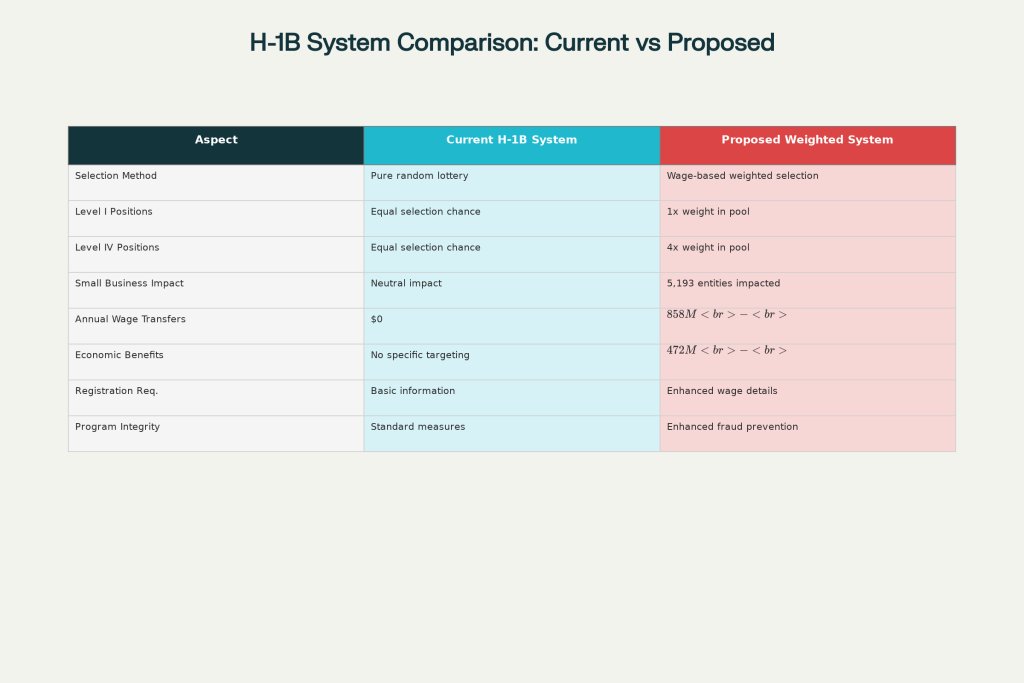

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has issued a proposed rule to overhaul the H-1B visa cap selection process, shifting from today’s random lottery to a weighted selection process that favors higher-paid, higher-skilled foreign workers. Under the current system, when the annual H-1B visa quota is oversubscribed, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) conducts a random lottery giving each registered candidate an equal chance. The new proposal, titled “Weighted Selection Process for Registrants and Petitioners Seeking to File Cap-Subject H-1B Petitions”, would instead give applicants with higher offered wages better odds of being selected, while still preserving some chance for candidates at all wage levels.

The core goal is to align H-1B visa allocations with the program’s original intent – attracting top talent and specialty skills – by rewarding employers who commit to paying higher wages (a proxy for higher skill levels). This article explains the proposed changes, why DHS is pursuing them, how the weighted process would work, and what it means for employers and prospective H-1B workers.

Core Changes: From Random Lottery to Wage-Based Weighting

The Current System Under Fire

For over a decade, the H-1B program has operated under a purely random selection process that critics argue fails to serve Congressional intent. Under the existing system, all qualified registrations enter a computer-generated lottery with equal chances, regardless of the worker’s skill level or salary. This approach has consistently resulted in the lowest representation of highly skilled workers, with wage levels III and IV (representing experienced and fully competent workers) being the least selected in every fiscal year from 2019 through 2024.

