The evolution of American immigration policy across 46 presidencies reveals a complex tapestry of attitudes, policies, and societal pressures that have shaped the nation’s approach to welcoming newcomers. This comprehensive analysis examines each president’s stance on immigration, revealing distinct patterns across different historical eras and highlighting the profound shifts in American immigration philosophy from the nation’s founding to the present day.

Historical Overview: Five Distinct Eras of Presidential Immigration Policy

American presidential approaches to immigration can be categorized into five distinct historical periods, each characterized by prevailing social, economic, and political conditions that influenced policy decisions.

The Early Republic Era (1789-1860): The Open Door Tradition

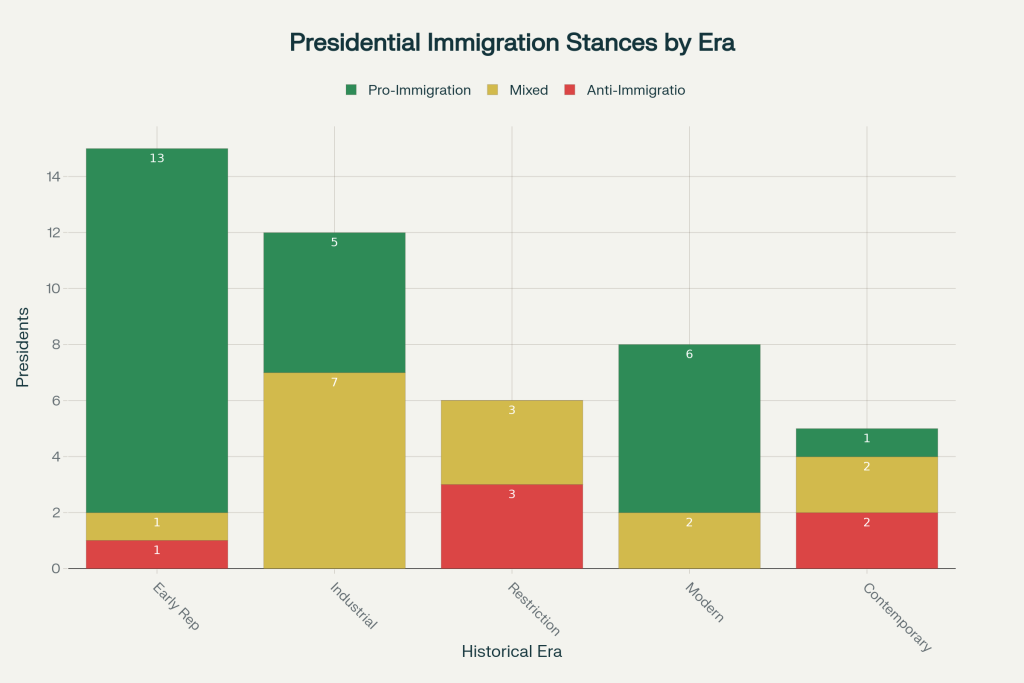

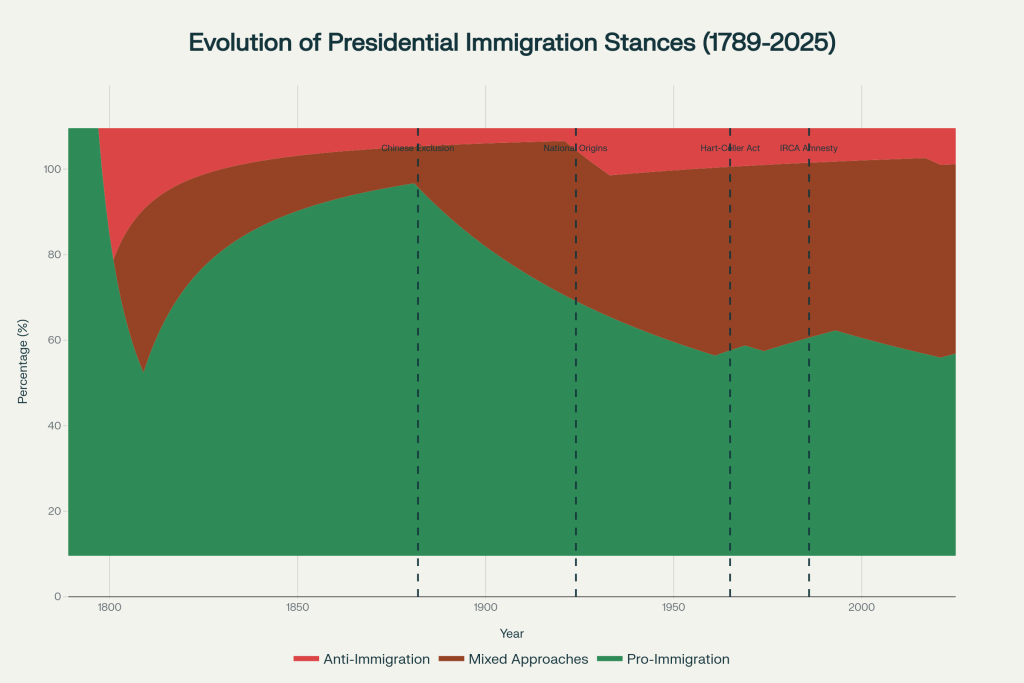

