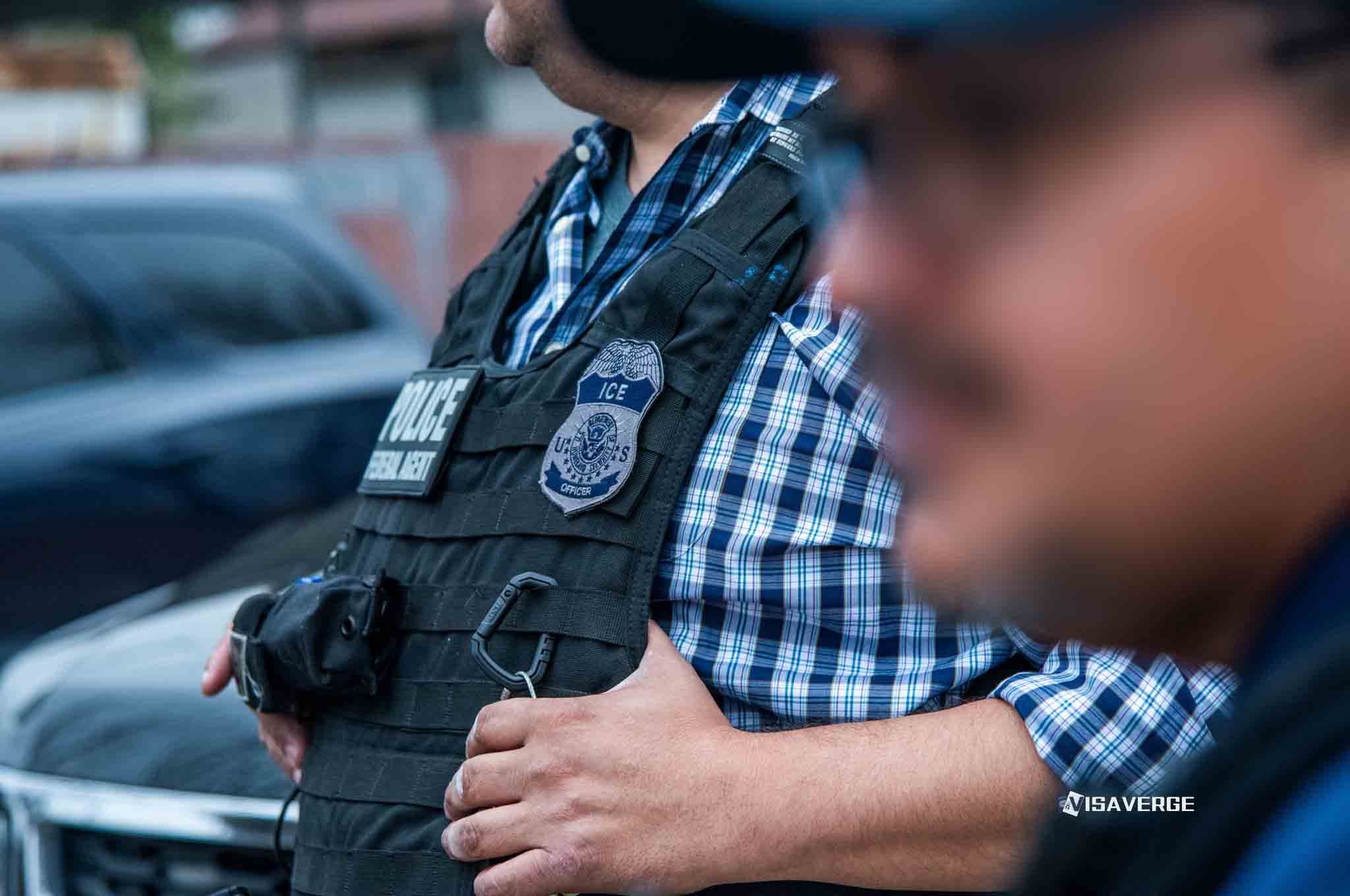

(CANADA) A new push to narrow who can claim refugee protection in Canada is reshaping options for people who may qualify for asylum in Canada but remain held in ICE detention in the United States 🇺🇸. The most immediate change to watch is Bill C-2, tabled in June 2025, which would make many late asylum filings ineligible and tighten rules for people who crossed the land border from the United States 🇺🇸. At the same time, Canada’s 2025 plan cuts the humanitarian stream to 20,000 places—a 31% drop—while keeping overall immigration targets high. That mix of tougher rules and fewer spaces, paired with heavy backlogs at the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB) of Canada, adds real pressure for detainees hoping to move north after release.

