(BALTIMORE) Kilmar Abrego Garcia was taken into ICE custody on the morning of August 25, 2025, during a scheduled check-in at the Baltimore field office, according to his attorney and multiple news outlets. The move came three days after his release from federal criminal detention and set off fresh legal action over where the government can send him next.

ICE has told his lawyers it intends to deport him to Uganda under a new transfer arrangement, even though a federal court barred his removal to El Salvador in 2019 after finding he had a credible fear of persecution there. His case has become a test of how far the government can go with third-country deportations and how courts will balance criminal charges with long-standing protection claims.

Background and recent history

Abrego Garcia, a native of El Salvador, was mistakenly deported there in March 2025 despite that 2019 court order. He was held in a Salvadoran prison for months, his family and supporters say, until a federal court—backed by the Supreme Court—ordered his return to the United States in June 2025.

That forced return became a flashpoint in immigration circles, raising doubts about safeguards meant to prevent removal when a judge has barred it.

- For supporters, the mistake highlighted the system’s gaps.

- For immigration officials, the case has been framed as a complex mix of past protection rulings and present-day enforcement priorities.

Upon his return, federal agents jailed him on human smuggling charges tied to a 2022 incident in Tennessee. A judge approved his release from pre-trial detention on Friday, August 22, 2025, with conditions that he remain in Maryland under electronic monitoring and ICE supervision while awaiting trial in January 2026.

His criminal case is separate from removal proceedings, yet the two timelines now intersect with unusual force: if ICE removes him before trial, the criminal case could stall; if the court stops the removal, ICE could be forced to keep monitoring him while both the criminal case and immigration issues unfold side by side.

