(TURKEY) Turkey is no longer regarded as a safe haven for Uyghurs after a sharp shift in migration policy that has led to sweeping residency cancellations, the use of restriction codes that label people security threats, and a growing risk of deportation. Lawyers and community advocates say the change, unfolding as Ankara’s ties with Beijing warm and amid a broader anti-immigration crackdown at home, has upended the lives of families who for years believed they had found protection.

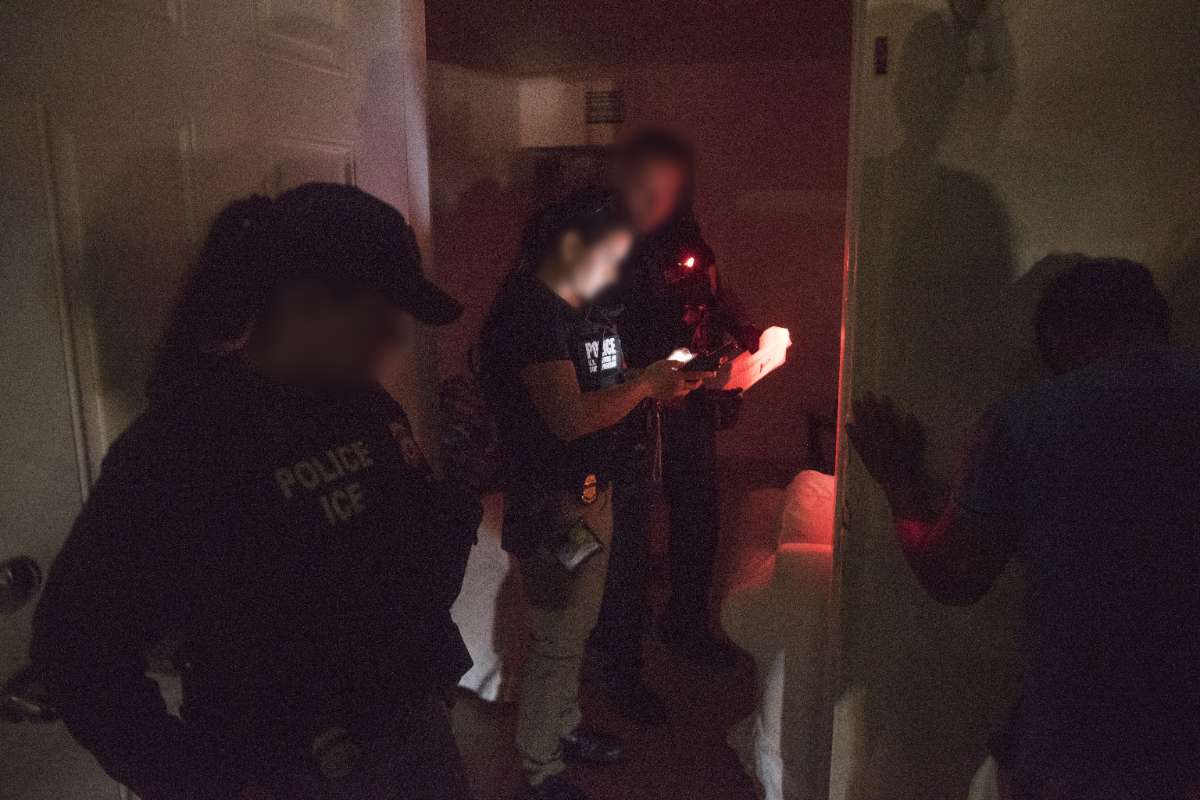

Human Rights Watch has documented at least 33 Uyghurs held in Turkish deportation centers between December 2018 and October 2025, while a Turkey-based nongovernmental group reported over 100 Uyghurs detained in 2024 alone. Several detainees described crowded cells, poor food, and strip-searches, and at least three told Human Rights Watch they were pressured or coerced into signing “voluntary return” forms. One Uyghur interviewed by the group was deported to the United Arab Emirates, a country that has an extradition treaty with China, adding to fears that transfers to third countries could expose people to onward removal.

A central complaint among Uyghur residents is the sudden wave of residency cancellations tied to new administrative decisions. Turkish authorities have been assigning “restriction codes,” including code “G87,” that designate people as “public security threats,” according to lawyers and community members. These restriction codes have cascaded into denials of international protection claims, arbitrary detention, and the initiation of deportation procedures, often without presenting evidence or a clear explanation to those affected. The practical effect has been to strip long-term residents of the legal status they relied on to work, rent homes, and move around freely.

