(BUDAPEST, HUNGARY) — A U.S. visa is not a guaranteed right, and the U.S. government can withdraw it when officials conclude a traveler no longer qualifies or the trip no longer serves U.S. interests.

That principle was underscored Tuesday, February 17, 2026, when Secretary of State Marco Rubio described a U.S. visa as a discretionary, temporary permission—not an entitlement—and warned that withdrawal (cancellation or revocation) can occur quickly when “new information” or later conduct changes the government’s assessment. For readers, the practical question is not only “Can my visa be issued?” but also “Can it be canceled after it is issued, and what rights do I actually have if that happens?”

This rights guide explains the legal framework behind visa discretion, cancellation and revocation, enhanced vetting, and what travelers and applicants can do to protect themselves and respond if problems arise.

1) Overview: A U.S. visa is a privilege—and it is different from status

The right at issue: Many noncitizens have the right to apply for a visa and to be treated according to the procedures U.S. law provides. But most foreign nationals do not have a constitutional “right” to receive a visa or to enter the United States.

Visa vs. admission vs. status

It helps to separate three concepts that are often conflated:

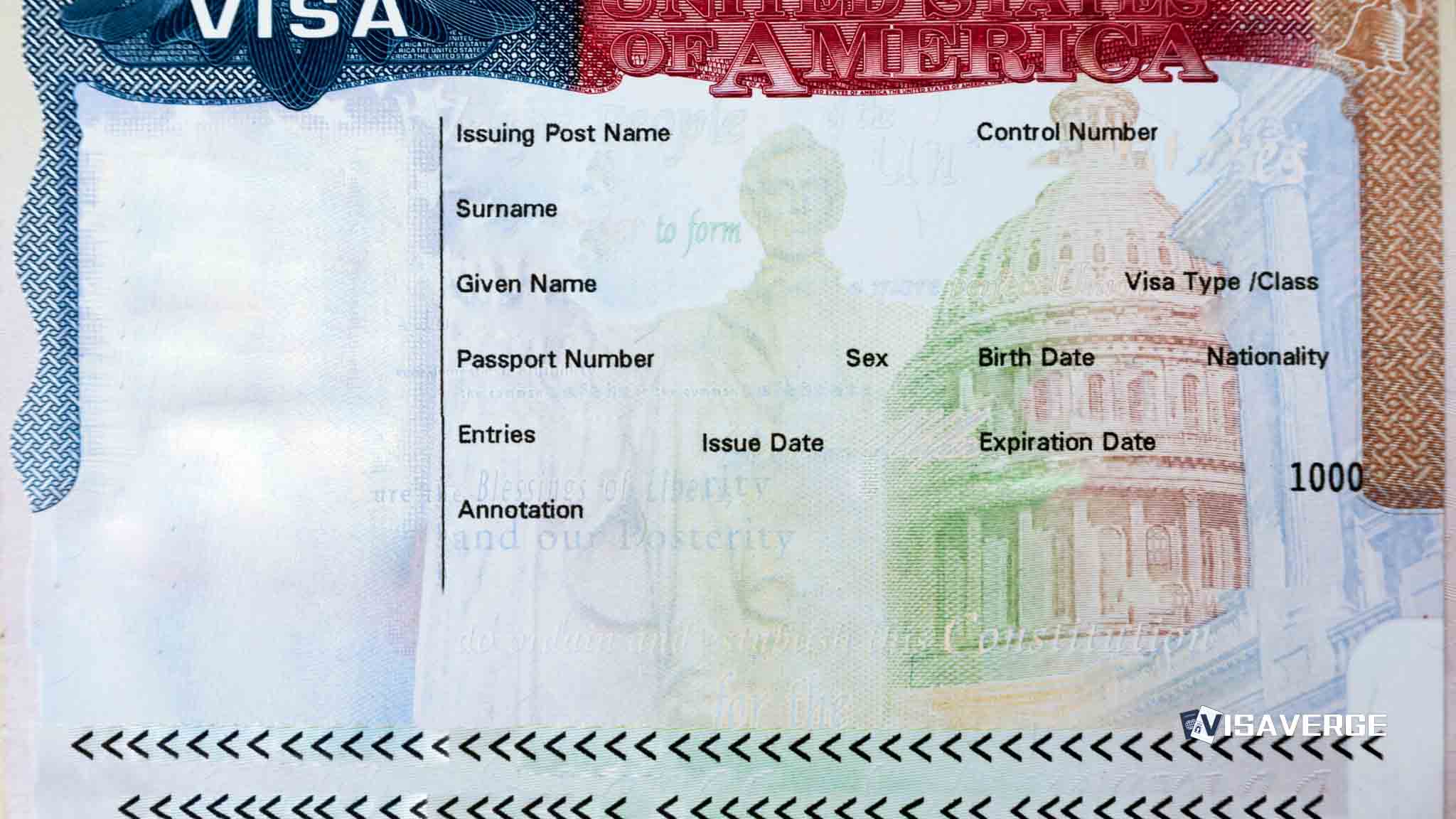

- Visa (DOS/consulate): A visa is an entry document placed in a passport. It generally allows a person to seek admission at a U.S. port of entry. Visa issuance is handled by the U.S. Department of State (DOS).