Revolutionary Weighted Selection Methodology

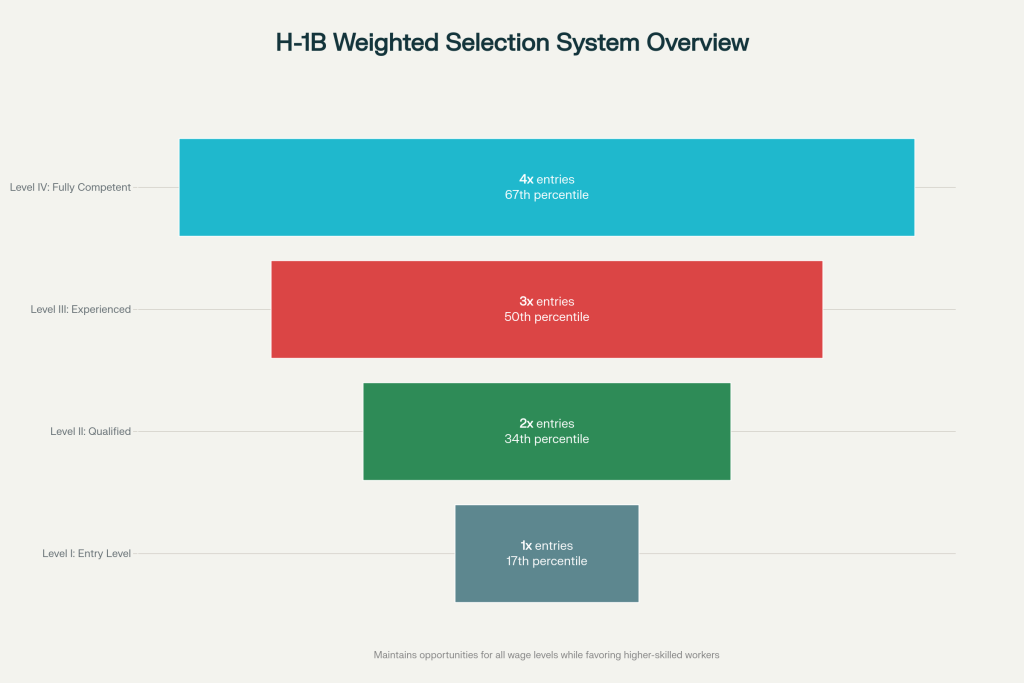

The proposed system introduces a four-tiered weighting structure based on Department of Labor wage level classifications. Rather than eliminating lower-wage positions entirely, the new approach assigns different weights to each category in the selection pool.

The weighting system operates on a simple but powerful principle: beneficiaries assigned to higher wage levels receive multiple entries in the selection pool, dramatically increasing their chances of selection while still preserving opportunities for entry-level positions.

Understanding the Wage Level Framework

The Department of Labor’s Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS) system categorizes positions into four distinct levels based on skill requirements and corresponding wage percentiles:

Wage Level IV represents “fully competent” positions requiring the highest skills, typically at the 67th percentile of wage distribution for the relevant occupation and location. These roles demand extensive experience and specialized expertise.

Wage Level III encompasses “experienced” workers at approximately the 50th percentile, requiring significant background in the field with proven competencies beyond basic qualifications.

Wage Level II covers “qualified” positions at the 34th percentile, suitable for workers who have moved beyond entry-level but haven’t yet reached senior status.

Wage Level I addresses “entry-level” positions at the 17th percentile, designed for workers beginning their careers in specialized fields.

Why Change the H-1B Selection Process?

Challenges with the Current Lottery System

For over a decade, demand for H-1B visas has far exceeded the annual statutory cap (currently 85,000 new visas per fiscal year, including 65,000 general cap and 20,000 for U.S. advanced-degree holders). In recent years, hundreds of thousands of registrations are submitted for these limited slots, making a random lottery the default selection method. This chance-based system has faced criticism for failing to prioritize the most highly skilled or highest paid workers that the H-1B program was designed to attract. Congress created H-1B in 1990 primarily to help U.S. employers fill labor shortages in highly skilled, specialized positions and keep American companies competitive. At the same time, lawmakers imposed a numeric cap and other safeguards to prevent an oversupply of foreign labor from undercutting U.S. workers’ wages.

Under the lottery, many visas have been going to lower-wage, entry-level positions, simply because those make up a large portion of the registrations each year. DHS data indicate that H-1B petitions at Wage Level III and IV (the two highest skill/wage categories) are “the least represented wage levels in H-1B petitions under the current process”. In other words, the random lottery often ends up allocating a disproportionate share of visas to lower-paid workers, contrary to the program’s intent to bring in the “best and brightest” talent. Additionally, the simplicity of the lottery system has invited gaming through mass registrations. In the FY2024 lottery, for example, some individuals were registered by dozens of different companies to multiply their odds. USCIS had to implement a “beneficiary-centric” rule in 2024 to ensure each person gets only one shot regardless of duplicate entries. These integrity concerns and the misalignment of outcomes with program goals underscored the need for reform.

