(UNITED STATES) The number of Colombians deported from the United States has hit the highest level in almost three decades, with 23,045 people sent back in the first six months of 2025. That already exceeds the total for all of 2024 and tracks the pace last seen in the late 1990s, according to U.S. enforcement tallies reviewed by VisaVerge.com. The rise follows an aggressive shift in immigration policy under President Trump after his return to office on January 20, 2025, and marks a broader expansion of arrests, detention, and rapid removals across the border and interior.

Since inauguration day, an average of 140 Colombians deported daily has become the new normal. Colombia is now the fifth most affected nationality, after Mexico (77,925), Honduras (53,604), Guatemala (51,886), and Venezuela (26,578). Across all countries, total U.S. deportations reached 344,096 by June 2025, surpassing the previous fiscal year’s 316,216. For Colombian families who had hoped for stability after years of rising migration, the change has been sudden and painful.

Enforcement surge and policy resets

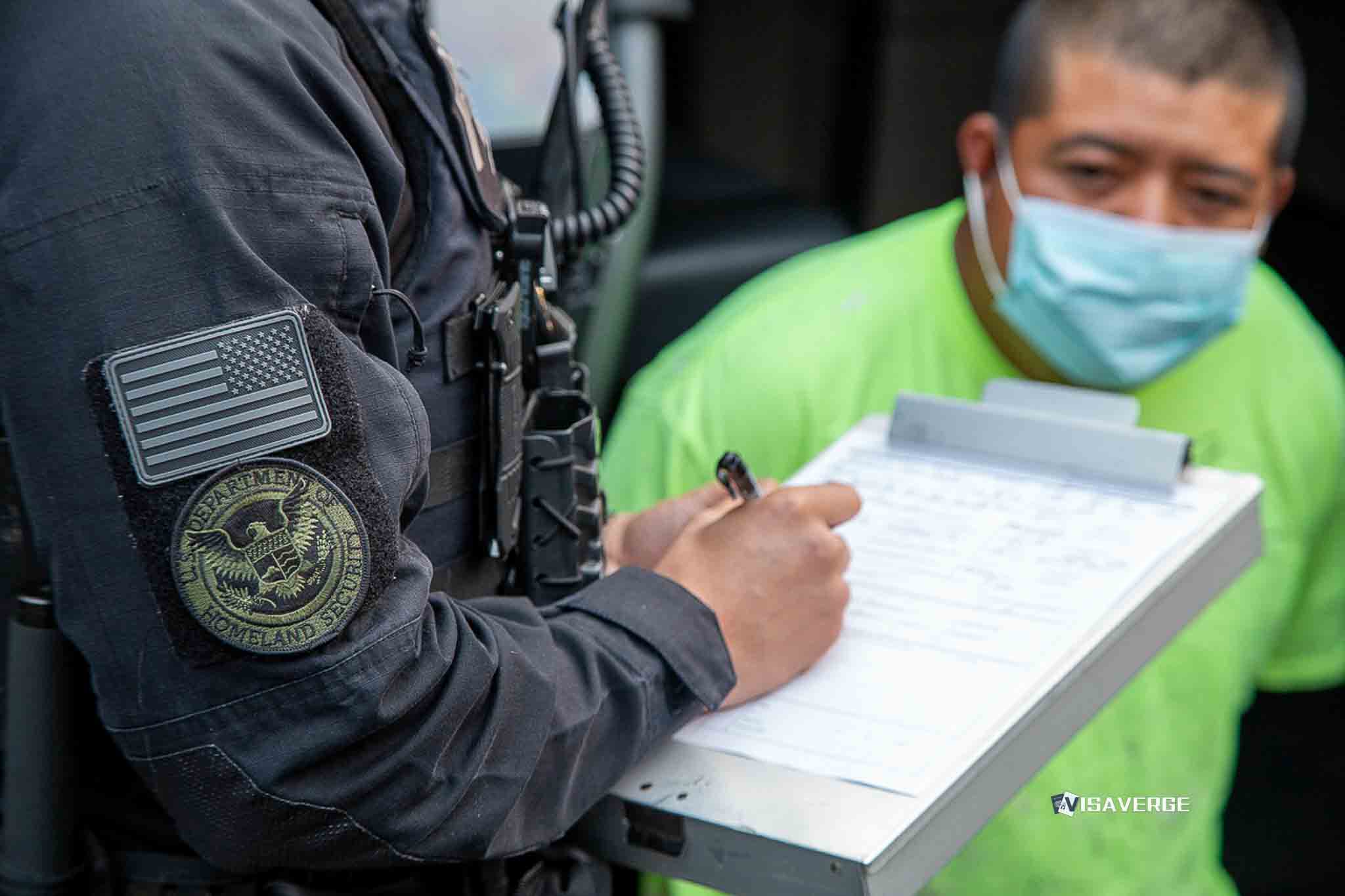

The administration’s approach is built on a rapid expansion of federal enforcement and sharp limits on humanitarian programs. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has added 10,000 agents, a move that has tripled daily arrests.

Protections that once offered breathing room are now mostly gone:

- Temporary Protected Status (TPS) and parole pathways for Colombians and several other groups have been ended or heavily restricted.