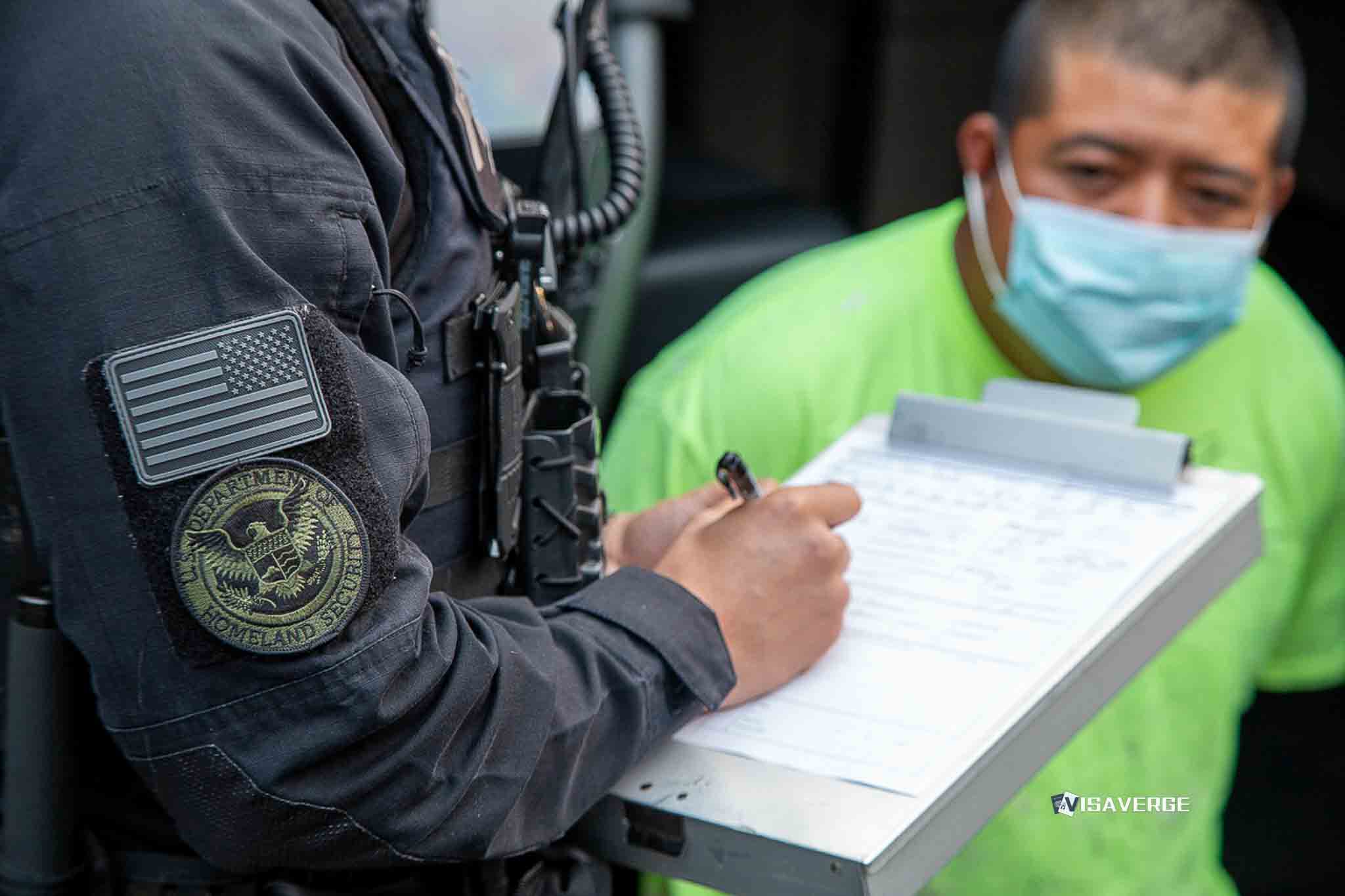

ICE notice and third-country transfer plans

In the days leading up to the check-in, ICE provided formal notice through its Office of the Principal Legal Adviser that it could remove him to Uganda no earlier than 72 hours after the notice, excluding weekends.

- Based on the letter’s timing, removal could be attempted as early as August 28, 2025, if no court steps in.

- ICE cites a new agreement with Uganda to accept deported migrants when return to a person’s home country is blocked.

Lawyers for Abrego Garcia argue that transferring him to a third country without a judge’s full review of the risks there violates his rights. They also note that the government previously misapplied the order barring removal to El Salvador, which they say should trigger stricter oversight now.

“A court must examine the risks he faces there before any transfer,” lawyers are expected to argue in emergency filings.

Public reaction and local officials

The day of his arrest at the Baltimore field office, a crowd gathered before sunrise outside the building. Faith leaders, immigrant advocates, and neighbors held a vigil for hours—holding signs and praying for a halt to the removal plan.

Inside, lawyers pressed ICE to delay any transfer until a court could hear new filings. Outside, families whispered worries about their own check-ins—routine visits that can end with a return home or with a ride to a detention center.

Maryland officials have stepped in as the case reached this stage:

- Sen. Chris Van Hollen has called for judicial review, calling the administration’s drive to deport a “malicious abuse of power” and promising to keep fighting for due process.

- Gov. Wes Moore has urged that a judge, not the executive branch, decide the outcome.

Their remarks reflect wider unease about fast-tracking removals when old protection orders and new criminal charges collide.

Government stance and outside commentary

ICE and Department of Homeland Security officials maintain that Abrego Garcia is subject to removal based on alleged gang affiliation—an allegation his family denies—and his federal charges.

- The agency says it is following the law, including the process for third-country deportations when returns to a person’s home country are blocked.

- On August 24, 2025, Tom Homan, a senior border official under the Trump administration, said deportation to Uganda was imminent and defended the government’s approach as lawful and necessary.

Timeline and legal posture

- 2019: Federal court order bars removal of Abrego Garcia to El Salvador due to credible fear of persecution.

- March 2025: Mistaken deportation to El Salvador; held in a Salvadoran prison for several months.

- June 2025: Returned to the United States under federal court and Supreme Court orders.

- August 22, 2025: Released from pre-trial federal detention under electronic monitoring and ICE supervision; trial set for January 2026.

- August 25, 2025: Detained again by ICE at a scheduled check-in at the Baltimore field office.

- Formal notice: ICE may remove him to Uganda no earlier than 72 hours after notice issuance, excluding weekends; earliest timing falls on August 28, 2025, absent a court stay.

Lawyers for Abrego Garcia are expected to seek emergency relief to block removal to Uganda, arguing that a court must examine the risks he faces there before any transfer. Their position draws on two policy threads:

- ICE’s wider use of expedited removal in recent years has increased the speed at which people are processed if they cannot show continuous two-year presence.

