Holding and practical impact. In Matter of C-I-G-M- & L-V-S-G-, 28 I&N Dec. 451 (BIA 2025), the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) held that when the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) asserts an Asylum Cooperative Agreements (ACA) bar, the Immigration Judge should resolve ACA applicability as a threshold issue before reaching the applicant’s underlying asylum claim. The practical effect is immediate and stark: many asylum seekers may never receive a full merits hearing on past persecution or well-founded fear in their home country if the judge finds the applicant can be removed to a designated third country for protection processing.

In today’s enforcement climate—marked by the expanded use of Safe Third Country arrangements and public statements by DHS leadership, including Kristi Noem—this precedent gives DHS a procedural tool to seek pretermission (denial without full evidentiary development on the home-country claim). That changes case strategy, evidence needs, and hearing preparation in Immigration Court nationwide.

Legal background: the ACA bar in the INA and implementing regulations

The statutory basis for ACAs is INA § 208(a)(2)(A). It permits the United States to bar an asylum application if the applicant may be removed, pursuant to a bilateral or multilateral agreement, to a third country where the person’s life or freedom would not be threatened on a protected ground and where the person would have access to a “full and fair procedure” for determining a claim to asylum or equivalent protection.

The executive branch implemented ACA procedures through regulations first issued in 2019 and later defended and ratified against litigation risk. The current resurgence and expansion of ACAs has been paired with aggressive litigation positions in Immigration Court, where DHS often seeks early rulings on threshold eligibility bars.

Key facts that drove Matter of C-I-G-M- & L-V-S-G-

The BIA’s decision arose from removal proceedings in which DHS presented evidence that the respondents were subject to an ACA-based transfer to a designated third country. Rather than litigate the merits of the asylum claim first, DHS argued that the case should be disposed of on the statutory bar.

The respondents countered that they should be allowed to proceed to a full asylum hearing on the home-country claim. They argued that third-country safety, access to procedures, and individualized risk could not be fairly assessed on a thin record. They also raised due process concerns tied to timing, notice, and practical ability to gather evidence about a country they had never lived in.

The BIA agreed with DHS’s sequencing argument. It concluded that because INA § 208(a)(2) sets out threshold limits on eligibility, the Immigration Judge should decide whether the bar applies before moving to merits. As a result, the adjudication can end after the threshold inquiry.

What the BIA’s reasoning means in real hearings: “threshold first” becomes a fast track to denial

In many immigration courts, asylum cases already face short master calendar settings and heavy dockets. C-I-G-M- makes it easier for DHS to frame the first contested hearing around a narrow question: Is the respondent subject to an ACA and, if so, do any exceptions apply?

That narrowing has at least four downstream consequences:

- Record development shifts to the third country. Applicants now must often present evidence about conditions and individualized risk in the ACA destination country, not only the home country.

-

Short notice becomes outcome-determinative. If the respondent learns late that DHS will pursue an ACA transfer, gathering declarations, expert materials, or country reports may be difficult before the threshold hearing date.

-

Merits evidence may not be heard. Even strong home-country asylum claims can become irrelevant if the judge concludes the ACA bar applies.

-

Appellate posture changes. Appeals may focus on procedural defects, evidentiary burdens, and the adequacy of “full and fair” procedures in the third country, rather than the familiar asylum merits framework.

Burdens of proof and evidentiary challenges: proving danger in a country you never entered

A major controversy around modern ACA practice is the burden shift. Following C-I-G-M-, DHS commonly argues that once it establishes the respondent is covered by an ACA, the respondent must show—often by a preponderance of the evidence—that removal to the third country would be unsafe or that an exception applies.

That burden can be hard to meet, especially where the applicant:

- never transited through the third country,

- lacks family or community ties there,

- has no language ability relevant to that country,

- cannot quickly obtain reliable documentation about local protection procedures.

Critics describe this as the “fiction” problem: a legal label of “safe third country” may not match on-the-ground capacity. The statute, however, focuses on whether the applicant can access a full and fair protection process and whether threats exist in the third country. That is where C-I-G-M- forces litigants to concentrate early.