The founding era of American immigration policy was overwhelmingly welcoming, with 13 out of 15 presidents adopting pro-immigration stances. This period established the fundamental American tradition of viewing immigration as essential for nation-building and economic development. The Founding Fathers understood that populating the vast American territories required active encouragement of immigration, leading to policies that facilitated naturalization and westward expansion.

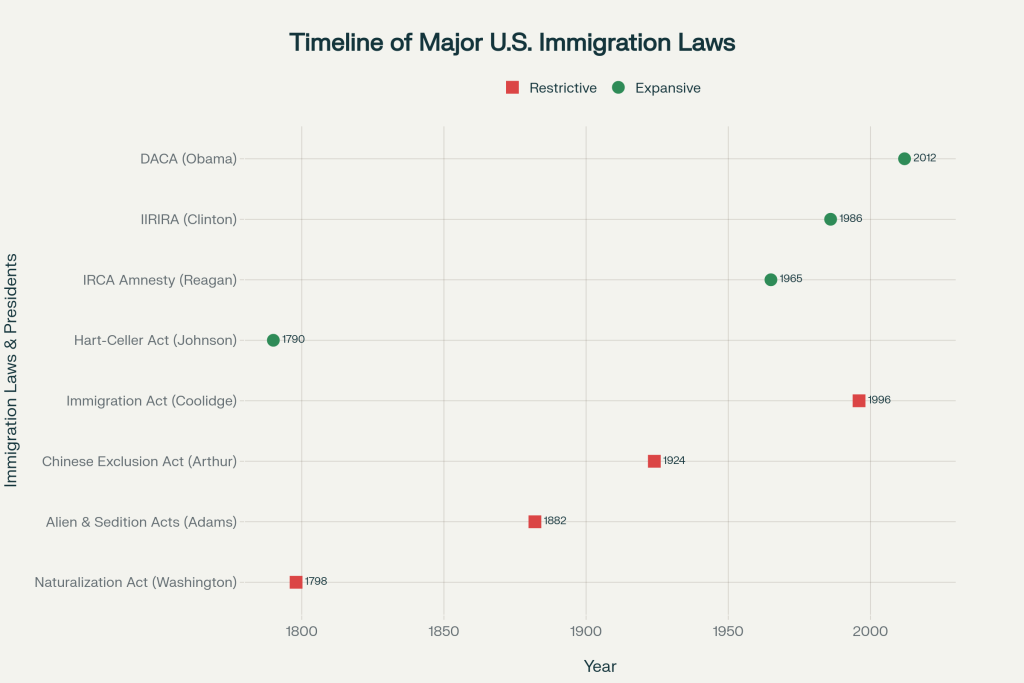

George Washington, America’s first president, established the precedent with the Naturalization Act of 1790, requiring only two years of residency for citizenship. This welcoming approach continued through most presidencies of this era, with presidents like Thomas Jefferson advocating for immigration while simultaneously expressing concerns about rapid cultural assimilation. The period saw the development of the fundamental American concept of the nation as a “land of opportunity” for those seeking better lives.

