(SOMALIA) — temporary protected status (TPS) is often the first—and sometimes the strongest—defense against removal for somali nationals who have relied on it for years, but a new Department of Homeland Security (DHS) announcement ending Somalia’s designation has put many recipients on a fast clock toward potential deportation.

1) Overview: TPS termination for Somalia and key facts

TPS is a humanitarian protection created by congress that allows eligible nationals of certain countries to remain in the United States temporarily when conditions at home make return unsafe or impracticable.

When a person is granted TPS, they are generally considered to be in a period of authorized stay. they may also obtain employment authorization tied to TPS, and some TPS holders receive permission to travel abroad with prior authorization.

A “termination” announcement does not usually mean immediate arrests the next day. It typically means DHS has set an effective date on which TPS-based protection ends, and after that date work authorization linked to TPS ends as well.

People who have no other lawful status can become removable and may be placed in removal proceedings. The practical stakes are significant: a TPS termination can affect U.S.-citizen children, spouses, employers, caregivers, state driver’s license eligibility, and access to certain state benefits (which vary by state).

Readers should plan early. The key dates include the announcement date, a Federal Register notice date, and a future effective date when TPS-related work authorization expires. Those date details are best viewed together, because planning depends on them.

The headline point is that the remaining window is short.

Deadline Watch: If your work permit is based on Somalia TPS, confirm the expiration date on your EAD and any automatic extension rules in the Federal Register notice. Do not assume your employer “already knows.”

2) Legal framework and rationale

TPS is governed primarily by INA § 244. DHS may designate a country for TPS when statutory conditions exist, including: (1) ongoing armed conflict, (2) environmental disaster, or (3) “extraordinary and temporary conditions” that prevent safe return. See INA § 244(b).

The same statute also permits DHS to extend or terminate a designation. DHS generally frames terminations around a finding that the conditions supporting designation have sufficiently improved, often stating that continuing TPS would be inconsistent with the statutory “temporary” nature of the program.

Procedurally, termination usually occurs through publication of a notice in the Federal Register. The notice sets an effective date and explains any re-registration or wind-down mechanics. In some prior TPS disputes, litigation has delayed terminations through injunctions, but injunctions are not automatic and courts vary in their approach.

In practice, affected TPS holders should treat the termination as real unless a court order or a new DHS announcement changes the effective date. Monitoring USCIS and the Federal Register matters because small wording changes can affect work authorization and filing options.

3) Demographic and geographic impact

Although only a subset of Somali nationals in the United States hold TPS, the community impact can be broader. Many Somali Americans are U.S. citizens or lawful permanent residents and are not directly affected; others may be in different statuses, including asylum, student status, or family-based processes.

Minnesota is frequently cited as the state with the largest Somali population, concentrated in the Minneapolis–St. Paul area. Geographic concentration can improve access to specialized immigration counsel and community organizations, but it can also increase visibility of enforcement operations and the speed at which information—and misinformation—spreads.

Employers in health care, logistics, hospitality, and caregiving may feel disruptions when work authorization ends. Families may face housing and schooling instability if a primary wage earner loses lawful work authorization.

A key sensitivity point: nationality or community membership does not determine immigration status. Community members should avoid assumptions about neighbors, employees, or congregants.