Warning (Practice Point): If DHS raises an ACA bar, treat the next hearing as potentially dispositive. Evidence about the third country may be as important as evidence about the home country.

Interaction with current policy: expanded ACAs and USCIS’s parallel posture

As of January 7, 2026, DHS has reported expanded or renewed ACA relationships with several countries, including Honduras and Guatemala, and it has signaled broader use of third-country transfers. DHS leadership messaging has reinforced that the United States is not the only protection destination, a view publicly articulated during the current administration led at DHS by Kristi Noem.

At the same time, USCIS has taken steps that affect affirmative asylum processing. A December 2, 2025 USCIS policy memorandum (PM-602-0192) placed a hold on Form I‑589 adjudications while vetting procedures are reviewed. While USCIS and EOIR operate in different lanes, the combined effect can be longer limbo for some applicants and more high-stakes, threshold litigation for others.

Circuit splits and conflicting authority: where federal courts may diverge

ACA litigation has produced varied federal court rulings over the years, and outcomes can depend on the circuit and on the specific agreement and administrative record. Some challenges have focused on:

- whether the third country truly offers “full and fair” procedures as required by INA § 208(a)(2)(A),

- whether agency implementation complied with the Administrative Procedure Act,

- whether particular applications violate due process in rushed proceedings.

Because C-I-G-M- is a BIA precedent, Immigration Judges must follow it unless a controlling circuit precedent requires a different approach. Practitioners should check circuit law on asylum bars, pretermission, due process, and standards for continuances when new bars are raised late.

Warning (Jurisdiction): Federal court review differs by circuit. What works in one jurisdiction may fail in another. Preserve issues and build a record for appeal.

Dissenting opinions

The BIA issued Matter of C-I-G-M- & L-V-S-G-, 28 I&N Dec. 451 (BIA 2025) as a precedential decision. Any separate opinions would matter for future litigation framing. Practitioners should review the decision text closely for concurrences or dissents and cite them where they support due process or record-development arguments. (This article focuses on the central holding and its common courtroom use.)

Practical takeaways for attorneys and asylum seekers

- Expect early ACA litigation. DHS may file a motion to pretermit or raise the ACA bar at the master calendar stage. Prepare as if the first individual hearing could end the case.

-

Build a third-country record fast. Collect country conditions materials about the ACA destination country, including NGO reports, U.S. government reporting where available, and expert declarations when feasible.

-

Seek continuances with specificity. If notice is short, document what evidence you need, why it is material, and the steps already taken to obtain it. Make a clear record for appeal.

-

Press “full and fair procedure” arguments carefully. INA § 208(a)(2)(A) is not satisfied by a label alone. The inquiry often turns on what procedures exist in practice and whether the respondent can access them.

-

Coordinate USCIS and EOIR strategy. Where clients have parallel pathways, counsel should assess how USCIS holds or delays interact with EOIR timelines, work authorization eligibility, and custody decisions.

Deadline (Court Practice): File witness lists, exhibit packets, and motions by the Immigration Judge’s local deadlines. Missing a filing deadline can effectively decide an ACA threshold hearing.