- Admission (CBP/port of entry): A visa does not guarantee admission. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) decides admission at the airport or land border.

- Immigration status (after entry): If admitted, a person is granted a status (for example, B-2 tourist or F-1 student) and a period of authorized stay. Status rules are governed by the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) and regulations, and often administered by USCIS for benefits. See uscis.gov.

What “cancellation” and “revocation” mean

In everyday terms, “visa withdrawal” can show up in several ways:

- Consular revocation/cancellation: DOS can revoke a visa already issued. It may happen with little notice.

- Carrier boarding problems: Airlines typically rely on government systems. If a visa is canceled, boarding can be denied.

- Port-of-entry action: Even with a valid visa, CBP can refuse admission if it finds inadmissibility under INA § 212(a) or concludes the traveler is not a bona fide visitor.

At a high level, the law gives the executive branch broad discretion in visa decisions tied to national security and foreign policy. That discretion is one reason visa disputes are often hard to challenge in court.

2) Official statements and quotes (Feb. 17, 2026): what “temporary and conditional” means in practice

In Budapest, Rubio framed visas for students, tourists, and journalists as temporary and conditional, and emphasized the government’s willingness to act quickly when later facts or conduct change the picture. He also suggested that some prior revocations would not have been necessary if the government had known an applicant’s intentions earlier.

The key practical takeaways for applicants and travelers are procedural, not political:

- “New information” can be broad. It can include facts later discovered about the application, inconsistent identity data, or information from law enforcement or other agencies.

- Later behavior can matter. Conduct after issuance may trigger review. Examples can include violating status conditions, working without authorization, or conduct the government views as relevant to public order or security.

- Timing can be abrupt. Revocation may occur close to a flight date, during a trip, or at a visa renewal attempt.

Warning: A valid visa does not guarantee entry. CBP can still refuse admission, and travelers may have limited time to consult counsel once secondary inspection begins.

3) Key policy details and statistics: what readers are hearing—and how it shows up in real cases

Several policy actions discussed publicly in recent months can affect both first-time applicants and repeat travelers. The underlying legal mechanics are not always visible to the public, but the consequences often are.

“Suspended processing” of immigrant visas (procedural meaning)

Reports describe an immigrant-visa processing pause affecting citizens of many countries, tied to “public charge” concerns. When DOS “suspends processing,” it typically means:

- Appointments may be delayed or unavailable, even for documentarily qualified cases.

- Cases may be held in administrative limbo, with little predictability.

- Medical exams and police certificates may expire, forcing updates.

- Family separation and employment start dates may be pushed back.

A pause does not necessarily mean a permanent denial. But it can create extended delay and uncertainty, especially for family- and employment-based immigrant visa applicants.

Deadline/Timing Note: Implementation dates and the full number of affected countries are summarized in the official materials. Check DOS updates before scheduling medical exams or selling property.

Reported visa cancellations tied to certain political activities

Public reporting also described hundreds of visa cancellations associated with certain political activities. Whatever the label used publicly, the mechanisms that commonly lead to cancellations are familiar:

- Consular action: DOS may revoke under its authorities and notify the applicant, sometimes after the fact.

- Systems updates: Airlines may receive a “no board” message if the visa is no longer valid.

- CBP inspection: Even if the visa remains valid, CBP may question the traveler’s intent and admissibility.

Importantly, the grounds for cancellation can range from classic issues (fraud, ineligibility, overstay history) to broader discretionary assessments framed as public order or national interest.

Expanded social media and online presence vetting

DOS has increasingly required disclosure of social media identifiers, and consular officers may review online presence for identity consistency and credibility. In practice, applicants most often run into trouble when:

- Identity details do not match across passports, DS-160s, resumes, and online profiles.

- Prior travel history, employment history, or school history appears inconsistent.

- Online posts suggest an intent inconsistent with the visa category (for example, intent to work while applying for a visitor visa).

Enhanced vetting can also lengthen interviews and produce 221(g) refusals for administrative processing under INA § 221(g). A 221(g) is not a final denial. It usually means the case is pending additional review or documents.

Targeted restrictions aimed at foreign officials

Separately, Rubio described visa bans aimed at certain foreign officials connected to censorship or targeting U.S. tech companies. This type of restriction is distinct from individualized applicant vetting. It is often rooted in foreign policy tools and can apply based on official role or conduct, not the typical tourist or student factors.