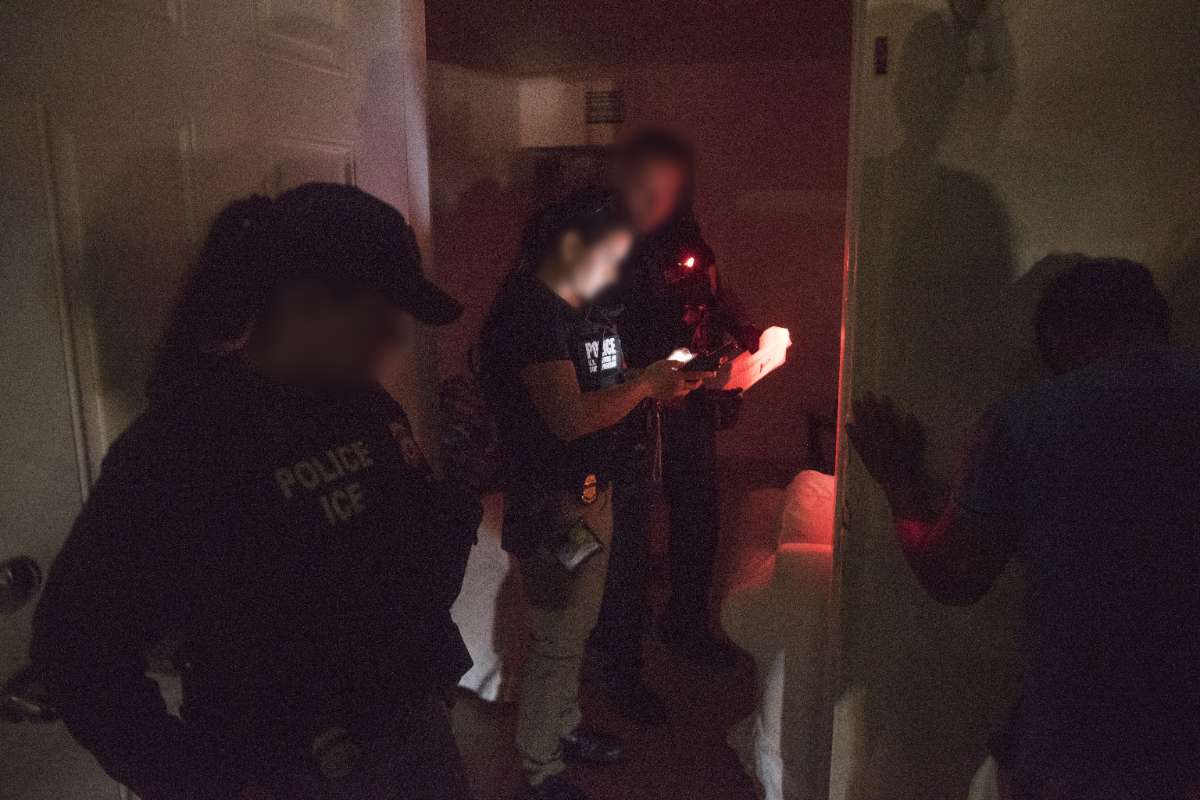

4) Enforcement actions and immediate consequences

Once TPS ends, the main legal change is the loss of TPS-based protection from removal and TPS-based work authorization, unless the person holds another lawful status or independent protection. Some individuals may have a pending application that provides a separate basis to remain; others may not.

Enforcement risk is not uniform. Factors that can increase risk include a prior removal order (including an in absentia order), past missed immigration court hearings, criminal arrests or convictions, prior fraud findings, and existing ICE reporting requirements.

- A prior removal order.

- Missed immigration court hearings.

- Criminal arrests or convictions.

- Prior fraud findings.

- Existing ICE reporting requirements.

DHS statements urging “self-departure” and warning of arrests generally signal increased enforcement intent, though outcomes depend on local priorities, available resources, and individual case histories.

Immediate planning steps often include employment planning and family contingency planning. Employers may need to reverify work authorization when an EAD expires, and state driver’s licenses and other state benefits can change if lawful presence ends; rules vary by state.

Warning: If you have a prior order of removal, do not wait for the TPS end date. You may need a motion to reopen or other court strategy, and those take time.

5) Reactions, policy responses, and legal challenges

The administration’s public rationale for ending Somalia TPS centers on claimed improvements in country conditions and the statutory requirement that TPS be temporary. Public debate has been shaped by enforcement actions and local political responses, particularly in Minnesota.

State and city leaders sometimes respond with litigation aimed at limiting aspects of federal enforcement operations. These cases can challenge cooperation agreements, policing practices, or constitutional violations, but they typically cannot grant lawful immigration status to individuals or guarantee a nationwide pause of removals.

