A late-December 2025 federal court ruling has cleared the way for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to share limited “basic personal information” from Medicaid enrollment files with U.S. Immigration & Customs Enforcement (ICE), while barring the disclosure of medical histories and clinical records. Practically, the decision may make it easier for ICE to locate noncitizens in removal proceedings and to initiate new deportation cases using addresses and identifiers already contained in benefits files—without turning Medicaid into an open medical-records portal.

The policy is scheduled to take full effect January 6, 2026, after a temporary block expired. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has described the ruling as enabling enforcement aimed at restricting Medicaid to eligible beneficiaries. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has defended the agreement as lawful and compliant with applicable privacy rules.

Although this is not a Board of Immigration Appeals precedent, it is best read as a front-end enforcement development that will influence what shows up in immigration court: how DHS finds respondents, what evidence appears in the record, and which suppression and due-process arguments are likely to be litigated.

Important note on citations: There is no published BIA precedent squarely addressing “Medicaid data sharing with ICE” as of today. Longstanding BIA rules on evidence and suppression, however, will shape how this data is used in immigration court. Two key precedents are Matter of Barcenas, 19 I&N Dec. 609 (BIA 1988) and Matter of Puc-Ruiz, 23 I&N Dec. 814 (BIA 2005).

What the court allowed—and what it did not

According to official descriptions of the policy and the court’s order summarized in public reporting, CMS may share certain Medicaid data elements with ICE, including:

- Citizenship/immigration-status indicators

- Home address and phone number

- Date of birth

- Medicaid ID

The order reportedly prohibits disclosure of sensitive medical histories and health records, and it excludes U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents from the data-sharing scope.

This distinction matters in later deportation cases. A home address can support a targeted arrest or service attempt. But an address, standing alone, does not prove alienage, deportability, or removability. DHS still must establish removability by “clear and convincing evidence” in most removal proceedings. See INA § 240(c)(3).

Key facts leading to the decision

The dispute arose from a federal initiative allowing CMS to share limited Medicaid enrollment information with DHS for immigration enforcement. A coalition of states and advocates challenged the arrangement.

The challengers argued, among other things, that the information exchange violated:

- privacy protections, and

- federal administrative law requirements, including the Administrative Procedure Act (APA).

A U.S. district judge reportedly drew a line between identity/location data and medical-record content, permitting the former while restricting the latter. The injunction that previously blocked the practice did not continue, opening the door to implementation the next day.

From an immigration-law perspective, the most consequential fact is not the precise dataset. It is the institutional handoff: benefits administration data becoming a routine lead source for ICE operational databases and field actions.

Warning (healthcare and immigration intersection): Even where disclosure is limited, fear of information sharing can deter eligible family members from seeking care. That can create downstream immigration problems. Missed care can affect disability documentation, hardship evidence, and case preparation.

How this changes the playbook in deportation cases

The ruling may affect removal cases in at least four ways.

1) More “locate” leads, fewer dead files

ICE frequently faces practical barriers in executing arrest operations or serving paperwork when addresses are outdated. Medicaid enrollment files tend to contain recent addresses and phone numbers, which may make enforcement actions more efficient.

- In court, that can mean more respondents actually appear in proceedings because they were found.

- It can also mean more in-custody arrests. Custody status often affects case strategy, bond eligibility, and timelines.