DHS’s Motivation and Goals

Weighted H-1B Selection System – Wage Levels, Definitions, and Selection Odds

| Wage Level | Definition (per DOL/USCIS) | Approx. Percentile in Wage Distribution | Lottery Weighting (Entries in Pool) | Relative Odds (vs. Level I) | Implications Under Proposed Rule |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level I | Entry-level: basic understanding of duties; performs routine tasks under supervision. | ~17th percentile of local occupation wages | 1 entry | Baseline (1x) | Lowest chance of selection. Still possible to be chosen, but share of visas will shrink significantly. Often applies to recent graduates or junior roles. |

| Level II | Qualified: some experience; can perform moderately complex tasks with limited supervision. | ~34th percentile | 2 entries | 2x | Moderate chance of selection, roughly double Level I. Covers workers with a few years’ experience or roles requiring more independence. |

| Level III | Experienced: fully competent, specialized knowledge, significant responsibility. | ~50th percentile (median) | 3 entries | 3x | Strong chance of selection. Expected to see a large increase in visas for this group compared to current system. |

| Level IV | Fully competent/expert: advanced experience, specialized skills, often supervisory or lead roles. | ~67th percentile and above | 4 entries | 4x | Highest odds of selection. Employers offering top-tier salaries gain a major advantage. These cases likely to dominate visa allocations under the new system. |

DHS believes that offering higher wages is a reasonable proxy for higher skill levels or more specialized talent. While not a perfect measure, a job paying at or above the top prevailing wage for its occupation (Wage Level IV) typically requires greater expertise or experience than one paying an entry-level wage. Even if an employer simply chooses to pay above the minimum required wage, DHS reasons that a higher wage offer reflects the employer’s valuation of that worker’s skills and potential contribution. Thus, rewarding higher wage levels in the selection process should channel H-1B visas toward higher-skilled, higher-valued workers, consistent with the H-1B program’s purpose.

The agency also wants to incentivize employers to raise wages or seek more skilled candidates for H-1B roles, and disincentivize using the H-1B program for lower-paid, lower-skilled positions (which some argue should be filled by the domestic workforce or other visa categories). Importantly, DHS has sought to do this without completely shutting out lower-wage petitions. The proposed weighted lottery is presented as a more balanced approach than a strict wage-ranking system: it tilts the odds toward higher wages but “maintain[s] the opportunity for employers to secure H-1B workers at all wage levels”. This reflects a policy judgment that, while prioritizing top talent, the program should remain accessible for varied business needs – including startups or less-paid occupations – as long as the demand exists.

In summary, DHS is proposing the change to better fulfill Congressional intent (filling critical skilled labor gaps and attracting highly skilled workers) and to ensure the limited H-1B slots go more often to the “highest skilled and paid” applicants, thereby boosting the U.S. economy and innovation. The rule is also a response to the record volume of registrations and concerns about fairness in the current lottery system, aiming to inject a merit-based element into the selection process.

Economic Impact and Financial Projections

Massive Economic Transfers and Benefits

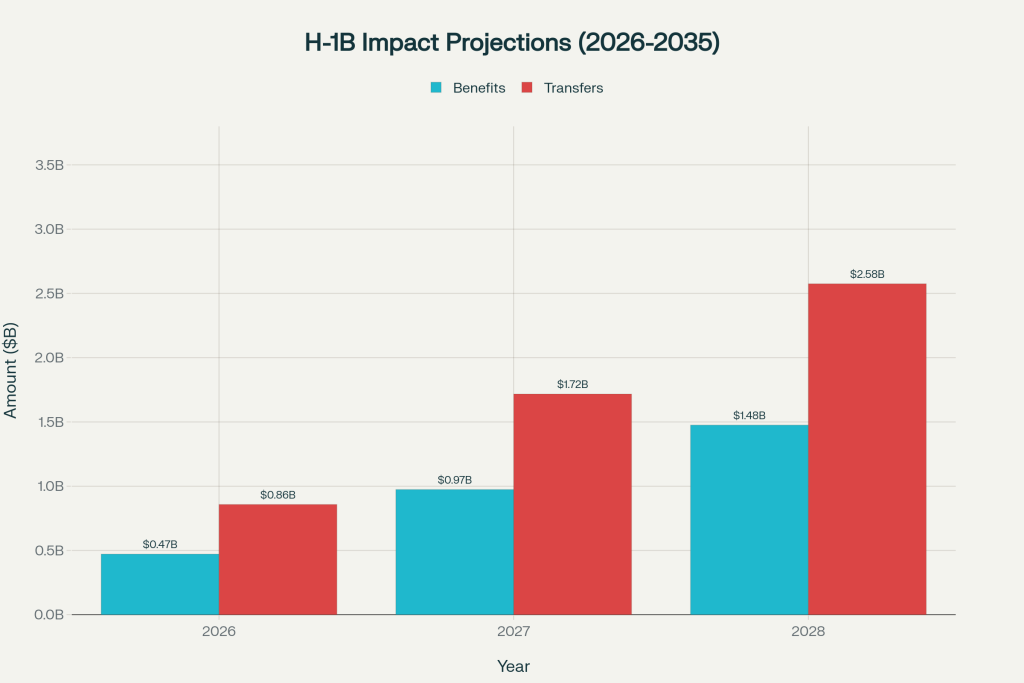

The proposed changes will trigger substantial economic shifts within the H-1B ecosystem, with DHS projecting unprecedented financial transfers and benefits over the 10-year implementation period.

