The Department of Homeland Security is under intense legal and political pressure after a string of 2025 actions that expand fast‑track removals, allow deporting migrants to third countries without advance notice, and end large parole programs that had given work authorization to tens of thousands.

The shift follows a Supreme Court order on June 23, 2025, that let DHS resume third‑country removals while litigation continues, and a DHS policy effective January 21, 2025, that broadened “expedited removal” nationwide for people who can’t prove two years of continuous presence in the United States.

What the Supreme Court order allows

Under the Supreme Court order, DHS can remove noncitizens to countries other than their own with little or no notice and limited ability to contest the transfer.

- The administration says it has agreements with at least 58 countries to accept such returns.

- In a dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson, warned the ruling empowers the government to “deport anyone anywhere without notice or an opportunity to be heard,” citing due process concerns and safety risks for those sent to unfamiliar countries.

Expanded expedited removal policy

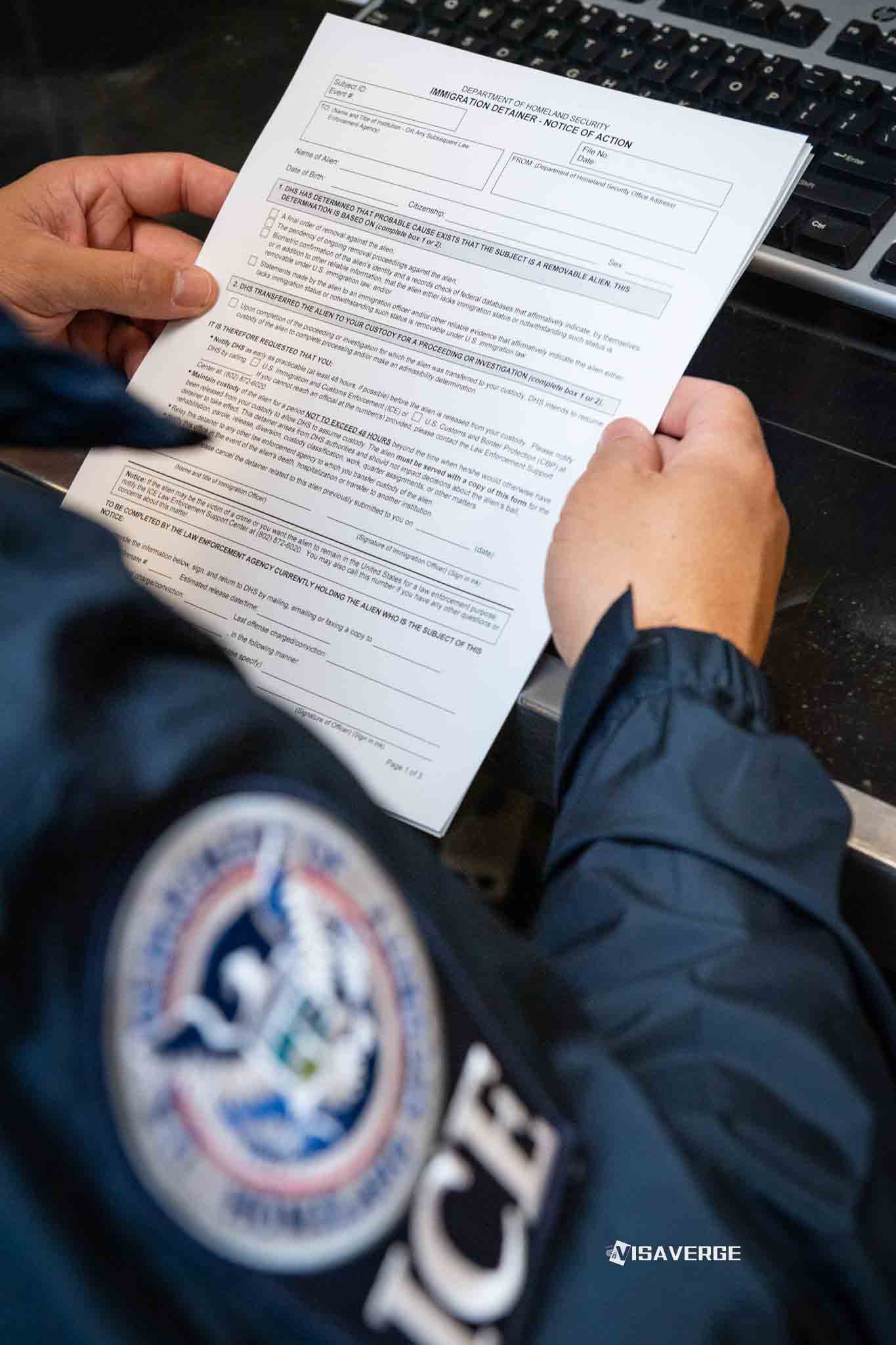

The expanded expedited removal policy — administered by ICE and CBP — now applies nationwide to people unable to show two years of continuous presence, including some who entered by parole.

- People placed in expedited removal typically do not see an immigration judge.

- The only path to a hearing is the credible fear route: a person must state they fear harm if returned and pass a screening interview to seek asylum.

- Otherwise, officers can issue rapid deportation orders, often within days.

CHNV parole termination and work authorization revocation

DHS terminated the CHNV parole programs for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans effective March 25, 2025, and revoked work authorization as of April 24, 2025.

