Section 1: Case background and timeline

A federal district judge ordered hearings or meaningful proceedings for Venezuelan migrants deported under the Alien Enemies Act, but the DOJ counters that no additional due process is owed and threatens higher-court intervention. That clash now sits at the center of a fast-moving separation-of-powers fight in Washington, D.C., with direct consequences for Venezuelans removed under a rarely used wartime statute.

Spring 2025 set the factual stage. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) carried out removals of Venezuelan nationals under the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 rather than through the usual Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) system. Summer 2025 brought a twist: the group later returned to Venezuela through an exchange arrangement, leaving them outside U.S. custody while litigation continued in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia (D.D.C.).

Late 2025, Chief Judge James Boasberg concluded the government’s approach lacked basic procedural safeguards. Early 2026, the Department of Justice (DOJ) told the court those safeguards are not required under the Alien Enemies Act and cannot be ordered in any workable way. A hard line followed. So did an explicit warning that the executive branch would ask higher courts to step in.

Three institutions control different levers in this dispute. DHS controls removals and detention logistics. DOJ represents the executive branch in court and defends the wartime framing. D.D.C. controls judicial review, including whether any process must be provided and how court orders can be enforced when the affected people are abroad.

At bottom, the conflict is simple to state and hard to resolve: when the executive invokes wartime authority to remove noncitizens, how much can a federal court require in terms of process, and how far can a court go to enforce that requirement?

Section 2: Key facts and policy details

Chief Judge James Boasberg’s case focuses on 252 Venezuelan migrants removed in March 2025. DHS sent them to the CECOT prison in El Salvador, a maximum-security facility. By July 2025, the same group was back in Venezuela through an exchange, and they are now located there rather than in U.S. custody.