The Industrial Era (1861-1920): Immigration Becomes Contested

The Industrial Era marked a turning point in American immigration policy, characterized by the first significant restrictions and the emergence of nativist sentiments. This period witnessed 5 pro-immigration presidents but also 6 with mixed or restrictive approaches, reflecting growing tensions between economic needs and cultural anxieties.

Abraham Lincoln’s presidency during the Civil War demonstrated the continued pro-immigration tradition, with the Contract Labor Act of 1864 actively recruiting foreign workers for industrial development. However, the era’s end brought significant restrictions, beginning with Chester A. Arthur’s reluctant signing of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, marking America’s first race-based immigration law. Grover Cleveland’s mixed approach, including his veto of literacy tests while supporting Chinese exclusions, exemplified the era’s contradictory impulses.

Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency embodied the era’s “progressive” approach to immigration, promoting “True Americanism” while supporting restrictions on Asian immigration. His policies balanced humanitarian concerns with eugenic theories popular at the time, establishing inspection procedures at Ellis Island while maintaining discriminatory practices against certain nationalities.

The Restrictionist Era (1921-1960): The Great Closing

The Restrictionist Era represents the most dramatic departure from America’s traditional immigration policies. No president during this period adopted purely pro-immigration stances, with 3 explicitly anti-immigration presidents and others maintaining mixed approaches shaped by wartime and post-war circumstances.

Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge presided over the establishment of the most restrictive immigration system in American history. The Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924 created the national origins quota system, designed to preserve America’s ethnic composition as it existed in 1890. These laws reduced annual immigration from over 800,000 to approximately 150,000, with 82% of available visas allocated to Western and Northern European countries.

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s wartime presidency exemplified the era’s contradictions, implementing the Japanese American internment through Executive Order 9066 while simultaneously providing refuge for European displaced persons. Harry S. Truman’s post-war approach showed the beginning of change, as he vetoed the discriminatory McCarran-Walter Act of 1952 while supporting displaced persons programs.

Dwight D. Eisenhower’s presidency maintained restrictionist policies while dramatically enforcing them through “Operation Wetback” in 1954, demonstrating how enforcement could be intensified even within existing restrictive frameworks.

The Modern Era (1961-2000): The Great Reopening

The Modern Era witnessed a revolutionary transformation in American immigration policy, beginning with John F. Kennedy’s advocacy for reform and culminating in the Hart-Celler Act of 1965. This period saw 6 pro-immigration presidents and only 1 with mixed restrictive approaches, marking the most consistent pro-immigration period since the Early Republic.

Kennedy’s advocacy laid the groundwork for reform, arguing that the national origins system violated fundamental American principles. Lyndon B. Johnson’s signing of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 at the Statue of Liberty symbolically reopened America’s doors, abolishing discriminatory quotas and establishing the family-based immigration system that remains today. The act’s unintended consequence was “chain migration,” as naturalized immigrants could sponsor relatives in an ever-expanding process.

Jimmy Carter’s presidency established the modern refugee system through the Refugee Act of 1980, creating standardized procedures for admitting those fleeing persecution. His humanitarian approach, particularly toward Southeast Asian refugees, demonstrated America’s renewed commitment to providing sanctuary for the oppressed.

Ronald Reagan’s presidency produced the most significant immigration reform since 1965 with the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, providing amnesty to nearly 3 million unauthorized immigrants while attempting to strengthen border security. Reagan’s approach embodied the conservative tradition of supporting immigration while emphasizing law and order.

The era concluded with George H.W. Bush’s Immigration Act of 1990, which expanded legal immigration pathways and created the diversity lottery system, reflecting continued commitment to immigration expansion.

The Contemporary Era (2001-Present): Security and Polarization

The Contemporary Era has been defined by the tension between security concerns and humanitarian traditions, producing the most polarized immigration politics in American history. The period includes 2 anti-immigration presidents, 1 pro-immigration president, and others with mixed approaches emphasizing either enforcement or security.