The practical takeaway: litigation may change timing, but it is not a plan by itself. TPS holders should not assume an automatic court-ordered pause. If a court later issues an injunction, that can create options; until then, deadlines still matter.

6) Potential avenues for affected individuals (defense strategy)

When TPS ends, the strongest defense strategy is usually a rapid, attorney-led screening for other relief. Several options may exist, but each has strict requirements and procedural traps.

Asylum, withholding, and CAT

Asylum is authorized by INA § 208 and generally requires proving past persecution or a well-founded fear of future persecution on account of a protected ground. The one-year filing deadline often applies, though exceptions may exist.

Withholding of removal under INA § 241(b)(3) has a higher standard but no one-year deadline. Protection under the Convention Against Torture (CAT) is possible where torture by, or with acquiescence of, a public official is more likely than not.

Asylum cases are fact-intensive and depend on personal history, corroboration, credibility, and current country conditions.

Cancellation of removal

For people placed in immigration court, cancellation of removal may be a key defense. Lawful permanent residents and nonpermanent residents have different requirements under INA § 240A.

For nonpermanent residents, the standard commonly involves long continuous presence, good moral character, and “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship” to a qualifying U.S.-citizen or permanent resident relative. The stop-time rule and criminal bars can be decisive.

Adjustment of status and other pathways

Some TPS holders may have a family-based or employment-based route. Eligibility often turns on whether the person was “inspected and admitted or paroled”, whether any unlawful presence bars apply, and whether waivers are available.

Consular processing may be possible for some, but travel and reentry risks must be assessed carefully. TPS also intersects with travel and parole rules; advance travel without proper authorization can create severe consequences.

Anyone considering travel should consult counsel first and confirm current USCIS policy and documentation.

Evidence typically needed

Successful cases are built on documentation. Attorneys typically look for identity documents, proof of TPS registration history, employment and tax records, immigration notices, and criminal dispositions if any.

They also seek family relationship evidence, medical and school records for hardship, and country conditions materials. The goal is to match documents to each element of a potential form of relief.

Document Warning: Get certified court dispositions for any arrest—dismissed or not. Immigration consequences often turn on the exact statute of conviction.

Just as important is choosing qualified help. Notarios and unlicensed consultants can cause irreversible harm. Look for a licensed immigration attorney or a DOJ-accredited representative, confirm credentials, and get written fee agreements.

7) Historical context and prior TPS actions

Somalia’s TPS designation has been long-running, with multiple extensions and redesignations across administrations. That history has created understandable reliance interests for families and employers, but legally long duration does not guarantee permanence.

TPS is not a direct path to a green card, and Congress has not enacted a universal adjustment program for long-term TPS holders. Administrations differ in how they evaluate country conditions and national interest factors, producing policy volatility.

Past cycles of redesignation and extension can also shape evidentiary records, because many TPS holders have extensive, well-documented U.S. residence that may support other relief depending on eligibility.

8) What to watch next and data sources

Three developments can change the real-world impact quickly: (1) a court injunction delaying termination, (2) a revised Federal Register notice adjusting effective dates or work authorization, or (3) a new DHS designation or redesignation decision.

For reliable updates, monitor USCIS TPS pages and alerts, the Federal Register, and EOIR court information if you are in proceedings. If you have a pending case, track every deadline and keep proof of filing.

Policy can move quickly. Treat any timeline as current only as of publication date: Tuesday, January 13, 2026.

Official sources (U.S. government):

⚖️ Legal Disclaimer: This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.

Resources:

The U.S. government is ending Temporary Protected Status for Somalia, placing thousands at risk of deportation. This change eliminates work permits and legal protection from removal. Somali communities, particularly in Minnesota, must now navigate complex legal challenges. Success requires immediate screening for alternative relief, such as asylum or family-based adjustment, before the effective termination date to avoid severe enforcement consequences and family instability.