“Until recently, Uyghurs who escaped repression at home felt safe in Türkiye, but as China-Türkiye relations warm, and the Erdoğan government cracks down on refugees and migrants, many are growing fearful,” said Elaine Pearson, Asia director at Human Rights Watch.

Her assessment mirrors what community organizers and defense attorneys are seeing: people pulled into a maze of bureaucratic measures that are hard to challenge, coded labels that are difficult to remove, and an expanding net of police checks that can lead to detention even after release.

Those caught in the system say it is reshaping daily life in harsh ways.

“Now, because I don’t have any legal documents, I cannot even go outside because of fear, even for groceries, because I don’t want to end up in the deportation centre again,” said a Uyghur whose residence permit was cancelled.

Others describe avoiding metro stations or staying off main roads to reduce the chance of identity checks. Community groups report that some parents have stopped sending children to school for weeks at a time to keep a low profile.

Lawyers working on Uyghur cases say the revocations often come without a clear legal basis and are sometimes followed by temporary “humanitarian residence permits” that can be cancelled or not renewed, plunging people back into irregular status.

“There are many cases where the government cancelled the long-term residence permits of Uyghurs and gave them a humanitarian residence permit [instead]. The decision is arbitrary. And some of my clients’ humanitarian residence permits are also cancelled or denied renewal. In such situations, people can be held in those centers for up to one year. Then they will be released without legal status. Then, after a couple of days, another police checkpoint can lead them to detention once again. It is … a horrible vicious cycle for those who don’t have proper documents. Türkiye has increasingly become an unlivable place for Uyghurs,” said a lawyer working on Uyghur cases.

The accounts align with reports of arbitrary detentions that have accelerated since 2024. People flagged with restriction codes say they have had trouble filing or renewing international protection applications, and those with pending appeals have found themselves detained regardless of active cases. Human Rights Watch’s findings include allegations that some detainees, despite asking for legal counsel, were pushed to sign documents in languages they could not read, including forms labeled as “voluntary return.” The mention of a deportation to the United Arab Emirates deepened anxiety, especially among families who fear that a transfer to a third country could serve as a gateway to coercive returns to China.

At the heart of the legal debate is the principle of non-refoulement, a cornerstone of international law that prohibits sending people to countries where they face a real risk of persecution or torture. Rights groups say Turkey’s recent practices toward Uyghurs—detention based on opaque restriction codes, deportations to third countries with extradition pathways to China, and procedural hurdles that hobble protection claims—risk breaching that obligation. Human Rights Watch has urged the authorities to stop all deportations of Uyghurs to third countries and to recognize Uyghurs as refugees on a prima facie basis, meaning recognition would be granted based on their shared risk rather than through lengthy case-by-case assessments.

The use of restriction codes has become a flashpoint because of how quickly it can erase legal safeguards. Code “G87,” cited by attorneys as a frequent marker for Uyghurs, designates individuals as security threats without a court judgment. Once applied, advocates say it often leads to residency cancellations, blocked applications, and detention measures that are hard to contest. People assigned such restriction codes report that administrative reviews are slow, the evidence underpinning decisions is rarely shared, and appeals can drag on while individuals remain in limbo.

In deportation centers, detainees told Human Rights Watch of overcrowded rooms and inadequate food, adding that forced strip-searches were carried out without clear justification. Some reported being moved multiple times between facilities, making it difficult for lawyers and families to track them, and others said they were denied regular access to phones. The duration of detention, up to a year according to the lawyer cited, pushes people toward despair and risky choices, including signing “voluntary” forms simply to avoid prolonged confinement.

For the Uyghur community, which had seen Turkey as a cultural refuge given shared Turkic ties, the change has been striking. For years, the country offered preferential immigration policies and, in some cases, a pathway to citizenship for people of Turkic origin. Families settled, opened small businesses, and joined schools and mosques where Uyghur language and customs were part of daily life. As of November 2025, that sense of security has eroded: rights monitors and community leaders now view Turkey as no longer a safe third country for Uyghurs, warning that more people could fall into an administrative trap where their presence is tolerated one day and criminalized the next.

Officials have not publicly detailed why long-term residents are suddenly losing status en masse, but advocates point to geopolitical and domestic forces moving in tandem. As Ankara pursues closer diplomatic and economic ties with Beijing and tightens migration controls at home, Uyghurs have found themselves caught between international courtship and internal enforcement. The growth of police checkpoints and document checks across major cities has increased the frequency of encounters that end in detention, especially for those whose residence permits were quietly cancelled or replaced with short-term substitutes.