Key Changes Reshaping Asylum Options in 2024–2025

Canada still preserves the core right to seek protection at an official port of entry or within the country, but the policy environment around asylum is tightening.

In 2023, Canada received roughly 140,000 asylum claims—more than double the previous year. Cases surged faster than hearings could be set, and the IRB, which decides refugee claims, has struggled to keep pace despite short-term funding increases. These delays now influence life planning and legal strategy for many claimants.

The federal Immigration Levels Plan 2024–2026 sets a target of about 500,000 permanent resident admissions per year by 2025, with a strong focus on economic categories. However, the humanitarian and refugee stream is reduced sharply in 2025, from 29,000 to 20,000. That shift means fewer resettlement and protected-person pathways and places more weight on the claim process at ports of entry and inland offices.

Bill C-2 proposes two broad limits that would change eligibility for many people:

– Anyone who entered Canada after June 24, 2020 and filed an asylum claim more than one year after entry would be ineligible.

– Anyone who crossed the Canada–U.S. border irregularly and filed a claim after 14 days would be ineligible.

The bill also gives wider executive powers to cancel or suspend immigration documents. If enacted as introduced, it would push people to file quickly and almost entirely at official ports of entry rather than between them. The combined effect of those time bars and fewer humanitarian spaces would make late filings far riskier.

What This Means for People in ICE Detention

For those in ICE detention who may qualify for asylum in Canada, three main barriers stand in the way: physical, legal, and capacity.

Physical barrier

– There is no direct program to transfer detainees from ICE detention in the U.S. into Canada’s asylum system.

– Release decisions rest with U.S. authorities; detainees often face long and uncertain timelines.

– Analysis by VisaVerge.com finds no Canadian administrative channel that moves detainees straight from ICE custody into the Canadian asylum process.

Legal barrier

– The Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA) generally requires people to seek protection in the first safe country they reach (typically the U.S.), which usually blocks land-border claims from the United States into Canada.

– Exceptions exist (family reunification, unaccompanied minors, etc.), and legal challenges have affected how those exceptions are read, but the STCA still limits who can file at land ports.

– Timing is critical. Under Bill C-2, an irregular entry followed by a claim filed after 14 days would be ineligible. For someone released from ICE custody, that 14‑day clock could be decisive.

Capacity barrier

– The IRB’s heavy caseload and reduced humanitarian targets create longer wait times and less predictable outcomes.

– People who expect quick resolution after release from ICE detention may be surprised by how slowly decisions come, even once a claim is accepted for a hearing.

Entry Routes, Timing Risks, and Filing Windows

The path for a person leaving ICE detention who hopes to seek asylum in Canada narrows to several steps, each with its own legal and practical risk.

Official port of entry filing

– Filing at a border crossing is the cleanest legal route.

– The STCA applies at land ports, so a person typically needs to fit an exception to make a claim.

– If an exception applies, officers forward the claim to the IRB for a future hearing.

Irregular entry from the U.S. into Canada

– This route has been common historically, but Bill C-2 targets it with a 14‑day filing window.

– Crossing irregularly and waiting past 14 days to apply would be ineligible if the bill becomes law.

– Even now, irregular entry triggers credibility concerns and potential detention in Canada.

Inland claims after lawful entry

– People who lawfully enter Canada (visa-exempt or with a valid visa) can make inland claims.

– Under Bill C-2, claims would be ineligible if filed more than one year after entry for those who entered after June 24, 2020.

– The proposal is designed to pressure earlier filings and reduce late claims.

These windows—especially the 14‑day and one‑year bars—place tight time pressure on people moving from ICE detention toward Canada. Delays due to travel, family needs, or confusion about the process could close the door if the bill is passed as drafted.

Safe Third Country Agreement: How It Intersects with Detention and Release

The STCA is the hinge rule on the land border: asylum seekers should ask for protection in the first safe country they reach—usually the U.S. in Canada-bound cases. Its general effect is to block most asylum claims at Canadian land ports.

- Exceptions exist (family in Canada, unaccompanied minors, etc.) and can allow a person to present a claim at a port of entry.

