- 01The Philippine Embassy warned teachers about scams falsely promising Green Cards through J-1 visas.

- 02The J-1 visa is a temporary cultural exchange program, not a direct path to residency.

- 03Most teachers face a two-year home-residency requirement that is difficult to waive.

(WASHINGTON, D.C.) The J-1 exchange visitor program visa is a temporary, non-immigrant visa meant for cultural exchange, not a direct route to permanent residency or U.S. citizenship.

A January 7, 2026 warning from the Philippine Embassy in Washington, D.C. says scammers are targeting filipino teachers with false promises that the program leads to a Green Card.

For many teachers, the bigger issue is the two-year home-country physical presence requirement under INA 212(e). That rule can block a future Green Card or some work visas unless the person returns home for two years or gets a waiver.

waivers exist, but they are hard to win and never automatic.

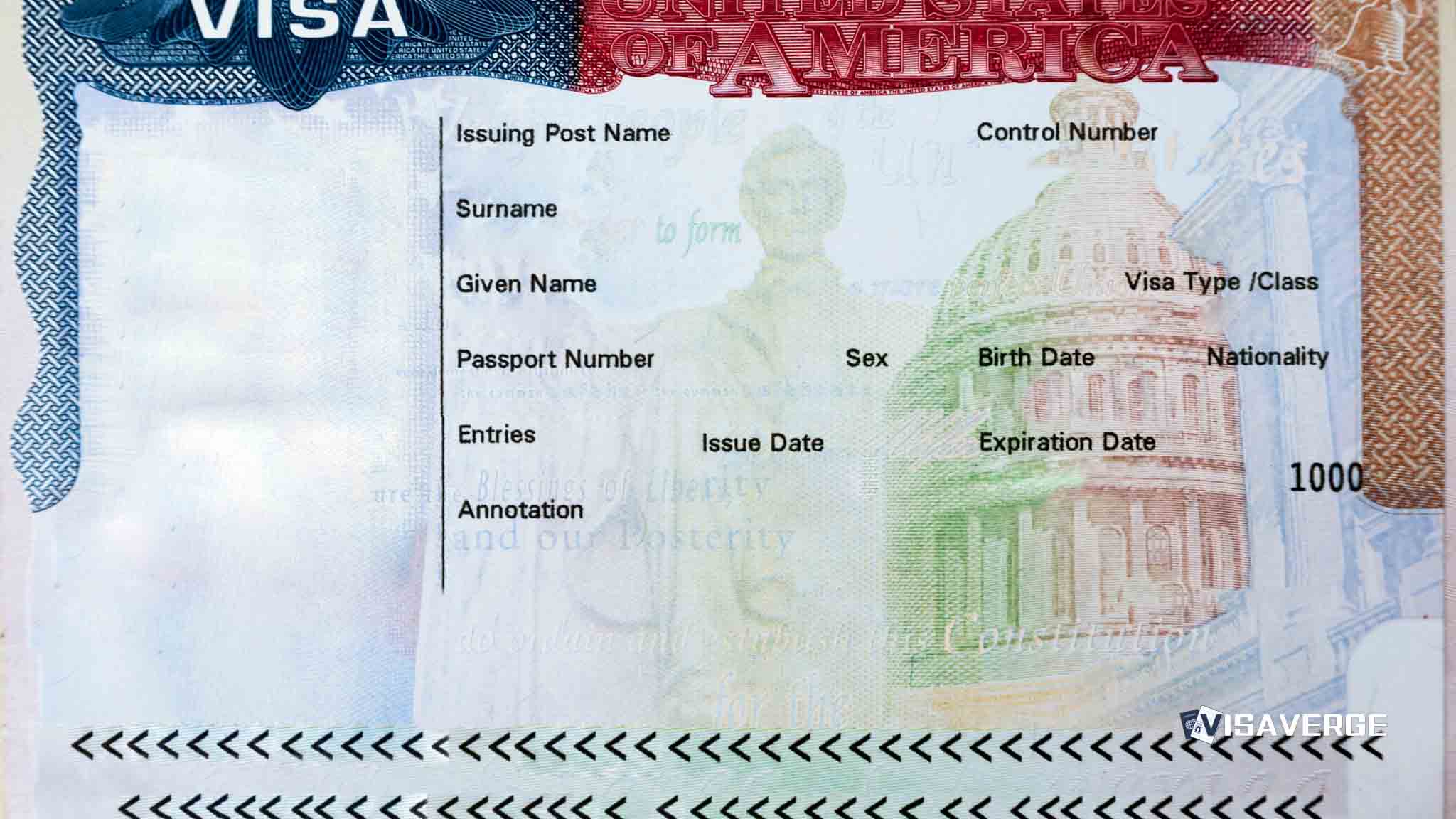

What the J-1 visa is designed to do—and what it isn’t

The J-1 category covers exchange visitors who come to the United States for a specific, approved program. The point is professional and cultural exchange with a clear end date.

That design matters because the J-1 is not the same as a long-term work pathway. It is not an “employment visa,” and it is not a promise of later immigration benefits.

Many participants do later explore lawful ways to stay in the United States. But the J-1 itself does not convert into a Green Card plan just because someone found a job, built a life, or paid a recruiter.

Scammers exploit that gap. They often sell a story that sounds simple: enter on J-1, teach for a year or two, then “adjust” to permanent status. That storyline leaves out the legal barriers that apply to many J-1 teachers.

VisaVerge.com reports that teacher-focused exchange categories are repeatedly targeted because applicants are motivated, time-sensitive, and often working through third parties.

January 7, 2026: Embassy warning and why it matters

In its January 7, 2026 advisory, the Philippine Embassy in Washington, D.C. put the key point in plain language: “The Philippine Embassy in Washington, DC, reminds the public that the J-1 Exchange Visitor Program visa is a temporary, non-immigrant program designed for cultural exchange. It is not an employment or work visa.”

The Embassy also warned against assuming the program leads to long-term status: “Filipino teachers should be aware that participation in the program does not lead to U.S. permanent residency or citizenship.”

