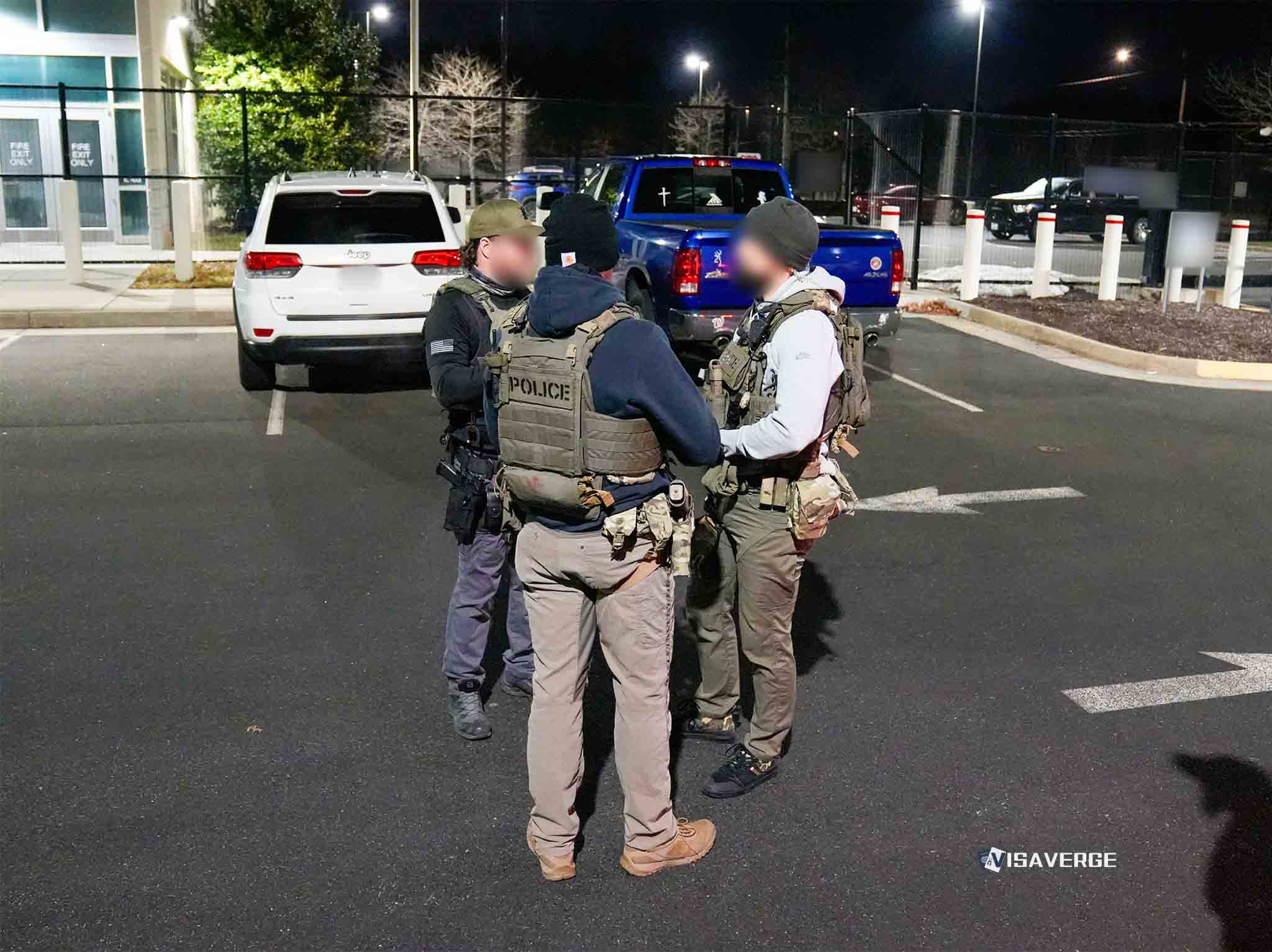

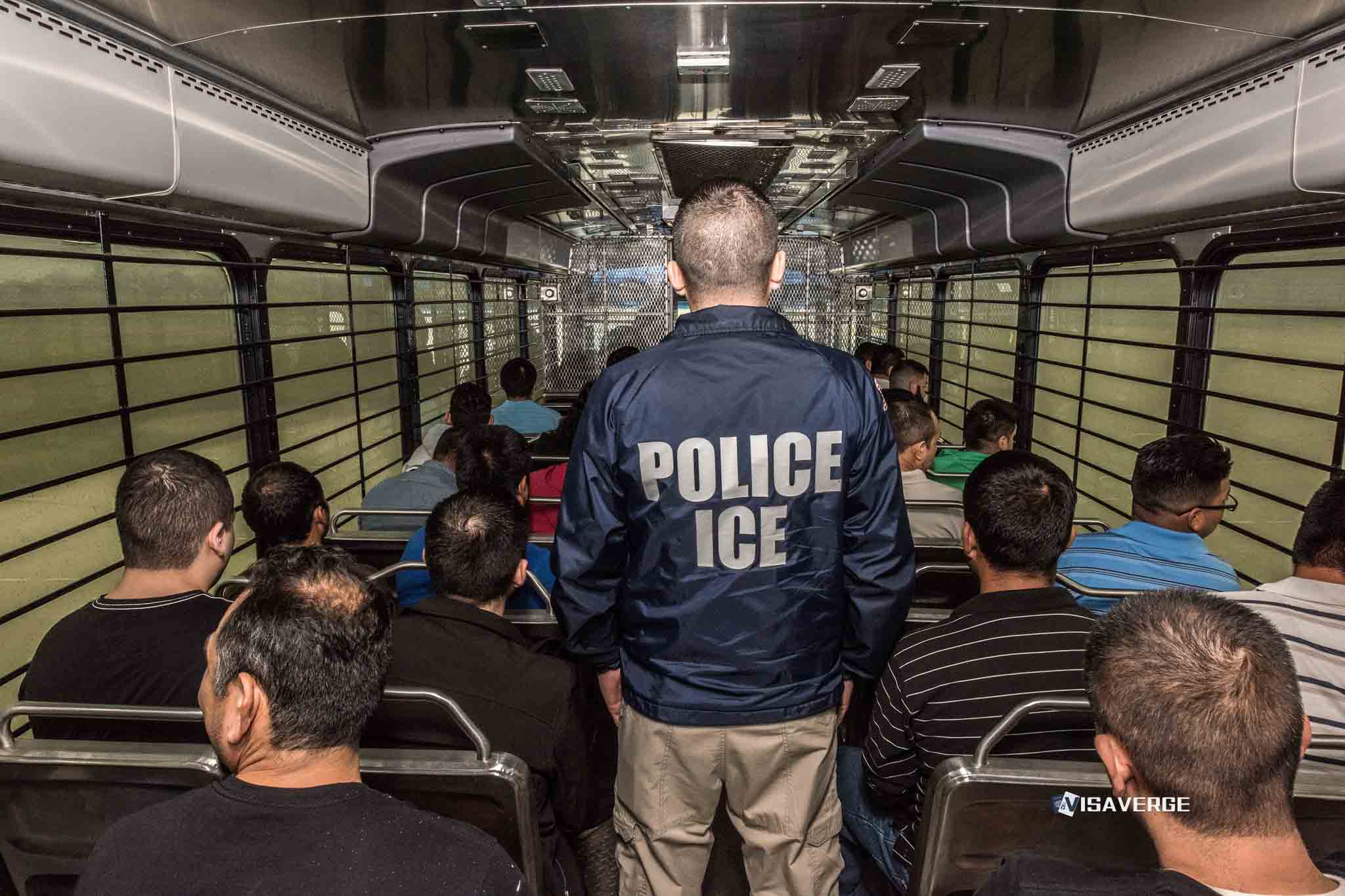

(FREMONT, CALIFORNIA) Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents carried out what the agency calls “Knock and Talk” visits in the Sundale neighborhood of Fremont over the weekend, prompting sharp concern from community leaders who say the activity frightened families and disrupted daily life.

The early Saturday morning contacts took place in a diverse area known for welcoming many Afghan refugees. Advocates say the timing, the approach to private homes, and the absence of local police fueled alarm among residents who already feel on edge about immigration enforcement.

What ICE says the visits were

ICE described the visits as voluntary conversations. Under the “Knock and Talk” approach, agents go to a residence, knock on the door, and ask to speak with people inside. The agency did not present warrants in these encounters, according to community leaders who spoke with residents afterward.

This detail is central to the dispute: while ICE frames the visits as consensual and low-key, neighbors reported anxiety, confusion, and the sense that they were being singled out.

- Parents said children were too scared to attend school.

- Others hesitated to seek medical care and public services in the days that followed.

Community reaction and concerns

Community organizers who monitor Fremont said the focus on Sundale, a hub for new arrivals from Afghanistan, left many residents feeling they were targeted based on background rather than any specific case.

Several local advocates characterized the activity as “terrorizing”, arguing that the presence of federal officers at front doors, especially early on a Saturday morning, chilled ordinary routines. They reported:

- Some families did not open their doors, unsure of their rights.

- Others felt pressured to answer questions despite the “voluntary” label.

The visits reportedly took place without local police present, a point that alarmed neighborhood leaders who often coordinate with city officials during tense moments. They worry the lack of coordination could undercut trust built over years between public agencies and immigrant households.