The economic modeling reveals a dramatic escalation in both benefits and transfers, starting at $472 million in annual benefits and $858 million in wage transfers for fiscal year 2026, ultimately reaching $1.978 billion in benefits and $3.434 billion in transfers annually from 2029 onward. These figures represent the largest economic transformation in the H-1B program’s history.

| Fiscal Year | Annual Benefits (millions) | Annual Transfers (millions) | Net Benefits (millions) | Total Cost (millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2026 | $472 | $858 | $472 | $30 |

| 2027 | $974 | $1,717 | $944 | $30 |

| 2028 | $1,476 | $2,575 | $1,446 | $30 |

| 2029-2035 (annual) | $1,978 | $3,434 | $1,948 | $30 |

The comprehensive economic analysis demonstrates how wage transfers will shift from Level I positions to higher-wage categories, fundamentally altering the program’s economic impact. DHS estimates that annual wage transfers will grow from approximately $858 million in fiscal year 2026 to $3.4 billion annually by 2029, maintaining that level through 2035. These transfers represent wages moving from Level I positions to higher-wage categories, creating substantial economic redistribution effects.

How the New Weighted Selection Process Would Work

Under the proposed rule, each H-1B registration would be weighted according to the job’s wage level before the lottery is conducted. In practical terms, employers registering for the H-1B cap would need to report the prevailing wage “level” that corresponds to their offered salary for the position. The prevailing wage levels are defined by the Department of Labor’s Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS) system, which categorizes wages into four tiers (Level I through IV) for each occupation and location based on required experience, education, and responsibility. For context:

- Wage Level I – Entry-level positions (around the 17th percentile of wages for the occupation in that area).

- Wage Level II – Qualified workers (34th percentile).

- Wage Level III – Experienced workers (50th percentile, roughly the median).

- Wage Level IV – Fully competent, expert workers (67th percentile or above).

The lottery weighting system would operate as follows:

- Level IV (highest wage): The registration is entered into the selection pool four times.

- Level III: Entered three times in the pool.

- Level II: Entered two times.

- Level I (lowest wage): Entered once in the pool.

| Wage Level | Percentile | Selection Weight | Average Salary (2024) | Selection Pool Entries |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level I (Entry) | 17th | 1x | $89,253 | 1 entry per registration |

| Level II (Qualified) | 34th | 2x | $115,742 | 2 entries per registration |

| Level III (Experienced) | 50th | 3x | $139,630 | 3 entries per registration |

| Level IV (Fully Competent) | 67th | 4x | $163,257 | 4 entries per registration |

In effect, a candidate whose job offer is at Level IV has four times the chance of selection as an otherwise identical candidate at Level I, since their name is replicated fourfold in the drawing. Level III gets a triple chance, and Level II double, relative to Level I. This weighting applies “when random selection is required because USCIS receives more registrations than needed to meet the cap” – which is virtually every year given excess demand.

Crucially, each individual (beneficiary) will only count once toward the cap regardless of multiple registrations. If a foreign worker is registered by several employers, they will still be treated as a single “unique beneficiary” in the lottery. That beneficiary would be assigned the highest weighting category among their registrations – but only one entry per weight slot for that person is considered. (For instance, if two different companies register the same person with one offering a Level I wage and another a Level III wage, USCIS would assign the beneficiary to Level I for lottery purposes to prevent gaming, as explained below, giving them just one Level I entry rather than one at each level.) This beneficiary-centric approach, recently adopted by USCIS, ensures that no one person can have an unfair advantage by sheer number of registrations; only the wage level will differentiate their selection odds.

After the weighted lottery is conducted, USCIS will select enough registrations to meet the 85,000 annual quota (factoring in expected petition approval rates). Employers whose registrations are selected will be notified and may then proceed to file full H-1B petitions for those beneficiaries.