- The Supreme Court removed a preliminary injunction on May 30, 2025, clearing the way for the termination and loss of employment benefits.

- Affected parolees were instructed to return their EADs (work permits) to USCIS.

- New CHNV parole requests are not being processed.

Ongoing litigation and advocacy response

These policy changes have spurred numerous lawsuits and advocacy actions.

- A federal suit filed on March 23, 2025 (DVD v. DHS) challenges DHS’s practice of sending noncitizens to third countries without notice or a chance to assert fear of torture, citing the Fifth Amendment and international law.

- On July 16, 2025, immigrants and advocates filed a class action seeking to stop ICE from arresting people at immigration courts and placing them into fast‑track deportation, arguing this practice chills attendance and violates due process.

- DHS Secretary Kristi Noem is named in recent litigation amid questions about enforcement choices and public communication.

Leading advocacy organizations involved include:

- Democracy Forward

- Immigrant Advocates Response Collaborative

- American Gateways

- National Immigration Project

- ACLU

- National Immigration Litigation Alliance

A separate settlement, J.O.P. v. DHS (finalized November 25, 2024), still protects certain unaccompanied children seeking asylum and set a class membership cut‑off of February 24, 2025. While narrower in scope, that settlement demonstrates that federal courts can still shape parts of the system.

Procurement, contracting, and transparency concerns

Contracting and procurement have drawn criticism as deportation operations scale up.

- Critics accuse DHS of rushing large removal contracts and short‑cutting transparency rules.

- There is no public filing confirming a specific “$915 million deportation contract” lawsuit this year, but plaintiffs and watchdogs say procurement pace has outstripped oversight.

- Analysis by VisaVerge.com indicates the enforcement‑related spending surge is triggering more public‑records requests and legal challenges to force disclosure of who is moving people and under what terms.

How procedures work on the ground

Based on DHS guidance and court filings, current procedures function as follows:

- Expedited removal

- ICE or CBP arrests a person anywhere in the country.

- If the person can’t prove two years of continuous presence, officers place them in expedited removal.

- There is no immigration judge unless the person states fear and passes a credible fear interview.

- If credible fear is approved, the person can pursue asylum; if not, deportation often follows quickly.

- CHNV parole termination

- Parolees received notices that their status and work authorization ended.

- Work permits were revoked on April 24, 2025; people were told to return EAD cards.

- New CHNV parole requests are not being accepted.

- Third‑country removals

- DHS may send a person to a country that is not their own, sometimes with limited notice.

- Opportunities to contest transfers are restricted while lawsuits proceed.

Practical effects and community impact

The practical consequences are sweeping and reach beyond border regions.

- Longtime residents who cannot quickly document two years of presence risk arrest at work, at home, or even in court corridors.

- Advocates report families splitting up as parents weigh attending hearings against the risk of being detained.

- VisaVerge.com reports many asylum seekers feel less safe traveling to court or ICE check‑ins for fear of being placed on fast‑track removal after a brief screening.

The lack of notice and limited access to counsel raise constitutional concerns and risk sending people to harm, critics say. Government officials counter that the actions are necessary to enforce the law and end what they call “catch and release.”

Supporters highlight that President Trump has pledged what he calls the largest deportation program in U.S. history, signaling more resources for arrests and removals. They argue that the Supreme Court’s orders and DHS policies restore control and deter unlawful entry. Dissenting justices and advocates emphasize due process and safety concerns.

Practical advice for affected families and individuals

Legal groups advise families to keep proof of presence, identity, and family ties within easy reach. Useful documents include:

- School records

- Lease agreements

- Pay stubs

- Medical bills

- Dated mail addressed to the person

In a credible fear screening, a clear statement explaining why return would be dangerous is important. Additional recommendations:

- Ask for an interpreter in your best language.

- Request to speak with a lawyer.

Note: These steps do not guarantee protection, but they may preserve legal options.

Broader implications and questions

Policy watchers say 2025 marks the broadest use of expedited removal since its creation in 1996. The scale of third‑country transfers — with 58 countries reportedly participating — raises new questions:

- How does DHS choose destinations?

- What safety checks are in place for receiving countries?

- What protections exist if a deportee faces harm after transfer?

The Supreme Court and lower courts will likely continue to hear arguments as challenges proceed.

Where to find official updates and help

Amid sparse but important official channels, readers can check DHS announcements and contacts at https://www.dhs.gov for policy notices.

Community groups and legal aid organizations continue to file suits and publish guidance, but access to counsel remains limited during fast‑track processes.

Human stakes

The policies have immediate, personal consequences:

- A father with mixed‑status children may skip a court date, fearing arrest.

- A CHNV parolee who established residency and employment over two years now faces job loss after work papers were pulled.

- A young woman from a conflict zone might be flown to a third country she has never visited, with little chance to speak to a judge.

These scenarios illustrate the real‑world outcomes as DHS implements accelerated deportation policies while courts, Congress, and communities struggle to respond.

This Article in a Nutshell

June 2025 rulings and DHS policies accelerated deportations, widening expedited removal and third‑country transfers. CHNV parole ended, stripping work permits. Lawsuits challenge notices, due process, and contracting transparency, while advocates advise keeping two‑year proof and preparing credible fear statements to preserve possible asylum protections during fast‑track removals.