- If no exception applies, people sometimes consider irregular entry—an approach Bill C-2 would deter through its 14‑day rule.

For someone in ICE detention, the STCA funnels choices: unless you fit an exception, a land-port claim will usually be unavailable.

IRB Capacity: Backlogs That Shape Lives

- In 2023, Canada received about 140,000 asylum claims; the IRB has seen volumes rise faster than its capacity to finalize decisions.

- Funding boosts have helped but not eliminated the backlog; hearing dates have moved out significantly.

- During long wait periods, families must find housing, enroll children in school, and access health services—often amid stress and uncertainty.

The government’s plan to narrow humanitarian intake to 20,000 in 2025, within an overall target of 500,000 admissions, increases pressure on claim processing and IRB scheduling. Even an accepted claim may take a very long time to resolve.

Step-by-Step Pathway After Release from ICE Detention

There is no Canadian shortcut to pierce U.S. custody. Practically, the sequence looks like:

- Seek release from ICE custody

- Bond, parole, or other release mechanisms under U.S. rules are required.

- U.S. legal counsel is essential to explain options and file necessary requests.

- Until release, Canada’s asylum system remains out of reach.

- Plan the route to Canada

- Consider whether an STCA exception may apply at a port of entry.

- Crossing irregularly exposes you to the 14‑day rule under Bill C-2, so timing and route selection matter.

- Prepare to present the claim

- At ports of entry, officers assess eligibility; eligible claims are referred to the IRB.

- Inland claims follow after entry, but the one‑year bar would matter for those who entered after June 24, 2020.

- Keep legal status current

- A rule change effective May 28, 2025 affects “maintained status”: if an application is refused and a person files a new one, they do not automatically keep status and may need to apply for restoration.

- Prepare for outcomes

- If the IRB grants protection, a path to permanent residence opens.

- If refused, options are limited (humanitarian and compassionate applications, discretionary relief).

- Each step involves paperwork, interviews, and long waits.

Risks, Missteps, and How to Lower Exposure

Key risks

– Waiting too long: The 14‑day and one‑year rules in Bill C-2 could close doors for late filers.

– Crossing irregularly and pausing: Delays after irregular entry can trigger ineligibility or credibility problems.

– Assuming transfer is automatic: There is no program moving detainees from ICE detention into Canada; release in the U.S. is the first gate.

– Losing status without knowing it: After May 28, 2025, a refused applicant who files again may lose maintained status.

– Not tracking the IRB backlog: Long waits affect housing, schooling, and mental health.

How to reduce exposure

– Seek legal advice early in the U.S. and Canada.

– File quickly where possible to avoid time-bar risks.

– Gather and preserve documentation (family ties, identity, travel, evidence of risks).

– Plan for long waits: arrange housing, schooling, and mental health supports.

Stakeholders and Their Current Positions

- Government of Canada (IRCC, IRB, Minister Sean Fraser)

- Responding to record claim numbers and public concern about irregular migration.

- Introduced Bill C-2 to narrow eligibility, speed filings, and expand executive tools.

- Canadian Council for Refugees (CCR)

- Opposes the 2025 cut in humanitarian spaces.

- Urges more protection tools, including broader use of Temporary Resident Permits.

- Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB)

- Facing high workloads and struggles to keep up despite temporary funding.

- U.S. ICE and DHS

- Continue detention and enforcement; no formal channel exists with Canada to transfer detainees into the Canadian asylum system.

Real-Life Scenarios That Show the Stakes

- Mother with two children in ICE detention

- Released after a U.S. bond hearing, she gathers proof of family in Toronto and heads to a land port.

- The STCA family exception is assessed and, if met, the claim is referred to the IRB.

- The family faces a long timeline, temporary housing needs, and school enrollment for children.

- Single man who crossed irregularly, returned to the U.S., detained, then re-entered irregularly

- If he hesitates to file, Bill C-2’s 14‑day rule could make him ineligible.

- Early filing would reduce risk.

- Student who entered late 2021 with a visa and later files inland

- Under Bill C-2, a claim filed more than one year after entry would be ineligible, pushing the student to file quickly.

Timeline Picture: How Long Will It Take?

Processing times depend on two moving parts:

1. Eligibility checks by border or inland officers (including STCA considerations).

2. IRB hearing scheduling and backlog.

With about 140,000 claims in 2023 and continued high volumes, queues are long. While some measures speed simpler cases, volume outpaces capacity. Families should plan for drawn-out waits and arrange housing, schooling, and mental health support with local community groups.