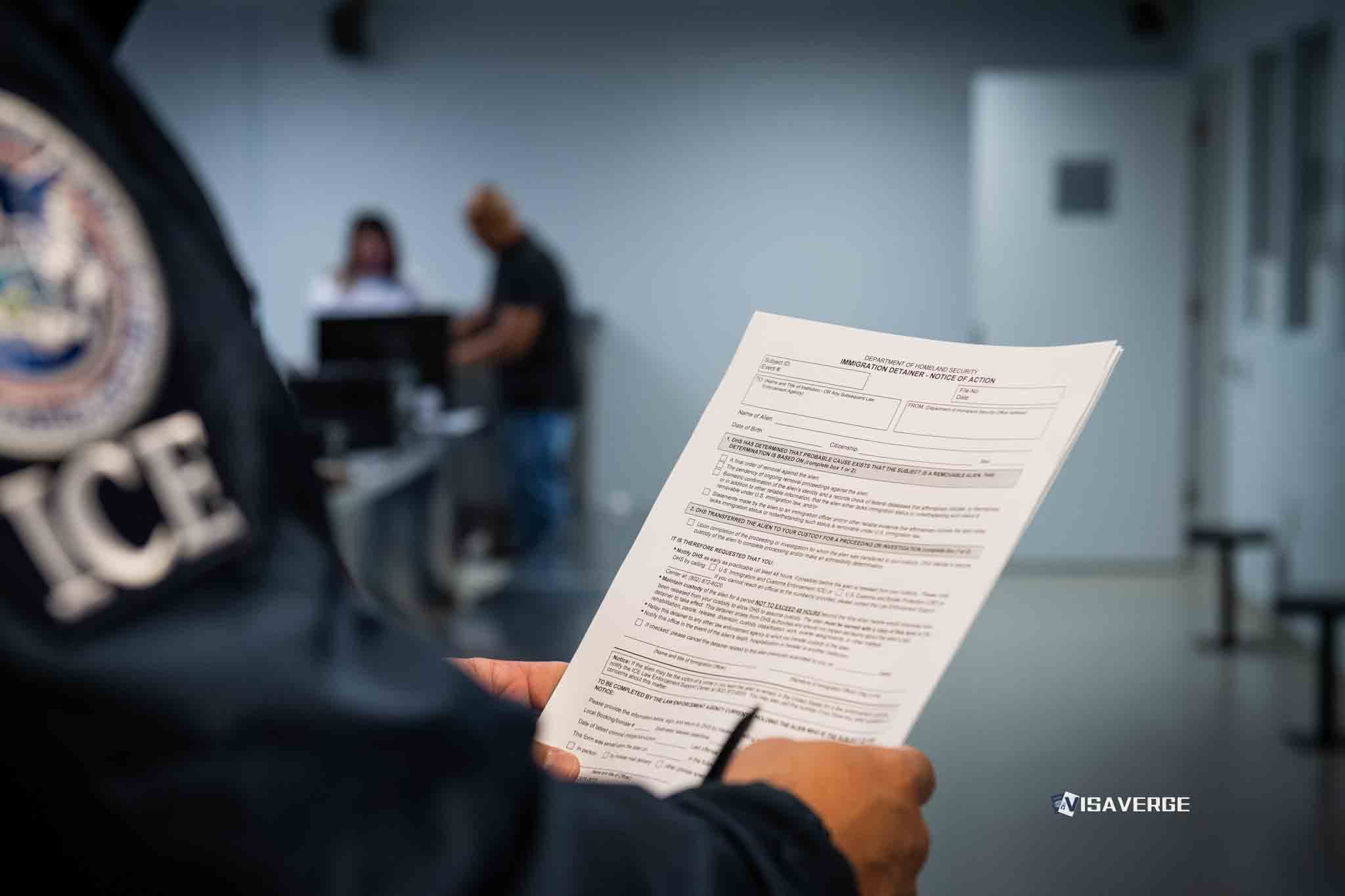

Warning (Travel/Detention): Third-country transfer cases can move quickly. If ICE custody is involved, consult counsel immediately about bond, habeas options, and how transfer logistics affect court access.

Where to find official primary materials

For readers tracking ACA policy and asylum processing changes, start with official sources:

- EOIR (Immigration Court and BIA information): https://www.justice.gov/eoir

- USCIS policy and leadership statements: https://www.uscis.gov/laws-and-policy/policy-manual

⚖️ Legal Disclaimer: This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.

Resources:

– AILA Lawyer Referral

The BIA’s 2025 ruling establishes that ACA bars are threshold issues that judges must resolve before reaching the merits of an asylum claim. This allows DHS to expedite denials by focusing on third-country removal. Consequently, asylum seekers must now produce evidence regarding risks in designated third countries like Guatemala or Honduras, shifting the burden of proof and potentially bypassings hearings on home-country persecution entirely.