Registration and Petition Process Under the New Rule

If the rule is finalized, the H-1B cap registration process (which takes place each year, typically in March) will include some new required information and stricter compliance measures:

- Including Wage Level on Registration: Employers (petitioners) must indicate the highest OEWS wage level that their offered salary meets or exceeds for the job’s occupation and location. This effectively means picking Level I, II, III, or IV on the registration form based on the wage the company commits to pay the H-1B worker. The registration will also require the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) code for the job and the location(s) of employment, since those determine the prevailing wage.

- Multiple Worksites or Positions: If the job involves multiple worksites or varying positions (for example, consulting work at different client locations, or an agent submitting for multiple end clients), the employer is required to use the lowest applicable wage level among all those locations/positions when registering. This rule is designed to prevent “gaming” the system by cherry-picking a briefly higher-paying location or role just to claim a higher wage level for the lottery. For instance, a company can’t list a Silicon Valley salary (Level IV) if the worker will mostly work in a lower-wage region at Level II – using the higher wage only 5% of the time – simply to boost lottery odds. The registration should reflect the lowest wage level that truly covers the job across all sites, ensuring the weighted lottery remains fair.

- Selection and Petition Filing: After the weighted selection, employers with selected registrations can file an H-1B cap-subject petition on behalf of the beneficiary (generally starting in April). Under the proposed rule, the petition must carry over and be supported by the same key details provided in the registration. This includes the same SOC occupation code, same wage level, and consistent offered wage that was indicated in the registration and on the Labor Condition Application (LCA) filed with the Department of Labor. In fact, the petition’s proffered wage must “equal or exceed the prevailing wage for the corresponding OEWS wage level in the registration” for that job and location. In short, an employer cannot win the lottery by claiming a high wage and then file the petition at a lower wage or different job – the terms on the petition have to match what was promised at registration.

- Evidence and Verification: USCIS will require petitioners to submit evidence justifying the selected wage level as of the date of registration. This could be, for example, a printout from the official DOL wage database showing the prevailing wage for the stated occupation, location, and level. If an employer used an alternative wage source (such as an independent survey or a collectively bargained wage) that yielded a wage below Level I, they still must select “Level I” on the registration (since Level I is the floor). The key is that USCIS will cross-check the wage level indicated at registration against the petition and its supporting LCA to “ensure [the employer] adheres to the wage level it indicated”. Any significant discrepancy or attempt to downgrade the position at filing time could raise a red flag.

- Integrity Measures: The proposal explicitly states that if any information in the registration or petition is found to be fraudulent or materially misrepresented, the petition will be denied or revoked. Each registrant must certify that the registration represents a “bona fide job offer” for the named beneficiary. By revising the regulations to emphasize this, DHS aims to deter shell registrations or placeholders with no real job behind them. Furthermore, USCIS may deny any new or amended petition by the same employer (or an affiliated entity) for that beneficiary if it appears the employer tried to “game” the system – for example, by first securing selection with a high wage, then filing a later petition at a much lower wage level. Such tactics would be deemed an attempt to “unfairly increase the odds of selection” without a genuine intent to employ the worker at the promised terms. In short, DHS is building in safeguards to ensure the weighted lottery rewards honest employers who will follow through on offering high-skilled jobs at commensurate pay, rather than those who might otherwise try to exploit the system.

It’s worth noting that if USCIS ever suspends the electronic registration requirement in a given year (due to technical issues or other reasons), the rule provides for a similar weighted process to apply directly to petitions. In that scenario, employers would file full petitions for all candidates, but USCIS would then select among those petitions with weighting by wage level (using the wage info supplied on the petition). The overall principle remains the same: whether at registration or petition stage, higher wage offers boost the chances of selection.

| Wage Level | Small Entity Petitions | Non-Small Entity Petitions | Percentage Small Entities | Selection Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level I | 16904 | 10734 | 61% | 1x |

| Level II | 18056 | 20075 | 47% | 2x |

| Level III | 2279 | 6814 | 25% | 3x |

| Level IV | 1136 | 2762 | 29% | 4x |

Legal Authority and Alignment with Congressional Intent

DHS asserts it has clear legal authority under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) and related laws to modify the H-1B selection process by regulation. In the proposed rule’s preamble, the agency cites INA §103(a) (8 U.S.C. §1103(a)), which gives the Homeland Security Secretary broad power to administer and enforce immigration laws and to establish regulations to carry out that authority. Additionally, INA §214(a)(1) authorizes the Secretary to set the “time and conditions” of nonimmigrant admissions by regulation, and INA §214(c)(1) empowers the Secretary to determine “how an importing employer may petition” for H-1B workers and what information to require. In essence, Congress left it to the executive agency to fill in procedural details of the H-1B cap selection, especially in situations (like simultaneous filings) not explicitly addressed in the statute. Federal courts have upheld USCIS’s discretion in this area – for example, supporting the use of random selection as a reasonable stopgap to handle oversubscription in the absence of specific statutory direction. The new weighted lottery is presented as another exercise of this discretion, grounded in “reasoned decision making” to better achieve the H-1B program’s objectives.