The legal limbo extends beyond detention. People released after months in a deportation center often receive no durable status, according to attorneys and aid groups, leaving them at immediate risk of being detained again at the next checkpoint. Without residency, they cannot lawfully work, sign leases, or access many services. Community organizations say families are running down savings, relying on relatives to cover rent, and skipping medical appointments for fear of identity checks at clinics.

Rights groups are pressing foreign governments to respond as well. Human Rights Watch has called on other countries to halt the transfer of Uyghurs to Turkey and to consider resettling Uyghur refugees already in Turkey who are at risk under the current policies. The appeal seeks to reduce exposure to the residency cancellations and restriction codes that have become common and to provide a path out for those who, even if released from detention, cannot live safely under the present system.

The specific case of a Uyghur deported to the United Arab Emirates has also sharpened concerns about indirect returns. The presence of an extradition treaty with China in that country gives substance to fears that deportations to third states may function as a back door for removals. Lawyers say the risk is not theoretical: once a person is out of Turkey and inside a jurisdiction willing to cooperate with Chinese authorities, options to contest a handover shrink dramatically.

Within Turkey’s bureaucracy, responsibility for residency and removal decisions sits with the migration agency, which administers permits, reviews protection claims, and runs deportation centers. Individuals and lawyers seeking to challenge restriction codes and residency cancellations must file administrative appeals and, in some cases, take cases to court, a process that can stretch for months. Basic information about procedures and rights is available through the Presidency of Migration Management, but Uyghur residents and their legal counsel say the bottleneck is not knowledge of rules; it is the sudden, opaque application of codes and the difficulty of reversing them once applied.

For people living under these rules, the disruption extends to routine tasks. Parents describe staying inside for days, rationing food, and organizing child care around the safest times to step outdoors. Shop owners have shut doors temporarily to avoid movement that could draw attention, while community centers that once hosted cultural classes now focus on emergency legal clinics and translation help for detention proceedings. A single stop at a traffic checkpoint or a random ID inspection in a shopping district can restart the cycle.

Turkey’s policy shift lands at a moment when its broader migration posture has hardened. Over the past two years, authorities have expanded enforcement against irregular migrants and tightened rules on residence permits across several provinces. For Uyghurs, that general clampdown is compounded by the use of restriction codes like G87 and the rising number of residency cancellations. Community spokespeople say the pattern is consistent: long-term residents who once renewed permits without issue are now told they are security risks, denied a clear rationale, and swept into detention with little notice.

Human Rights Watch’s recommendations echo the concerns of lawyers and families navigating the system every day. They argue that halting deportations of Uyghurs to third countries, honoring non-refoulement obligations, and recognizing Uyghur refugees on a prima facie basis would buffer the immediate harms. Without such steps, they warn, the cycle of detention, release without legal status, and re-detention triggered by restriction codes will persist, pulling more people into a process that is difficult to escape.

On the ground, the fear is palpable.

“Until recently, Uyghurs who escaped repression at home felt safe in Türkiye, but as China-Türkiye relations warm, and the Erdoğan government cracks down on refugees and migrants, many are growing fearful,” said Elaine Pearson, repeating the shift that residents describe in their neighborhoods and homes.

The second, quieter refrain comes from those now living out of sight, whose message is more basic: “Now, because I don’t have any legal documents, I cannot even go outside because of fear, even for groceries, because I don’t want to end up in the deportation centre again.”

As rights groups press Ankara to rethink residency cancellations and the automatic use of restriction codes, and as families weigh whether to move again or wait out the policy turn, the choices are narrowing. Advocates say that without prompt changes to stop deportations, unwind opaque coding practices, and restore clear, fair procedures for status, the window that once made Turkey a refuge could close for good.

This Article in a Nutshell

Turkey’s migration policy has shifted, with long-term residency cancellations and restriction codes like G87 used against Uyghurs, triggering arbitrary detention and deportations. Human Rights Watch found at least 33 Uyghurs detained between December 2018 and October 2025, and a Turkish NGO reported over 100 detentions in 2024. Detainees describe poor conditions and coercion to sign “voluntary return” forms; one was deported to the UAE. Rights groups warn these measures risk violating non-refoulement and call for halting deportations and recognizing Uyghurs as refugees prima facie.