2) More litigation over how DHS obtained identity evidence

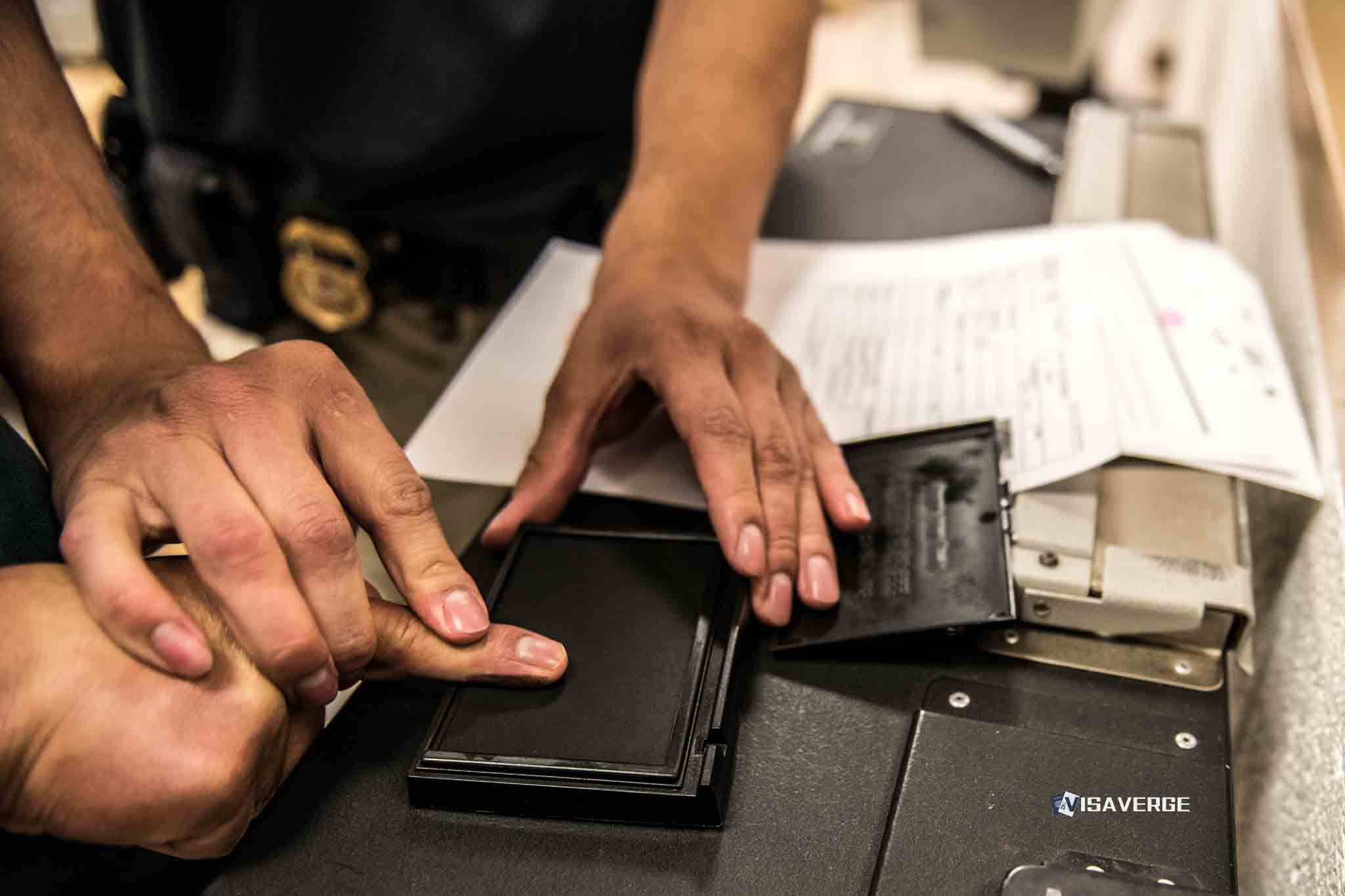

Immigration court evidentiary rules are broad. DHS often introduces biographic data through Form I-213 and related records. Yet respondents can challenge unlawfully obtained evidence in limited circumstances.

The core BIA framework is:

- The respondent must make a prima facie showing that evidence was unlawfully obtained. Matter of Barcenas, 19 I&N Dec. 609 (BIA 1988).

- Suppression is generally reserved for egregious constitutional violations or conduct that undermines reliability. See Matter of Puc-Ruiz, 23 I&N Dec. 814 (BIA 2005).

Whether Medicaid data acquisition qualifies as unlawful, or egregious, will depend on the final program terms, implementation details, and the court order’s limits. Expect motions seeking discovery or subpoenas focused on:

- what exactly ICE received, and

- how it was used.

3) Service and notice fights may intensify

If ICE uses Medicaid data to find a person, DHS may also rely on those addresses for service. That could reduce some nonappearance cases, but it could also create disputes if a file contains an address the person never controlled.

Noncitizens ordered removed in absentia sometimes seek reopening based on lack of notice. See INA § 240(b)(5)(C). Future motions may turn on whether DHS used an address from Medicaid enrollment and whether it was reliable.

Deadline callout (in absentia orders): A motion to reopen for lack of notice under INA § 240(b)(5)(C)(ii) has different timing rules than other reopenings. If you miss a court date, get legal help immediately.