Importantly, DHS argues that the weighted selection advances the overarching purpose of the H-1B visa category as intended by Congress. The INA defines H-1B specialty occupations as those requiring specialized knowledge and a bachelor’s degree or higher, indicating that the visa is meant for highly skilled workers. Legislative history from the Immigration Act of 1990 (which established the modern H-1B program) shows that Congress sought to use H-1B visas to “meet U.S. employers’ need for highly skilled, specially trained personnel” in an increasingly sophisticated, competitive global economy. At the same time, Congress imposed the numerical cap and prevailing wage requirements to protect U.S. workers from wage depression and ensure H-1B hires are truly filling skill gaps, not displacing local labor. DHS contends that prioritizing higher wage (and thus presumably higher skill) H-1B candidates aligns with this dual intent – it helps employers get the talent they vitally need, while also favoring those foreign workers who are paid at levels that indicate they are among the most skilled (and are less likely to undermine prevailing wages). In support, the rule quotes policy commentators and legislators who described the H-1B program as intended to attract “the best and the brightest” and drive economic benefits.

The rule’s legal foundation is further buttressed by the Homeland Security Act (HSA), which transferred immigration services to DHS. HSA §102 and §402 charge the Secretary with setting immigration policies and administering visa programs in a way that protects the nation’s economic interests. DHS interprets this as a mandate to ensure the H-1B program is managed so that it bolsters (and does not diminish) U.S. economic competitiveness. By allocating visas to the highest skilled and paid workers, DHS believes it is upholding that mission. The agency is careful to note that nothing in the INA explicitly requires a pure lottery; rather, Congress implicitly allowed DHS to devise a fair method for selection when the cap is oversubscribed. Having already implemented electronic registration and other modernizations under that authority, DHS views the weighted selection as a logical next step, firmly within its regulatory powers and consistent with Congressional objectives for the H-1B program.

Comparison with the Current and 2021 Selection Systems

Current H-1B Lottery System (Random Selection)

Under the current system, USCIS uses a random lottery to select registrations when H-1B demand exceeds supply. Each Spring, employers submit electronic registrations for each prospective H-1B employee during a designated period. If the number of registrations exceeds the quota (as it always does in recent years), every registered beneficiary has an equal chance in the lottery, regardless of their salary or skill level. This means a software engineer job at a $150,000 salary and another at $70,000 are treated identically in terms of selection probability, as long as they meet the basic eligibility. In 2023, USCIS adjusted the process to a beneficiary-centric model – ensuring that if a candidate has multiple registrations, they only get one entry in the lottery – to curb abuse. But fundamentally, no qualitative factors are considered today. As the DHS proposal acknowledges, the random lottery is a “reasonable” way to distribute visas when oversubscribed, but “neither the optimal, nor the exclusive method” available. The randomness fails to differentiate between candidates and thus doesn’t target the visas to the highest skilled workers. In the current system, historically about one in four to one in three registrations is selected (e.g. around 25–30% selection rate in recent lotteries, depending on the number of entries).

By contrast, the proposed weighted system preserves the random draw but adds a merit-based weighting. For example, DHS estimates that if the weighted lottery were applied, an entry at Level IV might have roughly a 61% chance of selection, whereas a Level I entry might have only about a 15% chance, assuming similar registration volumes and wage distributions as recent years. (Under the current random lottery, both would simply have the same ~29% chance in that scenario.) This dramatic shift illustrates how the weighting steers the outcome: more visas would go to the higher wage brackets. DHS projects that under the new system, far fewer Level I petitions would be selected (roughly 10,000 fewer annually), while hundreds0 more Level III and Level IV petitions would win visas, filling the cap with a more skilled cohort. Still, Level I and II candidates are not eliminated – many thousands could still be selected – but they would form a smaller share of the total pool than they do under the random lottery.