When asked why agents appeared at certain addresses, residents said they received no clear explanation — which they saw as reinforcing the risk of racial profiling.

Legal context and rights guidance

According to analysis by VisaVerge.com, “Knock and Talk” operations are commonly described by ICE as voluntary, non-custodial contacts, and agents do not have authority to enter a home without consent or a judicial warrant.

That distinction matters in communities like Sundale, where many people have fled violence, endured long refugee screenings, and now try to settle into schools and jobs. For families who have started over after difficult journeys, a knock from federal officers can bring back fear of sudden upheaval.

Local mentors and caseworkers said they handled multiple calls from clients asking whether they should keep children home and whether it was safe to go to routine doctor’s appointments.

Practical rights reminders shared by volunteers and legal aid

- Immigration officers may speak at the door but cannot enter a residence without consent or a judicial warrant.

- Residents can ask officers to slide any documents under the door and to check whether a warrant is a judicial warrant bearing a judge’s signature.

- Individuals may choose not to engage with officers at the door.

Civil society volunteers urged calm but acknowledged that the encounters, by nature, can feel intimidating even when no arrests are made.

How the visits unfolded for residents

Residents who were home during the visits described short interactions through doorways or peepholes.

- Some were told agents wanted to “ask a few questions.”

- Others reported hearing their names or the names of people they did not recognize.

- With no warrant shown, several households declined to open their doors.

Volunteers advised neighbors about rights and steps to verify officers’ identities, but they also noted how traumatic such contacts can be given many residents’ backgrounds.

City response and coordination concerns

City officials were pressed to explain what they knew. Community leaders said they did not see Fremont police accompanying ICE and questioned whether the city was notified in advance.

The absence of local officers removed a familiar bridge for residents who often rely on city channels for quick answers. Advocates said this gap made it harder to verify:

- How many homes were contacted

- Whether agents were looking for a particular person

- Or if they were simply trying to gather general data

Without those details, rumors spread quickly in neighborhood WhatsApp groups and quieted grocery store aisles and parks that would normally be busy on a weekend.

Impact on schools, health care, and daily life

Neighborhood mentors who track attendance reported an immediate effect on schools. Families kept children home on Monday out of fear agents would return or visit bus stops. Health workers who support Afghan newcomers also reported missed appointments.

The chilling effect is a familiar pattern, they said, when immigration enforcement touches a tight-knit area. Even though ICE emphasized “Knock and Talk” as voluntary, the community heard a different message at the door — one colored by past trauma and the fear that cooperation could lead to future problems.

Legal aid and community support

Legal aid providers said they were preparing to offer briefings and hotlines to answer questions about door-knock encounters. While no arrests were reported by local advocates after the Sundale activity, they argued that the damage was already done:

- Trust in government took a hit

- Routine services suffered

They urged federal officials to coordinate with local authorities and to consider the timing and manner of neighborhood contacts in places with large refugee populations.

ICE public information and local requests

ICE maintains that community engagement is part of its mission. The agency’s Enforcement and Removal Operations division outlines objectives and operational roles on its website, which explains how officers identify, arrest, and process people who fall within federal priorities. For reference, the agency provides public information through ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations.

Fremont leaders said that if “Knock and Talk” continues, they want:

- Clear, advance communication that respects residents’ rights

- Steps to avoid the appearance of racial profiling

Community responses and next steps

Neighbors in Sundale say they hope for swift outreach to repair trust.

- Several faith leaders plan to meet with families to answer questions and share rights information.

- Youth coaches and teachers want to reassure students that school remains a safe place to learn and that counselors are available if anxiety persists.

- Community groups will track whether similar visits happen elsewhere in Fremont and whether patterns emerge that suggest unequal treatment of certain ethnic groups.

For now, the door-knock debate shows no sign of fading. Residents repeat the central tension: ICE refers to “Knock and Talk” as a voluntary conversation; neighbors see federal badges at their door before sunrise.

In a city where many escaped war and uncertainty, that contrast is not an abstract policy issue — it lands in living rooms, hallways, and children’s bedrooms. Fremont’s leaders say they want to prevent that fear from spreading and to keep families engaged with schools, clinics, and jobs.

Whether future encounters look different may depend on how ICE balances its stated goals with the lived reality of those on the other side of the door.

This Article in a Nutshell

ICE conducted early Saturday “Knock and Talk” visits in Fremont’s Sundale, described as voluntary by the agency. Visits reportedly lacked warrants and local police accompaniment, alarming residents—many Afghan refugees—who reported children missing school and reduced use of health services. Community leaders accused ICE of creating a climate of fear and possible racial profiling. Legal aid groups offered rights briefings; advocates urged clearer advance communication and coordination with local authorities to restore trust and protect access to services.