- When return to a person’s home country is barred, ICE can ask a third country to accept the person.

Advocates say that combination can undercut due process if judges don’t fully review safety concerns and legal claims tied to a third country.

Maryland’s top officials are echoing the call for a court-centered process. Van Hollen and Moore have publicly pressed for judicial oversight, saying the executive branch should not decide his fate alone. Their stance has energized local supporters and drawn national attention to the legal questions at stake:

- How courts should weigh a past protection order to avoid El Salvador

- Whether expedited removal can reach a third country

- What standards apply when a person must appear in federal criminal court while ICE seeks to deport him elsewhere

Broader enforcement context

The case is landing at a time of intense enforcement.

- As of July 2025, the average length of ICE detention had risen to about 50 days, with many people held for months while fighting removal in immigration court.

- Detention numbers are near record highs, reflecting stepped-up arrests, transfers from criminal custody, and tighter supervision rules.

Advocacy groups and legal scholars say detention often feels punitive, especially for people with pending protection claims, medical needs, or long ties to their communities. Officials counter that detention is a tool to ensure court appearances and remove those with final orders.

Third-country deportations remain rare but are growing. ICE says they are a lawful way to carry out removal orders when a person cannot be returned home, such as when a judge bars removal to that country.

- Legal experts warn these transfers can raise human rights concerns if the new country isn’t fully assessed for safety risks tied to the person’s background, family, or past persecution.

- The debate is sharpest when the person has already faced harm—as in Abrego Garcia’s months in a Salvadoran prison—and when mistakes, like his March removal despite a 2019 bar, have already occurred.

According to analysis by VisaVerge.com, these kinds of transfers also test the limits of judicial oversight and the balance of power between courts and the executive branch.

What families and advocates can do now

For families and attorneys seeking updates, ICE directs the public to the Online Detainee Locator System to confirm custody and location changes. The tool can be accessed at https://locator.ice.gov.

Advocates advise checking often when removal is imminent, because transfers between facilities or to airports can happen quickly once the 72-hour window closes. Supporters in Baltimore said they planned to monitor the system throughout the week, fearing a sudden move if no court order blocks removal.

At the Baltimore vigil, organizers emphasized the fear that routine check-ins can produce—especially when a person’s status rests on a past court order and a pending criminal case. The group urged officials to let a judge decide whether Uganda is safe for him and whether removal should wait until after the January 2026 trial. Faith leaders framed the situation as a matter of fairness and warned that fast removals can break families apart without proper review.

Stakes and possible outcomes

Inside government, officials cast the case as part of a broader strategy to enforce the law while managing complex individual histories. They stress that:

- The criminal charges—human smuggling tied to a 2022 event—are serious.

- Supervision conditions were set by a federal court.

- Third-country removals follow established legal pathways when a person cannot be returned to a barred country like El Salvador.

The clash between those positions and the community’s demands for a full court review is playing out hour by hour.

Possible next steps:

- A court issues a stay before August 28, 2025:

- ICE would be blocked from removing him to Uganda until the court reviews the risks and legal claims tied to the third-country transfer.

- No stay is issued:

- ICE may proceed under the notice it has already issued, and removal could occur once the 72-hour window (excluding weekends) closes.

For advocates, the outcome could set a model for future third-country cases. For ICE, it could affirm its authority to use new agreements to carry out removals when home-country returns are not allowed.

What is certain is that thousands of immigrants and their families are watching this case—from Baltimore to other cities where check-ins can change lives in an instant. In that sense, the story of a man from El Salvador meeting with officials at the Baltimore field office—and then walking into ICE custody—captures a much larger moment in American immigration enforcement, where past court orders, new deportation tools, and community pressure all collide in the same hallway.

This Article in a Nutshell

ICE detained Kilmar Abrego Garcia in Baltimore on August 25, 2025, after his June return from a mistaken March deportation to El Salvador. ICE plans to remove him to Uganda under a new agreement, but lawyers seek emergency court review to block transfer, citing a 2019 order barring removal to El Salvador and risks tied to third-country deportations.