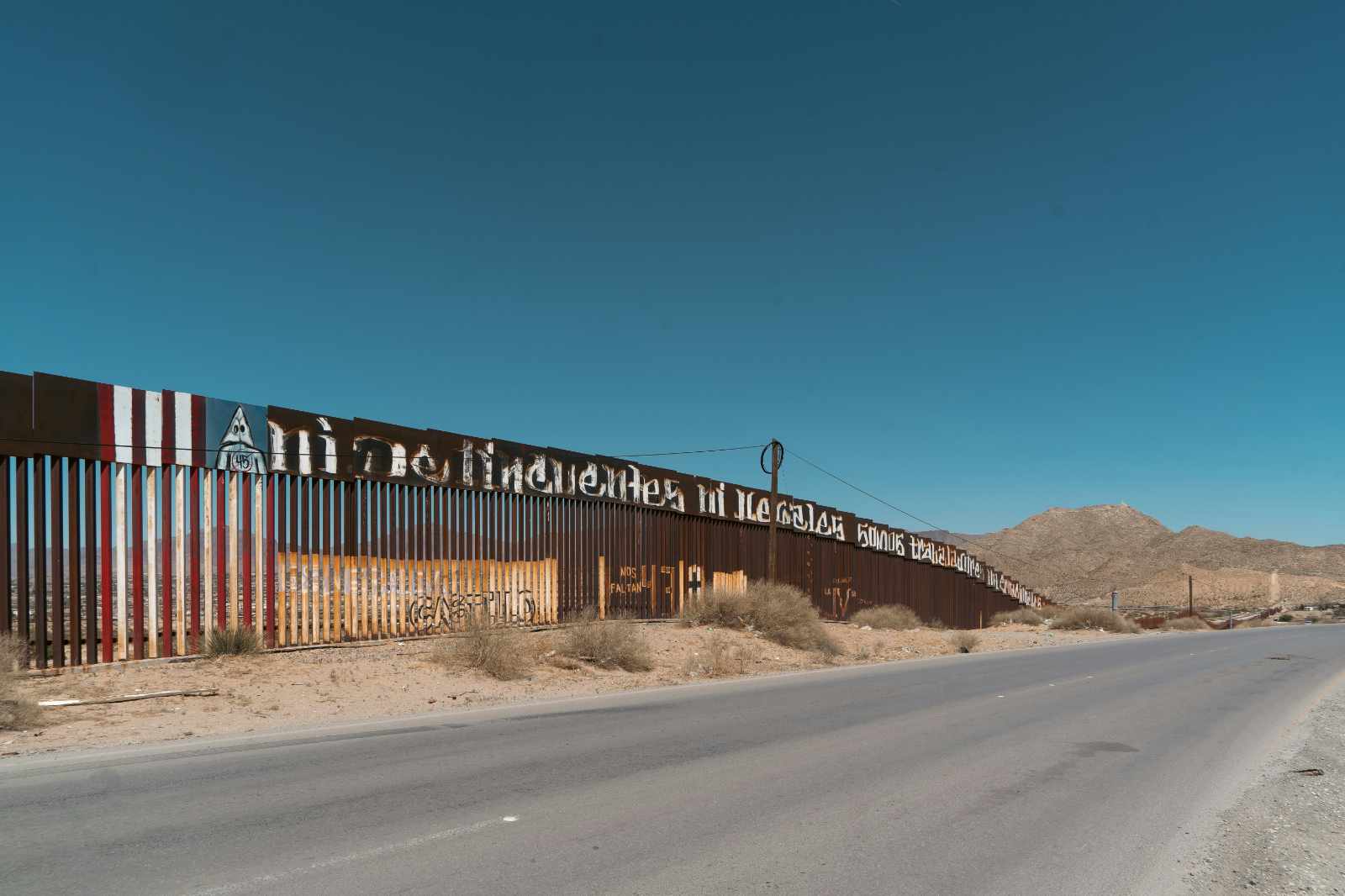

DHS rescinded the 2021 “Protected Areas” guidance on January 20, 2025. Practical effect: there is no longer a bright-line internal policy discouraging enforcement near sensitive locations like schools, churches, or hospitals.