- Work permits tied to parole now last one year.

- New parole applications are no longer being accepted, closing a door many families used to remain lawfully present while pursuing longer-term options (VisaVerge.com).

Technology is also being used to accelerate departures. A new CBP Home app is pushing “self‑deportation,” allowing people to start voluntary departure without first going into detention. At the border, an executive order titled “Guaranteeing the States Protection Against Invasion” blocks access to asylum for anyone caught crossing between ports of entry, leading to summary removals with little chance to ask for protection.

The administration has further redirected resources to the border:

- More than 10,000 armed service members were reassigned to border support.

- 7,500 military personnel were deployed by late April.

The White House frames these moves as targeting criminals and deterring irregular crossings. Critics point to detention data showing that over 71% of migrants held by ICE in 2025 had no criminal background, raising concerns that long‑time residents and workers are being swept up along with recent arrivals.

How removals are happening: a quick pipeline

Inside the United States, the deportation pipeline has been accelerated into a faster, more expansive process:

- Apprehension: ICE and CBP conduct expanded sweeps and border operations, targeting recent crossers and long‑term residents.

- Detention: People are often held with limited access to lawyers, including under wartime authorities and new executive measures.

- Removal proceedings: Many face expedited processes, with asylum mostly blocked for those caught outside official ports.

- Flights: Commercial and military aircraft transport deportees; Colombia has agreed to accept unrestricted arrivals.

- Repatriation: Returnees are processed by Colombian authorities; long‑term support programs remain in development.

Families describe abrupt separations, missed court dates due to transfers, and confusion over work permits that are expiring sooner than expected. Employers report losing trained staff with little notice. Human rights groups say the measures rely on tough security language but are catching mostly non‑criminal migrants. The government counters that rapid removals have thinned border crossings and restored order.

High‑stakes standoff with Bogotá

Policy met diplomacy this spring when Colombia initially refused to accept deportation flights. President Gustavo Petro’s government pushed back, and the dispute quickly escalated.

- The United States warned of trade measures, including tariffs of up to 50% on Colombian goods.

- Threats also included travel bans and visa cancellations for officials.

- Hundreds of U.S. visa appointments at consulates in Colombia were canceled, stranding families and students who needed routine services.

A deal followed: Colombia agreed to receive deported nationals without limits, avoiding a wider trade conflict. To clear the backlog, U.S. authorities have relied on commercial charters and military aircraft. Flights are now operating regularly, and Colombian authorities are processing arrivals while working out plans for reintegration. For many returnees, however, support remains uncertain once they land.

The speed and scale of removals are straining communities on both sides of the border.

Economic and labor impacts

The enforcement surge has immediate labor-market consequences:

- The immigrant labor force in the United States has shrunk by 1.2 million since January 2025.

- Agriculture lost 6.5% of its workforce in four months, raising alarms about higher food prices and delayed harvests.

Labor groups warn that continued removals could deepen shortages in:

- Farming

- Food processing

- Service jobs that depend on steady, experienced workers

Employers report losing trained staff with little notice, increasing operational disruptions across multiple sectors.

Legal fights and available options for Colombians

Legal challenges are already underway. Civil rights lawyers are contesting:

- The asylum shutdown for those crossing between ports of entry

- The use of wartime statutes and expedited removal authorities in immigration contexts

Outcomes could reshape parts of the policy in coming months, but for now the rules remain in force. For official updates, see the Department of Homeland Security’s newsroom at https://www.dhs.gov/news.

For Colombian nationals weighing options, pathways have narrowed considerably:

- Unavailable or restricted: TPS, parole, and many humanitarian routes

- Remaining possibilities: family petitions, employment‑based routes for those who qualify, or waiting abroad for consular processing

Community advocates urge people to:

- Seek licensed legal help (avoid notarios)

- Keep copies of all past filings

- Attend all scheduled check‑ins to lower the risk of in‑absentia orders

Political context and public reaction

The sharp shift in 2025 represents a change from the more cautious approach seen late in the Biden years. Public opinion initially swung toward backing mass removals but has begun to edge back: a majority in new polls say the measures have gone too far.

- Supporters: Argue tough steps were overdue to secure the border and defend states.

- Critics: Warn families, workers, and students are paying the price for policies that close doors faster than courts can review them.

The present moment is notable for its speed, use of technology, and deep coordination across agencies and the military. The benchmark of 23,045 Colombians deported by mid‑year contrasts with 21,056 for all of 2024, fitting a wider pattern of record‑level enforcement affecting multiple nationalities at once.

As legal cases move forward and diplomatic ties with Bogotá adjust to the new flight schedules, those caught in the middle—parents, farmhands, and young adults with half‑finished degrees—are trying to plan for a future that keeps changing week by week.

This Article in a Nutshell

A rapid 2025 enforcement surge sent 23,045 Colombians home by June, surpassing 2024 totals. Expanded ICE, military support, app-driven self-deportation, and asylum limits accelerated removals, straining families, employers, and Colombia’s reception systems while legal challenges and diplomatic deals continue to unfold across borders and courts.