- U.S. government officials revoked over 100,000 visas recently due to enhanced continuous vetting and security screening.

- Visa revocation differs from deportation; it cancels the travel document but not necessarily current lawful status.

- Travelers should verify I-94 records and consult legal counsel before leaving the U.S. if a revocation occurs.

(UNITED STATES) — With reported visa revocations topping 100,000 visas in roughly a year, many travelers, students, and family visitors are asking the same question: what happens when the U.S. government cancels a visa after it was already issued, and what can you do next?

this explainer walks through what visa revocation accomplishes, who is most affected (including student visas and family visitors), and the practical steps to confirm a revocation and respond in a way that protects your immigration options.

1) What a visa revocation is — and why the current surge matters

A U.S. visa is generally a travel document that allows you to appear at a port of entry and request admission. It is not, by itself, lawful “status” inside the United States.

That difference is central to why revocations can be so disruptive. Visa revocation means the Department of State (DOS) cancels an already-issued visa foil or electronic visa record.

Revocation is different from other immigration actions:

- Visa denial: a consular officer refuses a new visa application under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), often INA § 214(b) or INA § 212(a).

- Removal (deportation): DHS seeks to remove someone from the U.S. through immigration court (EOIR) or expedited processes. Visa revocation alone is not a removal order.

In official statements released in the past two days, DOS and DHS described a major increase in cancellations, framed as a sustained operational shift tied to “continuous vetting,” not a one-time sweep.

Headline numbers matter because revocation can stop travel immediately. It can also affect a person currently in the U.S. who later needs to re-enter.

2) What officials have said — and what not to assume from it

DOS public messaging attributed the increase to public safety, compliance, and security screening. In a Jan. 12, 2026 post, the State Department said it revoked over 100,000 visas and referenced several thousand revocations involving student visas and certain employment categories.

A deputy spokesperson also referenced a “Continuous Vetting Center” and described ongoing screening after visa issuance. Secretary of State Marco Rubio, in recent remarks, described revocations and denials as tools used when conduct is viewed as contrary to U.S. interests, including conduct occurring after admission.

Operationally, these statements signal a posture in which a visa is treated as continuously reviewable. They do not mean every arrest triggers revocation, or that every revocation leads to removal.

Warning: A revoked visa can block boarding or admission even if you previously entered lawfully. Do not assume “I’m already in the U.S.” means travel is safe.