Why Ottawa Is Moving This Way

The government cites heavy claim volumes, long backlogs, and public pressure around irregular crossings to justify Bill C-2 and the smaller humanitarian target of 20,000 in 2025. The stated intent is to:

- Encourage prompt filing,

- Reduce late filings,

- Steer people toward official ports of entry.

Critics argue the plan risks shutting out people who need time to recover from trauma or who struggle to meet tight deadlines after release from ICE detention. They warn that reducing humanitarian spaces while keeping broad immigration targets favors economic streams over protection needs.

Practical Planning for Families and Counsel

- Get U.S. legal help early: release is the first gate; bond or parole plans are crucial.

- Map the route to Canada: gather proof of family ties if an STCA exception may apply.

- File fast: the 14‑day and one‑year bars under Bill C-2 would punish delays.

- Track status: after May 28, 2025, a refused applicant who re-files may lose maintained status and need restoration.

- Plan for the long haul: IRB backlogs mean long waits—secure housing, schooling, and community supports.

The United States–Canada Policy Mix: How It Shapes Choices

- The STCA remains central: Canada and the U.S. rely on it to manage land-border asylum.

- Bill C-2 would add significant time bars and executive powers on top of the STCA.

- For people in ICE detention:

- Canada’s door is not closed, but it is tighter.

- Official ports of entry are safer filing points if an STCA exception applies.

- Irregular entry triggers a 14‑day timer that raises the stakes.

- Late inland claims may be blocked by the one‑year rule.

- Fewer humanitarian spaces in 2025 add pressure to the claim process.

Looking Ahead: What Could Change Next

Several moving pieces could shift the picture:

– Bill C-2 is still progressing through readings and debate. Amendments or court challenges are possible.

– IRB capacity: temporary funding helps, but volumes remain high; delays are likely to persist into 2025.

– Advocacy pressure: groups such as the CCR will push for more protection spaces, faster family reunification, and broader use of Temporary Resident Permits.

– Cross-border coordination: there is still no plan to move people from ICE detention into Canada’s system. Release in the U.S. remains the main first step.

Where to Find Official Rules and Updates

For the latest official instructions on how to claim refugee protection in Canada—at a port of entry or inland—see the Government of Canada’s guidance on claims made inside Canada at: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/refugees/claim-protection-inside-canada.html. This page explains who can claim, where to present a claim, and what happens after referral to the IRB.

Key takeaway: Canada’s door for protection remains open, but it is under strain. The proposed Bill C-2 tightens timelines; the STCA limits who can claim at the land border; and the IRB is working through a heavy caseload. For people coming out of ICE detention, the safest approach is: secure release, assess your STCA options, move quickly to file, and prepare for a long process.

Bottom Line for People in ICE Detention Who May Qualify for Canadian Protection

- First: secure release under U.S. rules—bond or parole—because Canada’s system is inaccessible until release.

- Second: aim to present at an official port of entry if an STCA exception applies; otherwise, be aware of the 14‑day filing risk for irregular entry under Bill C-2.

- Third: file early—late filings (more than one year after entry for certain entrants, or after 14 days for irregular crossings) could be ineligible if the bill passes.

- Fourth: expect long delays—the 140,000 claims in 2023 and ongoing volumes mean lengthy waits for hearings.

- Fifth: monitor your status—after May 28, 2025, a refused application followed by a new filing does not automatically preserve status; restoration may be needed.

- Sixth: keep detailed records—family ties, identity, travel history, and evidence of risks in your home country are essential.

- Finally: seek legal advice in both countries—U.S. counsel to help secure release; Canadian counsel to plan filing route, timing, and evidence.

Canada’s protection system remains accessible but constrained. For people coming out of ICE detention, planning, quick filing where possible, and strong legal support in both countries are the best ways to reduce avoidable harm and preserve the chance to seek safety.

Frequently Asked Questions

This Article in a Nutshell

Canada is tightening asylum access: Bill C-2 adds 14‑day and one‑year bars, cuts humanitarian places to 20,000, and stresses IRB capacity, pressuring detainees released from U.S. ICE to act fast, secure release, and gather legal support to preserve eligibility and navigate long waits for hearings.