The 2021 “Wage Priority” Rule and How This Differs

It’s important to distinguish the new proposal from a previous attempt to change the H-1B selection process in late 2020/early 2021. In January 2021, in the final weeks of the Trump Administration, DHS published a rule titled “Modification of Registration Requirement for Petitioners Seeking to File Cap-Subject H-1B Petitions“. That rule – often referred to as the 2021 H-1B wage prioritization rule – would have completely replaced the lottery with a rank-order selection based on wage levels. USCIS planned to “first select registrations with offered wages meeting Level IV, then Level III, and so on, in descending order” until the cap was filled. Only if there were more registrations within the same wage level than remaining slots would a lottery be used for that level. In practice, this meant Level IV petitions would consume the cap first; DHS acknowledged at the time that under that scheme, Level I cases would likely never be selected, and even Level II would have low odds. The 2021 rule was met with controversy and a lawsuit. It was **delayed by the incoming Biden Administration and ultimately vacated by a federal court in September 2021 on procedural grounds (the court found it was improperly issued, without even reaching substantive challenges). DHS officially withdrew the rule before it ever took effect.

The new 2025 proposed rule differs significantly from the 2021 approach. DHS now believes the previous rank-and-select method was “not [the] optimal approach” because it “effectively left little or no opportunity” for any lower-wage or entry-level workers, some of whom could still be highly skilled in their fields. In the preamble, DHS notes that an entry-level professional in a very advanced occupation could be quite skilled (for example, a fresh Ph.D. in a cutting-edge research role might be paid at Level I if it’s their first job, yet they are hardly “low skill”). The weighted lottery is presented as a more balanced solution: instead of strictly ranking by wage and potentially excluding entire categories, it assigns weights so that higher wage offers greatly increase selection chances without guaranteeing them. Lower-level candidates still have a fighting chance in the lottery, even if diminished. DHS explicitly states it sought to avoid “effectively precluding those at lower wage levels” while still tilting toward the highest paid. In short, the 2021 rule was an “all-or-nothing” wage priority system, whereas the 2025 proposal is a hybrid weighted lottery – a middle path intended to satisfy the same goal of elevating skill level, but with more flexibility and fairness across the wage spectrum.

Procedurally, the new rule is going through the standard Notice-and-Comment process properly (unlike the rushed 2021 rule), which should help it avoid the legal pitfalls that doomed the prior attempt. It is currently a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM), open for public comment for at least 30 days after publication. DHS will review feedback, possibly revise the rule, and then publish a final rule, which would likely take effect for the next H-1B cap season after finalization. Stakeholders remember the 2021 experience and are weighing in to ensure the final approach balances industry needs and program integrity.

Implications for Employers and Applicants

If this weighted selection rule comes into force, it will bring both opportunities and challenges for H-1B employers and foreign professionals:

- Higher Odds for Higher Wages: Companies that can afford to pay (or are already paying) top-of-market salaries for their H-1B candidates will have a much better chance of securing a visa. For example, an employer offering a Level IV wage (67th percentile+) could see the candidate’s selection probability roughly double compared to the current lottery. Even Level III wages (around the median) could see a substantial boost in odds (up ~50% higher than the status quo). This creates a strong incentive for employers, especially in tech and other high-paying industries, to budget for higher salaries for foreign hires. It may also encourage them to focus cap-subject filings on more senior or specialized positions that justify higher pay, as those are more likely to win a visa under the new system.

- Lower Odds (But Not Zero) for Entry-Level Positions: Employers who traditionally hire H-1B workers at entry-level or junior positions (common for new graduates, for instance) will face reduced odds of success. A Level I petition might have only around a 15% chance in the lottery instead of ~30% previously, assuming similar demand levels. This doesn’t bar lower-wage jobs from the H-1B program, but it means companies might need to submit more registrations to achieve the same chance of selection as before, or consider raising the wage offer if possible to move into Level II. Some smaller businesses, nonprofits, or firms in lower-paying regions could feel disadvantaged. However, DHS’s design still grants thousands of visas to Level I and II workers each year, so capable candidates at all levels can still hope for selection – it is weighted, not winnowed to one group. Employers at the lower end of the wage scale will simply need to be mindful that the lottery will no longer be an even playing field, and adjust their H-1B application strategies accordingly (e.g., focusing on truly critical hires, potentially improving compensation packages, or exploring cap-exempt H-1B avenues where possible).

- Impact on Workforce Planning: The overall talent pool of H-1B visa holders is likely to shift toward higher salary roles, which could mean more experienced professionals coming in through the program. For industries, this might alleviate some concerns that H-1Bs were being used to fill cheaper labor slots. U.S. workers might benefit from the upward wage pressure – if employers raise wages for foreign hires to compete in the lottery, they may also need to offer better pay to domestic hires in similar roles to maintain parity. On the flip side, certain fields that traditionally rely on H-1Bs with moderate wages (for example, some teaching positions, entry-level research associates, etc.) might find it harder to get visas, potentially exacerbating shortages in those areas unless wages increase. DHS’s view is that the change will “benefit the economy” by directing visas to those who can contribute at the highest levels and salary ranges, thereby fueling innovation and not just filling routine jobs.