3) Who is most affected (by category) — and where scrutiny shows up

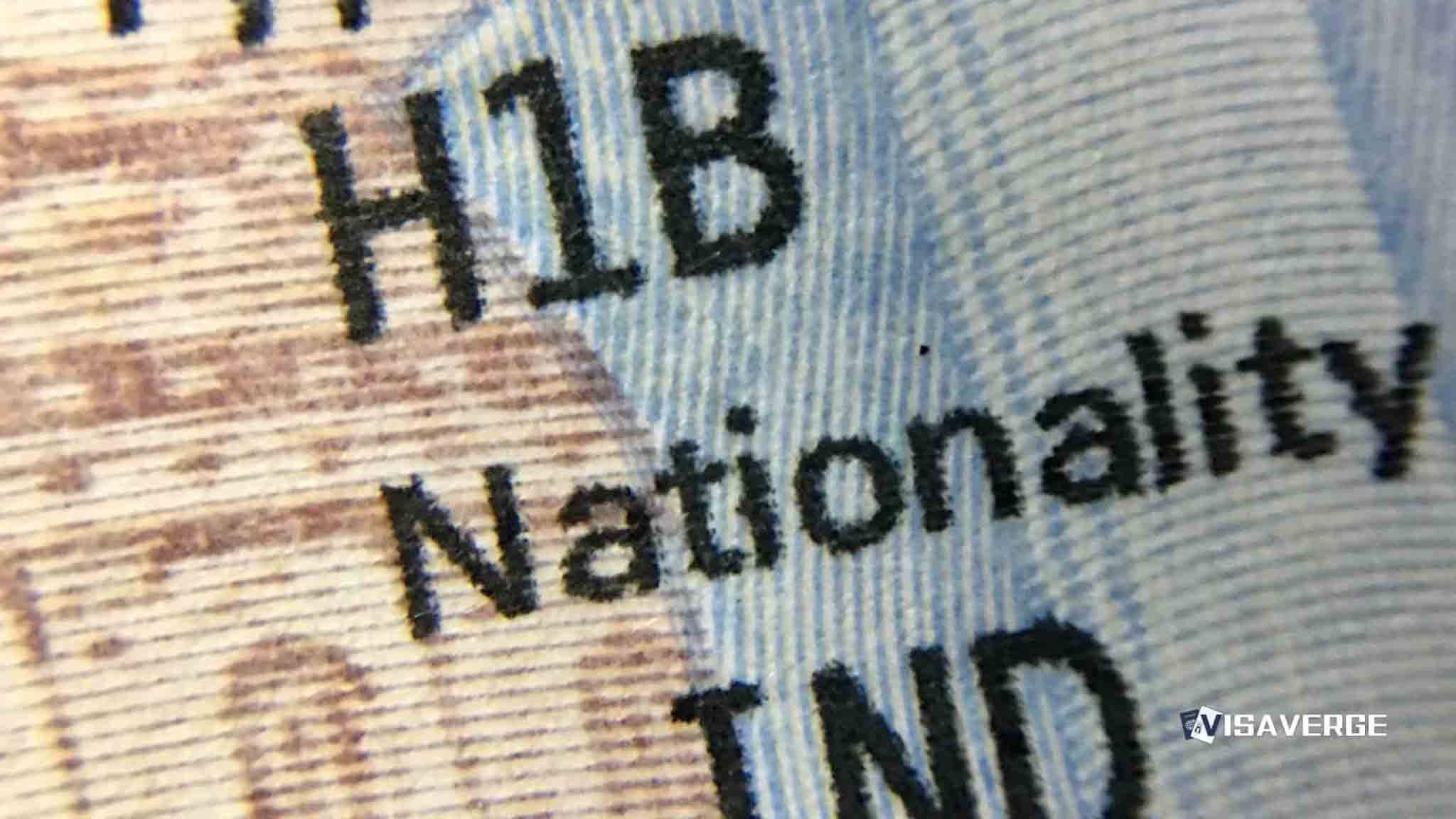

The reported totals reflect a sharp rise compared to the prior year. The largest share was described as business/tourist visas, commonly associated with overstay concerns.

Officials also highlighted revocations affecting student visas and certain specialized worker categories. What “majority share” means in practical terms: B-1/B-2 visitors may face heightened scrutiny at consular renewal, airline check-in, and the port of entry.

Students and workers may face scrutiny both at visa stamping and through post-issuance review tied to compliance or law enforcement data.

Typical checkpoints where revocation becomes visible include:

- Before travel: airline boarding systems may reflect invalid visas.

- At entry: CBP officers may see revocation notes and refuse admission.

- At renewal: consular officers may treat the prior revocation as derogatory history.

4) Leading causes and risk factors that can trigger revocation

The government’s cited drivers can be translated into concrete risk areas. Outcomes vary widely and depend on the person’s location, current status, and the ground of inadmissibility or removability implicated under INA § 212(a) or INA § 237(a).

The most commonly described areas include:

- Overstays and status violations (often B-1/B-2). Overstays can be detected through travel records and other compliance checks. Overstay history can also trigger INA § 212(a)(9)(B) unlawful presence bars in some cases, complicating future visa issuance.

- Arrests and criminal allegations (including DUI and assault). Many revocations are described as tied to arrests, including DUI and assault-related encounters. Immigration consequences can attach to conduct and arrests, not only convictions, depending on the government’s information and the legal theory used.

- Security-related or “national interest” grounds. Officials referenced a smaller subset tied to security or ideological concerns. Social media and public statements can become part of an adjudicatory record; context, translation, and intent can matter.

A visa can be revoked even while a criminal case is pending. The next immigration step depends on whether DHS also acts on the person’s status and whether a ground of inadmissibility or removability is implicated.

5) What changed operationally: continuous vetting, “voiding,” and prudential revocation

The key mechanics described by officials fit a broader concept: visas are revocable, and the government may revisit eligibility after issuance.

- Continuous vetting: Agencies may review new information after issuance, including arrest reports and compliance indicators.

- Electronic “voiding”: A revocation may appear in government systems immediately, even if the visa foil remains in a passport.

- Prudential revocation: DOS can revoke based on credible derogatory information, including arrest data, before a criminal case ends.

Social media screening should be understood as part of the overall evidentiary picture. Posts that appear to endorse violence, illegal activity, or prohibited organizations may draw attention. Misattributed posts and sarcasm also create risk, because adjudicators may read content without full context.

Do not attempt to “fix” perceived problems by deleting accounts or altering past entries during an active review. Inconsistent explanations can create separate credibility issues.