The September 11 attacks fundamentally altered immigration policy, with George W. Bush’s administration implementing extensive security measures while attempting comprehensive immigration reform. Bush’s mixed record included increased border security and the creation of the Department of Homeland Security while supporting paths to legalization for unauthorized immigrants.

Barack Obama’s presidency exemplified the era’s enforcement-focused approach, earning him the moniker “deporter-in-chief” despite implementing protective programs like DACA. Obama’s record deportation numbers reflected the tension between humanitarian goals and political realities.

Donald Trump’s first presidency marked the most restrictionist approach since the 1920s, implementing travel bans, family separation policies, and dramatic reductions in refugee admissions. His “America First” immigration policy explicitly rejected the post-1965 consensus on immigration.

Joe Biden’s presidency attempted to restore Obama-era policies while addressing unprecedented border challenges, demonstrating the ongoing difficulty of balancing humanitarian commitments with border security.

Trump’s return to office in 2025 has brought unprecedented enforcement measures, including national emergency declarations and mass deportation operations, representing the most aggressive restriction approach in modern American history.

Key Policy Turning Points and Presidential Leadership

Several presidential decisions fundamentally altered the trajectory of American immigration policy, demonstrating how individual leadership can reshape national approaches to immigration.

The Alien and Sedition Acts (1798): America’s First Immigration Restriction

John Adams’s presidency produced America’s first significant immigration restrictions through the Alien and Sedition Acts, extending naturalization requirements from 5 to 14 years and authorizing presidential deportation powers. These acts established the precedent for using immigration policy as a tool of national security and political control, though they were largely repealed under Jefferson.

The Chinese Exclusion Act (1882): America’s First Racial Immigration Law

Chester A. Arthur’s reluctant signing of the Chinese Exclusion Act marked America’s departure from its colorblind immigration tradition. Initially vetoing the twenty-year exclusion as too harsh, Arthur signed a modified ten-year version following intense political pressure. This law established the precedent for race-based immigration restrictions and remained in effect until 1943.

The National Origins Quota System (1921-1924): The Great Restriction

Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge’s implementation of the quota system represented the most dramatic restriction in American immigration history. The 1924 Immigration Act reduced annual immigration by over 80% and explicitly aimed to preserve America’s Anglo-Saxon character. This system remained in effect until 1965, fundamentally altering American demographics for four decades.

The Hart-Celler Act (1965): The Second Great Opening

Lyndon B. Johnson’s Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 abolished the discriminatory quota system and reopened America to global immigration. Signed at the Statue of Liberty, the act prioritized family reunification and skilled immigration, unintentionally creating the foundation for dramatic demographic change. The law’s emphasis on family reunification produced “chain migration” effects that continue to shape immigration patterns today.

Reagan’s Immigration Reform (1986): The Great Amnesty

Ronald Reagan’s Immigration Reform and Control Act provided the largest legalization in American history, granting legal status to nearly 3 million unauthorized immigrants. Reagan personally referred to the program as “amnesty,” arguing that bringing people “out of the shadows” served both humanitarian and practical purposes. The act’s failure to prevent future unauthorized immigration became a cautionary tale for subsequent reform efforts.

Contemporary Challenges and Presidential Responses

Modern presidents have grappled with unprecedented challenges in immigration policy, from security threats to humanitarian crises, requiring new approaches to traditional policy tools.

Post-9/11 Security Integration

The September 11 attacks fundamentally altered immigration policy by integrating security concerns into every aspect of the system. The creation of the Department of Homeland Security centralized immigration functions and prioritized security screening, establishing the framework that continues to shape policy today.

The DACA Innovation

Barack Obama’s creation of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals represented a novel use of executive authority to address Congressional inaction. DACA’s success in protecting nearly 800,000 young immigrants demonstrated how presidents could use prosecutorial discretion to implement humanitarian policies despite legislative gridlock.

Contemporary Enforcement Strategies

Recent presidents have developed increasingly sophisticated enforcement strategies, from Obama’s prioritized enforcement to Trump’s comprehensive restriction approach. These strategies reflect the evolution of immigration enforcement from a primarily border-focused activity to a comprehensive system affecting all aspects of immigration law.