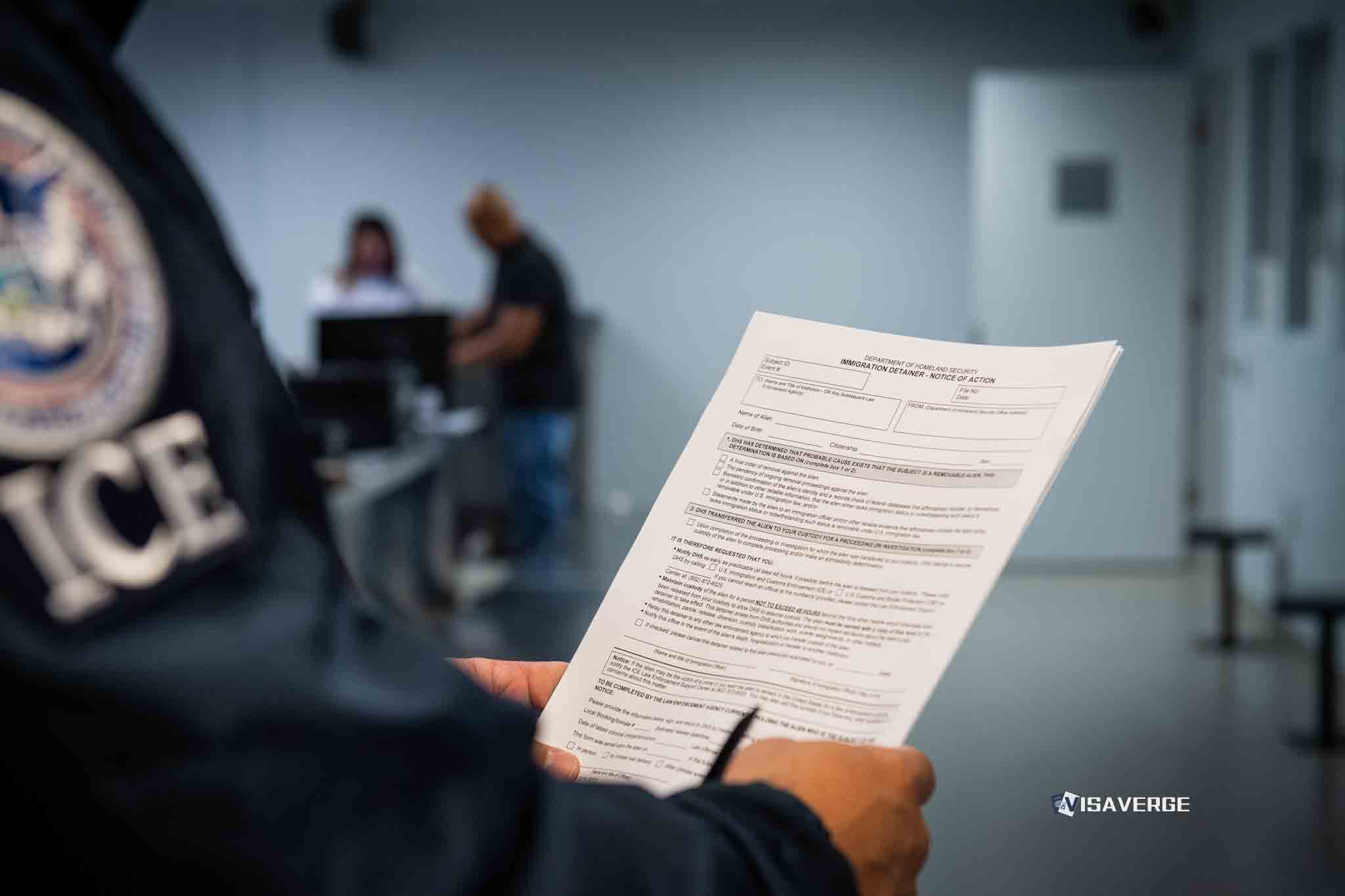

DOJ and DHS justify the use of the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 as a wartime measure. The administration’s public framing treats Tren de Aragua as an invading or hostile proxy force connected to Nicolás Maduro’s regime. That framing matters because the Alien Enemies Act is not the INA. It is a wartime statute that the executive branch argues can operate outside the ordinary immigration court pathway.

Under the INA, removals commonly involve immigration court hearings, statutory defenses, and asylum screening processes that occur within defined procedural lanes. By contrast, Alien Enemies Act removals, as DOJ has argued them, are executive actions tied to national-security determinations. That difference drives the present dispute over what procedural protections still apply.

December 22, 2025 brought a direct judicial order. Chief Judge James Boasberg required the government to provide hearings or “meaningful proceedings” for the removed Venezuelans. In functional terms, that meant a chance to contest the government’s basis for treating them as “alien enemies,” plus access to a process where a neutral decision-maker could review the designation.

February 2026 brought DOJ’s rejection of that structure. DOJ argued the court could not force the executive to return the group to the United States for hearings. DOJ also argued the court could not require “meaningful proceedings” from abroad in a way that is feasible, given security and operational constraints and the group’s location outside U.S. custody.

DOJ’s filing also tied logistics to national security. The department pointed to operational limits following the U.S. military’s recent capture of Nicolás Maduro, arguing the court’s remedies collide with current security conditions and executive control over sensitive operations.

Table 1: Key actors and roles in the dispute

| Actor/Agency | Role in case | Authority claimed or exercised | Recent public statements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Department of Justice (DOJ) | Defends the removals in court; contests court-ordered procedures | Argues Alien Enemies Act authority permits removals without added due process; seeks to limit judicial remedies | Court filing dated February 6, 2026 argues the government owes “no additional due process at all” and would seek higher-court intervention |

| Department of Homeland Security (DHS) | Executes removals; controls detention and transfer logistics | Implements removals under asserted wartime authority; manages custody and transfer pathways | A DHS spokeswoman criticized the district court’s order after December 22, 2025 |

| U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia (D.D.C.) | Oversees judicial review and remedies | Evaluates constitutional and statutory limits; orders hearings or meaningful proceedings | Chief Judge James Boasberg ruled on December 22, 2025 that due process was denied |

| Attorney General Pamela Bondi | Senior DOJ official; public messenger for executive-branch position | Frames removals as tied to public safety and presidential power | March 2025 statement criticized a court-ordered halt and defended executive authority |

| Tren de Aragua | Central factual predicate for the “enemy” designation | Government frames the group as a hostile proxy force | Named by executive officials in national-security framing |

| Nicolás Maduro | Foreign leader referenced in the proxy-force theory | DOJ points to geopolitics and security conditions | Referenced in DOJ’s national-security justification tied to operational constraints |

Section 3: Official statements and quotes

DOJ’s February 6, 2026 filing stakes out a categorical view of process. Government lawyers said the administration “owes the migrants no additional due process at all.” They also warned that if the district court orders otherwise, DOJ would “promptly seek intervention from the higher courts,” signaling potential appeals to the D.C. Circuit or the Supreme Court.

Attorney General Pamela Bondi previewed the administration’s broader messaging in March 2025 after litigation temporarily halted deportations. In a DOJ press statement, she criticized a D.C. judge for “support[ing] Tren de Aragua terrorists” and argued the order “disregards well-established authority regarding President Trump’s power.” She added that DOJ was “undeterred.” (DOJ statement: Statement from Attorney General Pamela Bondi on federal judge blocking deportations)

DHS messaging has been blunter about the court’s role. After the December 22, 2025 order, a DHS spokeswoman, Tricia McLaughlin, said Chief Judge James Boasberg was “way over his skis” and claimed appellate courts had “shut [him] down” in the case.