6) Practical consequences: outside the U.S. vs. inside the U.S.

If you are outside the United States

A revoked visa can prevent boarding or lead to refusal at the port of entry. Your next step is typically a new visa application, which may be harder because the prior revocation becomes part of the record.

If you are inside the United States

Revocation of the visa stamp does not automatically cancel lawful status granted by DHS. For example, an F-1 student may still be in valid F-1 status even with a revoked visa, if SEVIS and school enrollment remain compliant.

An H-1B worker may still have valid petition-based status, if the I-94 and approval remain valid. But travel becomes risky: if you depart, you generally must obtain a new visa to return.

Student-specific issues (F-1/J-1): Students should involve the Designated School Official (DSO) quickly. SEVIS termination, if it occurs, can place someone out of status and increase enforcement exposure.

Worker-specific issues (H-1B/L-1/O-1): Workers should coordinate with counsel and the employer. Employer compliance records and petition validity may matter. Even if USCIS approved the petition, a revoked visa can still block re-entry.

If you receive a consular notice of revocation or a CBP refusal, collect records immediately. Waiting can make it harder to obtain police reports, court dockets, and I-94 history.

7) Step-by-step: how to verify a revocation and respond

The following steps outline document gathering, assessment, and practical actions to stabilize status or pursue a new visa.

Step 1 — Confirm what was actually revoked (visa vs. status)

Documents to gather:

- Passport biographic page and visa foil (if any)

- Most recent I-94 record (download from CBP)

- Any email or letter from DOS or the consulate

- All USCIS approval notices (Form I-797) if you are a worker

- For students: SEVIS/DSO communications and school enrollment proof

Decision point: If your I-94 is still valid and you remain compliant, you may still be in status even with a revoked visa.

Step 2 — Request and organize the underlying incident record, if any

Documents to gather:

- Certified court disposition for any case

- Police report or arrest record (if available)

- Proof of sentence completion, programs, or dismissals

- Attorney letter from criminal defense counsel, if applicable

Common mistake: Relying on a verbal summary of the case. Consular review often turns on the exact statute and disposition.

Step 3 — Assess admissibility and future visa eligibility

This is the legal “triage” step. Grounds may include criminal-related inadmissibility under INA § 212(a)(2), fraud under INA § 212(a)(6)(C), or unlawful presence under INA § 212(a)(9)(B).

Decision point: Some issues may be waivable; others may not be. Waivers depend on the visa category and facts.

Step 4 — If you are in the U.S., stabilize status before travel

Possible actions may include:

- For students: DSO-led SEVIS remedies, if available

- For workers: extension or amendment planning with employer, if needed

- For family visitors: avoiding overstay, and documenting compliance

Common mistake: Leaving the U.S. assuming you can “sort it out” at stamping. Revocation often makes stamping unpredictable.

Step 5 — Apply for a new visa, if required

Typical required items:

- Form DS-160 (most nonimmigrant categories)

- Passport, photo, fee receipt, interview confirmation

- Prior visa pages and refusal/revocation documentation

- Court dispositions and police records (where relevant)

- For students: Form I-20 and financial evidence

- For workers: Form I-797, employment verification letter, pay records

Timelines and delays: Appointment backlogs vary by post. Administrative processing can add weeks or months, especially where derogatory information is involved.

Step 6 — Consider FOIA for clarity in complex cases

If facts are unclear, a Freedom of Information Act request may help. Depending on the situation, FOIA may be directed to DOS, DHS components, or USCIS.

Timing can be slow, so FOIA is usually not a last-minute travel fix.

Traveling while a revocation or derogatory flag is unresolved can trigger refusal of admission and expedited return. Speak with counsel before departure.

Where to check official information

Use official government sources to verify broad policy statements and to avoid misinformation. Prioritize direct .gov pages, press releases, and case-specific notices.

Keep complete copies of notices, DS-160 confirmations, and all court records. Those documents often control what happens next. For readers facing arrest-related revocation issues, attorney help is especially important because criminal statutes and immigration consequences do not always align cleanly, and circuit law can vary.

The following links point to official resources and referral tools:

Legal Disclaimer: This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.

U.S. authorities have revoked over 100,000 visas recently, signaling a major operational shift toward continuous vetting. While revocation cancels travel documents, it differs from deportation. Affected individuals, including students and H-1B workers, must distinguish between visa validity and lawful status. Experts recommend gathering all legal documentation and seeking counsel before attempting international travel, as re-entry requires navigating a complex new application process.