Analyzing Presidential Immigration Stances: Patterns and Conclusions

The comprehensive analysis of 46 American presidencies reveals several important patterns in presidential approaches to immigration policy.

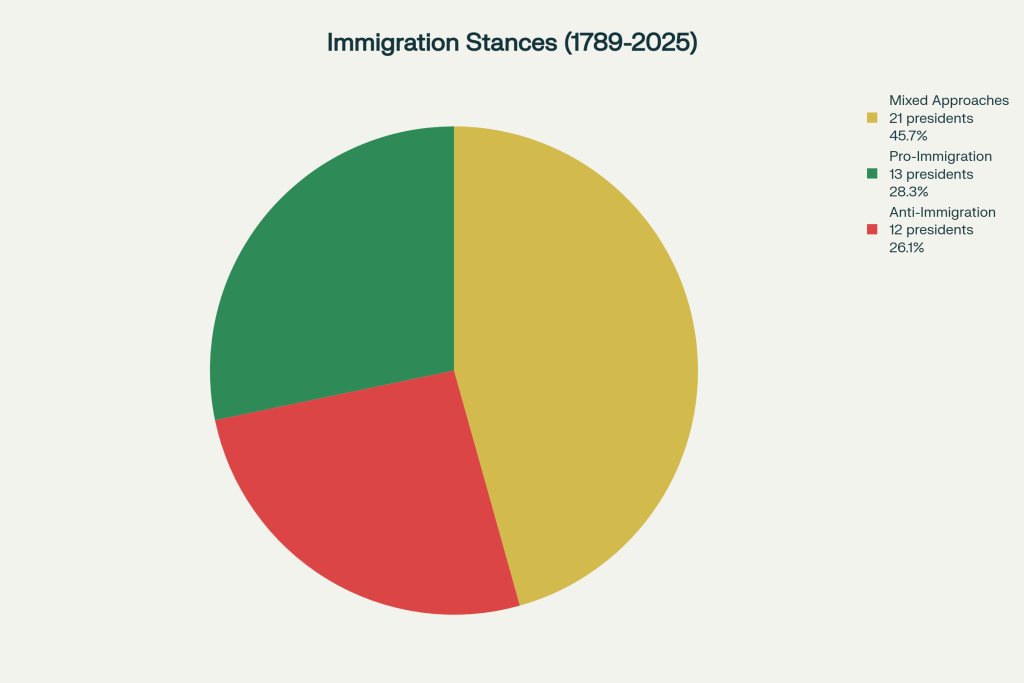

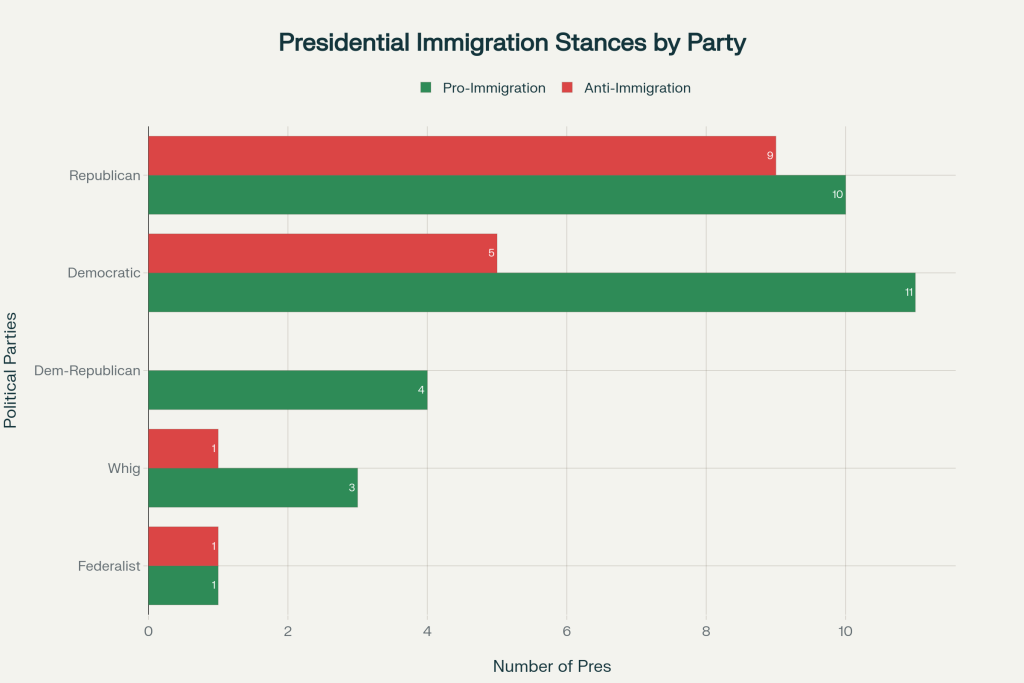

The Dominance of Pro-Immigration Sentiment

Despite contemporary perceptions of American restrictionism, 25 of 46 presidents (54%) adopted fundamentally pro-immigration stances throughout their presidencies. This includes strong majorities in the Early Republic (13 of 15) and Modern Era (6 of 8), suggesting that pro-immigration approaches have been more common than restrictionist ones throughout American history.

The Restrictionist Exception

Truly anti-immigration presidents have been relatively rare, with only 6 presidents (13%) adopting consistently restrictionist approaches. These presidencies clustered in