Two distinctions matter for readers tracking developments. First, statements in a court filing are legal positions that can be revised as litigation shifts. Second, agency press statements often defend policy and political accountability, but they do not substitute for what a court ultimately orders or what a higher court permits.

Section 4: Legal and constitutional implications

Alien Enemies Act litigation often turns into a debate about baseline constitutional protections. Due process is not a single rule. It is a set of requirements that can change with context, including national security and custody status.

Under the INA, noncitizens in removal proceedings typically receive notice, a hearing framework in immigration court, and defined opportunities to raise defenses like asylum or protection-based claims. Alien Enemies Act removals, as DOJ frames them, sit in a different category. DOJ argues that once the executive invokes wartime authority, standard INA processes do not control, and judicial review should be narrow.

Readers will hear several legal terms as the case moves. Habeas corpus refers to a court’s authority to review detention or restraint and to order relief in some circumstances. Separation of powers describes boundaries between executive action and judicial oversight. Scope of review is the practical question: can a judge examine the factual basis for branding someone an “alien enemy,” or only confirm that the executive made a formal wartime determination?

Chief Judge James Boasberg’s order uses a phrase that sits between full trial rights and no review at all: “meaningful proceedings.” In many federal contexts, “meaningful” implies notice of the grounds, a real chance to contest them, and access to counsel where feasible. It can also require a record that can be reviewed. Still, the precise content can vary, especially when the executive claims national-security privilege or relies on classified material.

Beyond the 252 Venezuelan migrants, the case could shape a template. A ruling that sharply limits judicial review might encourage future reliance on alternative statutory authorities instead of INA pathways, especially in fast-moving security situations.

⚠️ DOJ argues that granting hearings would be “legally impossible or practically unworkable” due to national security and operational constraints; readers should watch for higher-court involvement

Section 5: Impact on affected individuals

Process is not an abstract demand for paperwork. It is the main tool for correcting errors.

Without a formal hearing, a Venezuelan national labeled as tied to Tren de Aragua may have little chance to contest mistaken identity, disputed gang affiliation, or the accuracy of the government’s evidence. That problem grows when the evidence is sealed, classified, or reduced to indirect indicators. Tattoos and social media claims, for example, can become proxies in enforcement decisions, and a hearing is where such claims are tested.

Geography complicates everything. Because the group is currently in Venezuela, communication with lawyers, access to records, and the ability to sign declarations can be difficult. Even when counsel is available, meaningful attorney-client work often depends on secure contact, reliable documentation, and a process that allows submissions to be considered by a neutral decision-maker.

Safety concerns can also rise when a person is publicly described as a gang member. Labels can affect personal security, employability, and interactions with local authorities. A lack of process can make it harder to correct the label, which can shape downstream risks long after removal.

Family separation is another practical consequence. If a person is removed outside INA pathways, family-based relief options and procedural pauses that sometimes occur in immigration court may not be available in the same way. The result can be rapid removal without the usual chance to present humanitarian claims.

Section 6: Official government sources and references

Primary sources will drive the next phase of this dispute. Court filings show what DOJ is asking a judge to do, what facts the government is asserting, and what remedies it says a court cannot order. Agency statements from DOJ and DHS reveal the executive branch’s public posture, but they should be read alongside the actual filings.

USCIS materials matter for a different reason. While USCIS does not run immigration court, it does administer humanitarian programs and publishes alerts that signal policy shifts affecting Venezuelans already in the United States. As of early February 2026, USCIS posted an “Update on TPS Venezuela and Related Litigation” on USCIS. That notice does not resolve the Alien Enemies Act fight, but it shows how legal uncertainty can spill into humanitarian status categories and planning for Venezuelan nationals.

Federal Register notices can also shape expectations because they can formalize program terminations, redesignations, or effective dates for protections like Temporary Protected Status. Those notices are not the same as a DOJ litigation argument. They can carry binding administrative effect when properly issued.

Readers tracking the case should save document versions. A single changed phrase in a filing can shift what a court is being asked to order. PDFs, docket entries, and archived agency notices help when timelines are disputed.

✅ If you are tracking this case, verify the latest court filings and agency statements through DOJ and DHS primary sources; note any changes to treatment of Venezuelan nationals under wartime authority

Reporting involves a legal and constitutional dispute with high-stakes implications for noncitizens and national security policy.

Content reflects ongoing litigation and evolving agency positions; readers should consult primary sources for the latest filings.