4) Context and significance: the “national interest” frame, and limits on challenges

“National interest” as a discretionary concept

Immigration law contains many places where the government may consider broad factors, including security and foreign policy. In visa adjudication, those considerations can influence:

- Whether a visa is issued at all.

- Whether a visa is revoked after issuance.

- How much scrutiny a case receives during administrative processing.

Traditional bases vs. subjective assessments

In many cases, visa problems still arise from traditional, fact-based issues, including:

- Fraud or misrepresentation (often tied to INA § 212(a)(6)(C)(i)).

- Prior overstays or unlawful presence (INA § 212(a)(9)).

- Criminal grounds (INA § 212(a)(2)).

- Status violations (working without authorization, violating F-1 rules, etc.).

What readers are hearing now is an emphasis on more subjective assessments, such as public order or foreign policy concerns. Those assessments may be harder for applicants to predict, and harder to rebut quickly.

Why appeals can be limited

Many visa decisions occur outside the United States at consulates. As a general rule, courts often give significant deference to consular decisions, and there may be limited formal appeal rights for a refused or revoked visa. That is one reason prevention—accurate filings, consistent records, and careful travel planning—matters.

Warning: Do not assume you can “appeal” a visa revocation on a travel timeline. In many cases, the fastest path is a new application with corrected evidence and legal guidance.

5) Impact on individuals: how students, journalists, tourists, and immigrants can exercise their rights

This section focuses on practical steps—how to protect yourself, how to respond at the consulate or port of entry, and how rights can be lost through avoidable mistakes.

Who has these rights?

- U.S. citizens: Citizens have constitutional rights to enter the U.S., but their foreign family members do not automatically gain visa rights.

- Lawful permanent residents (LPRs): LPRs generally have a strong right to return, but can face issues after long trips or certain criminal conduct.

- Visa holders and applicants abroad: They typically have the right to apply and to be considered under the INA and regulations, but not a right to issuance.

- Undocumented individuals inside the U.S.: They may have due process rights in removal proceedings (EOIR), but that is different from visa issuance abroad.

How to exercise your rights in practice (consulate and travel)

- Prepare consistent records. Ensure your DS-160/DS-260, CV, school or employment letters, and online profiles match on dates, names, and roles.

- Disclose what is required, accurately. Omissions can be treated as misrepresentation.

- Bring category-specific proof.

- Tourists: strong ties, credible itinerary, ability to pay.

- Students: I-20 details, funding, academic plan, and compliance history.

- Journalists: assignment letters, employer details, and clear purpose.

- Plan for delays. If you receive a 221(g), follow the exact document instructions and avoid repeated inquiries that do not add information.

Common ways rights are waived or lost

- Signing statements you do not understand at the border, including withdrawal of application for admission.

- Volunteering inconsistent explanations in secondary inspection.

- Working on the wrong status or violating conditions of stay.

- Reapplying without fixing prior inconsistencies, which can compound credibility issues.

What happens if your visa is canceled or revoked?

- Before travel: You may be denied boarding. Contact the consulate’s visa unit and consult counsel before rebooking.

- During travel or at arrival: CBP may send you to secondary inspection. You may be allowed to withdraw your application for admission or be refused entry.

- After admission: Visa revocation can still affect future travel and renewals, and could trigger scrutiny of status compliance.

If you are in secondary inspection, you can ask to speak with an attorney, but access and timing can be limited at ports of entry. If you have medical needs or fear return, tell the officer clearly.

Warning: If you fear harm if returned, say so plainly and immediately. Different legal standards may apply for protection claims, and timing can matter.

Responding to delays from multi-country processing pauses

For immigrant visa cases affected by processing suspensions, the most practical steps often include:

- Monitoring DOS updates and the specific embassy’s page.

- Keeping civil documents current.

- Coordinating with petitioners and employers on revised timelines.

- Consulting an attorney if there is an urgent humanitarian or medical factor, or if litigation or injunctions affect implementation.

6) Official sources and where to verify changes

For visa rules and real-time updates, prioritize primary sources:

- U.S. Department of State (DOS): travel.state.gov and state.gov for press statements and visa policy announcements.

- Federal Register: federalregister.gov for executive actions and implementing rules.

- CBP: cbp.gov for admission, inspections, and traveler information.

- USCIS: uscis.gov for many domestic filings, extensions, changes of status, and immigration benefits.

Before booking travel, verify whether there are appointment pauses, enhanced vetting steps, or category-specific constraints at your consulate. Also confirm whether your visa category has special documentary requirements.

If you believe your rights were violated—such as being pressured to sign a document you did not understand, or being treated discriminatorily—write down names (if available), badge numbers, timestamps, and what was said. Preserve copies of all paperwork and electronic communications. Then consult a qualified immigration attorney promptly.

For legal help:

- AILA Lawyer Referral: AILA Lawyer Referral

⚖️ Legal Disclaimer: This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.