specific periods: John Adams during the early partisan conflicts, Harding and Coolidge during the 1920s nativist period, Herbert Hoover during the Depression, and Donald Trump in the contemporary era.

The Mixed Approach Plurality

Fifteen presidents (33%) adopted mixed approaches, reflecting the complexity of immigration policy and the multiple pressures facing presidential decision-making. These mixed approaches often reflected evolving circumstances, such as wartime security needs or changing economic conditions.

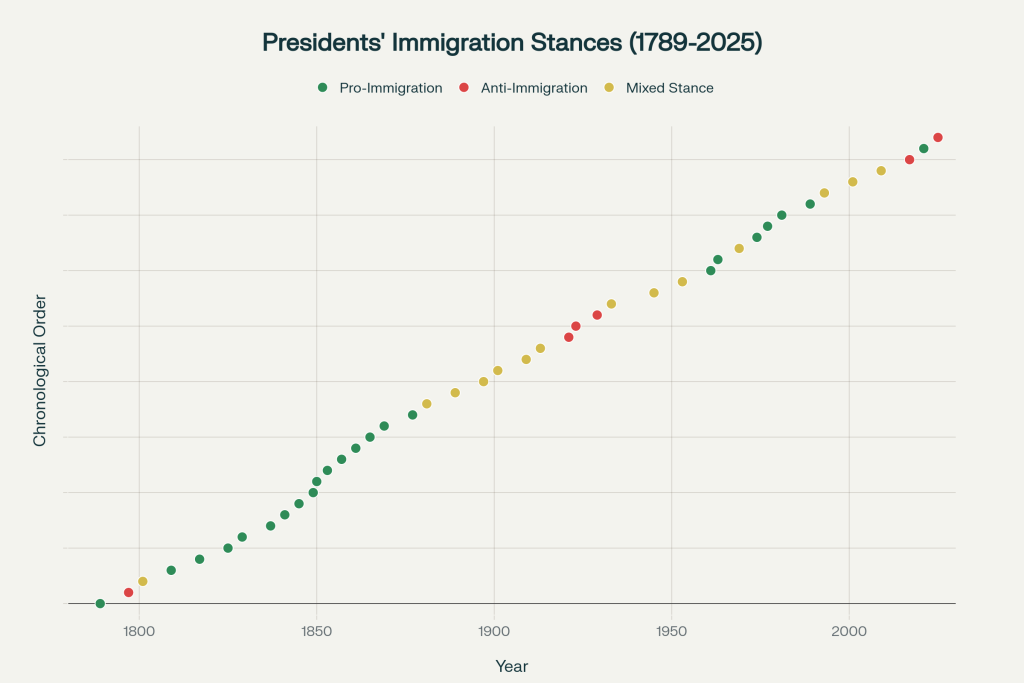

Era-Specific Patterns

Each historical era produced distinct patterns of presidential behavior. The Early Republic’s overwhelming pro-immigration consensus gave way to the Industrial Era’s growing restrictions, followed by the Restrictionist Era’s systematic exclusion, the Modern Era’s reopening, and the Contemporary Era’s security-focused polarization.