This does not mean “anything goes.” The Constitution still constrains searches and seizures. State and local school rules can also control campus access. But the rescission may increase the perceived risk of enforcement activity near places families rely on daily.

Administrative vs. judicial warrants (plain-language)

A critical distinction in many home encounters is the type of “warrant” presented:

- Judicial warrant: Signed by a judge or magistrate. It can authorize entry into a specific place, within limits.

- Administrative immigration warrant: Typically issued within DHS. Examples include Form I-205. It is generally used to authorize immigration arrest procedures, but it is not signed by an Article III judge.

A whistleblower disclosure described a May 12, 2025 memo reportedly authorizing residential entry using only an administrative warrant. DHS has defended the use of administrative warrants as longstanding in immigration enforcement.

As a legal baseline, courts have long held that warrantless home entry is heavily restricted. Consent and exigent circumstances are recurring issues in litigation. See, e.g., Payton v. New York, 445 U.S. 573 (1980) (home entry limits in criminal context).

Immigration enforcement adds statutory layers, including arrest authority under INA § 287 and related regulations at 8 C.F.R. § 287.8.

What families may experience in practice includes “knock-and-talk” encounters, questions at the door, requests to come inside, and rapid transfers after arrest. Documentation of names, agencies, and paperwork shown may become important later in bond, custody, or removal defense.

Warning: An administrative immigration warrant is not the same as a judge-signed warrant. Whether officers may enter a home can turn on consent, the document shown, and the facts at the door.

4) Context and significance of related incidents

Other high-profile incidents are shaping community reaction, including in places far from Bryan.

Liam Ramos incident (alleged): Reports describe a 5-year-old detained with a parent in a driveway after returning from school, with an allegation that the child was used as “bait.” DHS disputes child-targeting. These claims, even when contested, can heighten fear and increase absences.

Renee Good shooting (reported): Officials have described the January 7, 2026 fatal shooting of Renee Nicole Good in Minneapolis as connected to threats against agents. Such incidents often bring scrutiny to enforcement tactics, use of force policies, and accountability.

Manpower surge (announced): ICE announced on January 3, 2026 that it hired 12,000 new officers in under a year. Staffing increases can raise the frequency and visibility of operations, which can affect school attendance and protest activity.

5) Impact on affected individuals and communities

Schools often see predictable patterns after visible enforcement events: spikes in absences, parents avoiding drop-off lines, and students reporting stress or panic. Some districts in other cities have shifted to remote learning during periods of high fear, according to reports.

Community concerns may include profiling claims, especially during large operations. Civil-rights groups often respond by setting up hotlines, collecting affidavits, and advising residents to document encounters. Some cases may evolve into broader litigation, including class-action claims, but those outcomes depend on evidence and jurisdiction.

Families also describe transfers that feel sudden. A person may be moved quickly between facilities. That can create information gaps about location, medical needs, and access to counsel.

Deadline: If a family member is detained, ask immediately for the person’s A-number and detention location. Bond requests and court deadlines can move quickly.

6) Official government sources and where to read more

For primary-source verification, readers can check DHS’s Newsroom for official statements and announcements, and ICE press releases for operation summaries and stated priorities. CBP operational statistics can help interpret trends, but they rarely explain a specific local event.

USCIS policy memoranda are useful for benefits adjudications, but they are not the same as ICE enforcement guidance.

When saving official pages, preserve the date, headline, and a PDF print. Web pages can change, and versioning can matter in later disputes.

Warning: Do not rely on social media screenshots alone. Save the official page and record the date accessed.

Recommended actions and timeline

- This week: Families should review emergency contact plans and identify trusted counsel. Schools should review visitor and law-enforcement access protocols.

- If contacted by officers: Ask what agency they represent and what document they are relying on. Do not guess or volunteer information.

- If an arrest occurs: Consult an immigration attorney promptly. Eligibility for relief can depend on criminal history, entry facts, and prior orders, including possible relief under INA § 208 (asylum), INA § 241(b)(3) (withholding), CAT protections, or cancellation under INA § 240A.

Pending challenges are possible, particularly around home entry practices and alleged profiling, but outcomes depend on facts, evidentiary records, and the federal circuit.

Resources:

Legal Disclaimer: This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.