- Need for Compliance and Honesty: Employers will have to carefully evaluate and document the appropriate wage level before entering the lottery. This means working closely with immigration counsel or HR to determine the correct prevailing wage for the job’s requirements and ensuring the offered salary meets that level. The days of putting in a registration with minimal info and worrying about the specifics later are over – under this rule, the registration locks in a commitment. If selected, the petition must match what was promised (job role, location, wage level). Any attempt to misrepresent a wage or job to gain selection is likely to result in denial or revocation. Employers should also be aware that USCIS will scrutinize any post-selection changes (like suddenly trying to relocate the job to a cheaper city or cutting the salary) and can reject such moves as bad-faith gaming. In short, integrity will be heavily enforced – the gamble of “offer high for the lottery, then adjust down later” will not work. This means employers must secure internal approval for the salary and position up front, as they will be locked into those terms if they win a visa slot.

- Mitigation for Smaller Employers and Others: While big tech firms and others who pay top dollar may celebrate this change, smaller companies or startups should note there are still options and silver linings. First, because lower-level petitions aren’t barred, a compelling entry-level candidate can still get through – especially if overall registration numbers ever dip, the lottery might not even be needed for some levels. Second, employers might improve their odds by offering slightly higher wages than they otherwise would – even moving a position from just below Level II to just above Level II could double its chances by bumping it to the next tier. DHS’s analysis even acknowledges that the rule could induce some wage increases for H-1B hires, and it views that positively. Additionally, cap-exempt avenues (such as hiring through universities or nonprofit research institutions, which aren’t subject to the lottery) remain unchanged. Companies can also explore alternative visas or programs for international talent who might not win in the H-1B weighted lottery (for example, the O-1 visa for individuals of extraordinary ability, or the STEM OPT extension for U.S.-educated grads as a bridge to another H-1B season).

- Transparency and Fairness: For the foreign applicants (prospective H-1B beneficiaries) themselves, the process will become more transparent in terms of understanding their odds. Under the lottery, many felt it was pure luck; under the weighted system, candidates will know that their qualifications reflected in salary offer do play a role. This could encourage candidates to negotiate for higher starting salaries with employers (since it not only benefits them financially but could secure their visa). However, it might also lead to disappointment for those in lower-paid sectors. Overall, the hope is that by realigning the selection with skill and wage, the H-1B visa’s reputation as a tool for innovation and high-skilled talent is reinforced, and public confidence in the program’s fairness improves.

Conclusion

The DHS’s proposed weighted selection rule represents a significant policy shift for the H-1B visa program. By moving away from a purely random lottery to a system that prioritizes higher-wage, higher-skill petitions, the agency aims to better fulfill the H-1B program’s mission of bringing in top talent to boost the U.S. economy. The change is motivated by years of sky-high demand, concerns that the lottery doesn’t target the “best and brightest,” and incidents of gaming the system. The new process would give employers who offer premium salaries a competitive edge in the annual H-1B draw, while still keeping the door open – if narrower – for positions at all wage levels.

From a legal and policy standpoint, DHS is on solid footing in asserting authority to make this change, grounding it in the INA’s broad delegation of rulemaking power and in Congressional intent to use H-1B visas for skilled labor shortages. The proposal consciously learns from the failed 2021 wage-priority rule by adopting a more balanced, weighted approach that avoids all-or-nothing outcomes.

For employers and foreign professionals, the rule (if finalized) will necessitate adaptation. Companies will need to strategize and possibly increase wage offers to remain competitive in the H-1B race, and ensure absolute honesty and consistency in the process. High-paying jobs stand to benefit, whereas lower-paying H-1B roles face tougher odds but not total exclusion. Over time, this could elevate the profile of H-1B workers as a group, potentially raising average salaries and skill levels among visa holders.

As of now, the rule is in proposal stage (with comments from the public invited), and no changes will affect the upcoming H-1B season until a final rule is formally adopted. Still, businesses and prospective H-1B applicants should begin preparing for a likely future where merit (as measured by wage) plays a defining role in H-1B visa allocation. The H-1B lottery, it seems, is evolving from a game of chance to a more weighted contest – one intended to ensure that America’s limited visas go to those foreign workers who are the most skilled, most in-demand, and most highly valued by their employers.