The Evolution of Presidential Power in Immigration

Presidential authority over immigration has expanded dramatically since the founding era, with modern presidents wielding extensive executive powers that would have been unimaginable to the Founders.

| President | Immigration_Stance | Key_Policies |

|---|---|---|

| George Washington (1789-1797) | Pro-Immigration | Naturalization Act of 1790 (2-year residency for citizenship) |

| John Adams (1797-1801) | Anti-Immigration | Alien and Sedition Acts (1798): Extended residency to 14 years, deportation powers |

| Thomas Jefferson (1801-1809) | Mixed/Cautious | Reduced naturalization back to 5 years (1802), expressed immigration concerns |

| James Madison (1809-1817) | Pro-Immigration | Continued 5-year naturalization policy, supported westward expansion |

| James Monroe (1817-1825) | Pro-Immigration | Monroe Doctrine era, welcomed European immigrants for expansion |

| John Quincy Adams (1825-1829) | Pro-Immigration | Supported infrastructure projects using immigrant labor |

| Andrew Jackson (1829-1837) | Pro-Immigration | Opposed nativism and Know-Nothing Party, supported democratic expansion |

| Martin Van Buren (1837-1841) | Pro-Immigration | Continued open immigration policies of Democratic Party |

| William Henry Harrison (1841) | Pro-Immigration | Brief presidency, maintained existing open-door policies |

| John Tyler (1841-1845) | Pro-Immigration | Maintained open immigration stance during territorial expansion |

| James K. Polk (1845-1849) | Pro-Immigration | Expansionist policies, Mexican-American War opened new territories |

| Zachary Taylor (1849-1850) | Pro-Immigration | Brief presidency, maintained status quo on immigration |

| Millard Fillmore (1850-1853) | Pro-Immigration | Open immigration during westward expansion and California Gold Rush |

| Franklin Pierce (1853-1857) | Pro-Immigration | Kansas-Nebraska Act supported by immigrant communities |

| James Buchanan (1857-1861) | Pro-Immigration | Maintained open policies despite slavery tensions |

| Abraham Lincoln (1861-1865) | Pro-Immigration | Contract Labor Act (1864), Homestead Act (1862) actively recruited immigrants |

| Andrew Johnson (1865-1869) | Pro-Immigration | Continued Lincoln’s pro-immigration policies during Reconstruction |

| Ulysses S. Grant (1869-1877) | Pro-Immigration | Post-Civil War immigration encouraged for industrial reconstruction |

| Rutherford B. Hayes (1877-1881) | Pro-Immigration | Open immigration during Gilded Age industrial expansion |

| James A. Garfield (1881) | Pro-Immigration | Brief presidency, no major immigration policy changes |

| Chester A. Arthur (1881-1885) | Mixed/Restrictive | Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) – first major racial immigration restriction |

| Grover Cleveland (1885-1889, 1893-1897) | Mixed/Restrictive | Vetoed literacy test (1896), signed Scott Act (1888) restricting Chinese |

| Benjamin Harrison (1889-1893) | Mixed/Restrictive | Immigration Act of 1891 – established federal control of immigration |

| William McKinley (1897-1901) | Mixed/Restrictive | Continued restrictive policies toward Chinese, Spanish-American War |

| Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909) | Mixed/Progressive | Progressive era “”True Americanism,”” supported European immigration, restricted Asian |

| William Howard Taft (1909-1913) | Mixed/Restrictive | Continued Roosevelt policies with more business-friendly approach |

| Woodrow Wilson (1913-1921) | Mixed/Restrictive | Vetoed Immigration Act (1917) over literacy tests, signed after override |

| Warren G. Harding (1921-1923) | Anti-Immigration | Emergency Quota Act (1921) – established national origins quotas |

| Calvin Coolidge (1923-1929) | Anti-Immigration | Immigration Act (1924) – severely restricted immigration with national origins system |