4) Public-benefits evidence may appear in discretionary decisions

Even when the dataset is limited, the existence of Medicaid enrollment could surface in discretionary contexts. For example:

- Some forms of relief require weighing equities, hardship, and credibility.

- Where benefits use is lawful (e.g., emergency Medicaid or coverage for eligible children), it should not be treated as misconduct.

- Attorneys should anticipate possible mischaracterizations and prepare clean documentation.

This also intersects with USCIS SAVE (status verification) verification processes, which states and agencies use to verify immigration status for benefits. SAVE itself is not “ICE,” but it is part of the broader status-verification ecosystem. For readers, the takeaway is that benefits systems and immigration systems increasingly communicate through formal and informal channels.

What does the INA say about the government’s burden?

Even with stronger locating tools, DHS still must prove removability.

- In removal proceedings, DHS generally bears the burden to show alienage and removability by clear and convincing evidence. INA § 240(c)(3)(A).

- After alienage is established, the burden may shift for certain relief applications. See INA § 240(c)(4).

Medicaid data may help ICE find someone and may suggest identity. But it typically will not, by itself, establish the legal elements of removability. DHS still commonly relies on immigration records, admissions, prior orders, or border encounter documentation.

Circuit splits and conflicting authority to watch

Because the immediate ruling is from a federal district court, it does not automatically bind other districts. Additional lawsuits may proceed in other jurisdictions, potentially creating inconsistent injunctions or appellate rulings.

Separately, suppression standards in immigration court have long varied across circuits, especially on:

- what counts as “egregious”, and

- when exclusion is warranted.

The BIA’s baseline approach is restrictive, but some circuits apply more protective interpretations in particular contexts. Noncitizens should consult counsel about the law in the circuit where their immigration court sits.

Warning (jurisdiction matters): Immigration court location can affect strategy. Suppression, reopening, and due-process arguments can play differently by circuit.

Practical takeaways for noncitizens and mixed-status families

- Assume “basic personal information” can travel. If you are enrolled in a public program, treat your address and phone number as potentially shareable under some authorities.

- Do not lie on benefits applications. A false claim to U.S. citizenship can carry severe immigration consequences and can be a permanent bar in many cases. See INA § 212(a)(6)(C)(ii).

- Keep copies and update addresses consistently. In removal proceedings, address updates must be filed with the immigration court and DHS. Missed notices can lead to in absentia orders. See INA § 239(a)(1)(F).

- If ICE contacts you, get individualized legal advice fast. Whether to speak, sign, or provide documents depends on facts, posture, and any pending relief.

Deadline callout (address changes): In immigration court, failing to update your address can have serious notice consequences. Speak with counsel about EOIR and DHS change-of-address requirements immediately after any move.

Where this leaves practitioners

For attorneys, the key near-term questions are evidentiary and procedural:

- Can respondents obtain discovery on the data transfer and its scope?

- Does the record show use beyond the court’s limits, such as medical-record content?

- Are there APA-based remedies that indirectly affect removal cases, such as program suspension?

- How should counsel develop a record for suppression or termination motions where appropriate?

Because this issue blends healthcare administration, privacy statutes, and immigration enforcement, it is not a standard one-motion practice area. It is a cross-disciplinary fight that may require coordinated federal litigation awareness and careful motion practice in EOIR.

Quick reference table: Allowed vs. Prohibited data elements (as summarized in public reporting)

| Allowed (reported) | Prohibited (reported) |

|---|---|

| Citizenship/immigration-status indicators | Sensitive medical histories |

| Home address and phone number | Clinical records |

| Date of birth | — |

| Medicaid ID | — |

| Excludes U.S. citizens & LPRs | — |

Official resources

- EOIR Immigration Court information: U.S. Department of Justice EOIR

- USCIS SAVE (status verification): USCIS SAVE

Resources:

– AILA Lawyer Referral

Legal Disclaimer: This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.

Starting January 6, 2026, ICE can access basic Medicaid enrollment data, such as addresses and birth dates, to aid in locating noncitizens for deportation. However, the court has explicitly forbidden the transfer of clinical or medical records. This policy shift increases the likelihood of arrests and heightens the need for aggressive legal defense regarding how biographic evidence is obtained and used in immigration court proceedings.