| Herbert Hoover (1929-1933) | Anti-Immigration | Maintained restrictive 1920s policies during Great Depression |

| Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933-1945) | Mixed/Wartime | Japanese internment (Executive Order 9066), European refugee acceptance |

| Harry S. Truman (1945-1953) | Mixed/Post-War | Vetoed McCarran-Walter Act (1952), supported displaced persons programs |

| Dwight D. Eisenhower (1953-1961) | Mixed/Security | Operation Wetback (1954), maintained quotas with strict enforcement |

| John F. Kennedy (1961-1963) | Pro-Immigration | Advocated immigration reform, opposed discriminatory national origins system |

| Lyndon B. Johnson (1963-1969) | Pro-Immigration | Hart-Celler Act (1965) – abolished quotas, established family-based system |

| Richard Nixon (1969-1974) | Mixed/Restrictive | Maintained Johnson policies, focused on Vietnam War refugees |

| Gerald Ford (1974-1977) | Pro-Immigration | Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act (1975) |

| Jimmy Carter (1977-1981) | Pro-Immigration | Refugee Act (1980), welcomed Southeast Asian refugees, modern refugee system |

| Ronald Reagan (1981-1989) | Pro-Immigration | Immigration Reform and Control Act (1986) – amnesty for 3 million |

| George H.W. Bush (1989-1993) | Pro-Immigration | Immigration Act (1990) – expanded legal immigration, diversity lottery |

| Bill Clinton (1993-2001) | Mixed/Enforcement | IIRIRA (1996), welfare reform affecting immigrants, Operation Gatekeeper |

| George W. Bush (2001-2009) | Mixed/Security | Post-9/11 security measures, attempted comprehensive reform, DREAM Act |

| Barack Obama (2009-2017) | Mixed/Enforcement | DACA (2012), DAPA attempt, record deportations, enforcement priorities |

| Donald Trump (2017-2021) | Anti-Immigration | Travel ban, border wall, family separations, reduced refugee admissions |

| Joe Biden (2021-2025) | Pro-Immigration | Reversed Trump policies, increased refugee admissions, DACA restoration |

| Donald Trump (2025-Present) | Anti-Immigration | National emergency, mass deportation operations, border militarization |

Early Constitutional Limits

The Constitution granted Congress authority over naturalization but said nothing about immigration control, leading to the early emphasis on state and local regulation. Early presidents had limited direct authority over immigration beyond implementing Congressional legislation.

The Growth of Executive Authority

The twentieth century witnessed dramatic expansion of presidential immigration authority, from Roosevelt’s wartime powers to modern presidents’ use of executive orders, prosecutorial discretion, and national security authorities. This expansion reflects both Congressional delegation and presidential assertion of inherent executive powers.

Contemporary Executive Actions

Recent presidents have increasingly used executive authority to implement immigration policies in the absence of Congressional action, from Obama’s DACA to Trump’s travel bans to Biden’s border policies. This trend reflects both the polarization of immigration politics and the practical need for executive flexibility in addressing evolving challenges.

The historical analysis of presidential immigration stances reveals that American immigration policy has been shaped more by pro-immigration leaders than by restrictionists, despite periodic waves of restriction. The current polarized environment represents a departure from the historical norm of broad presidential support for immigration, suggesting that contemporary debates over immigration reflect deeper changes in American political culture rather than consistent historical patterns.

The data demonstrates that presidential leadership has been crucial in shaping immigration policy, with individual presidents capable of fundamentally altering the direction of American immigration law through their policy choices and moral leadership. From Washington’s welcoming naturalization policies to Johnson’s revolutionary Hart-Celler Act to Reagan’s comprehensive amnesty, presidential decisions have repeatedly reshaped American immigration policy and, by extension, American society itself.

This comprehensive examination of 46 presidencies provides essential historical context for contemporary immigration debates, demonstrating that the American tradition has generally favored welcoming newcomers while adapting to changing circumstances and security needs. The challenge for future presidents will be balancing this historic commitment to immigration with the practical demands of modern governance, security concerns, and evolving public opinion in an increasingly interconnected world.