The advisory was tied to reports of illegal recruiters and people posing as immigration lawyers. The pattern described is familiar: large fees, rushed sign-ups, and verbal assurances that disappear once money changes hands.

The Embassy also highlighted that many teachers face INA 212(e). It stated: “Filipino teachers are subject to the two-year home-country physical presence requirement. Waiver of this requirement is difficult to obtain, not guaranteed, and requires exceptional hardship or highly meritorious circumstances.”

How U.S. screening works: non-immigrant intent and a stricter climate

U.S. rules treat the J-1 as a temporary stay, so visitors must be able to show they plan to leave after the program ends. USCIS describes this as “non-immigrant intent” in its policy guidance for exchange visitors.

That expectation affects real decisions. It shapes questions at visa interviews. It also shapes entry screening at the airport and later benefit requests.

Policy shifts can also change how closely officers review cases. Presidential Proclamation 10998, implemented on January 1, 2026, intensified vetting and restricted entry for various categories to “protect the security of the United States.”

An updated USCIS Policy Memorandum dated January 7, 2026 placed a hold on various benefit adjudications for certain high-risk categories. Even when a case is fully legitimate, a stricter posture often means slower timelines and more requests for proof.

In that environment, the safest strategy is simple: tell the truth, keep documents consistent, and avoid any step that could be seen as misrepresentation.

INA 212(e): the two-year rule, what it blocks, and what a waiver really means

The two-year home-country physical presence requirement under INA 212(e) applies to many J-1 holders, especially in the “Teacher” or “Government-Funded” categories. If the rule applies, the person must spend two years physically present in their home country after the program.

Until that requirement is met or waived, it can block eligibility for:

- An immigrant visa or a Green Card-based pathway tied to immigrant intent

- Certain work visas, including H and L categories

A waiver is the legal mechanism that removes that barrier. The Embassy warned that a waiver is “difficult to obtain” and “not guaranteed.” The process is multi-agency and evidence-heavy, involving both Philippine government review and the U.S. Department of State.

Two waiver concepts that commonly come up are:

- No Objection Statement (NOS), which is not a personal right and can involve home-government review

- Exceptional Hardship, which requires strong evidence and a detailed case theory

None of these paths turn the J-1 into a promised track to permanent status. They are separate processes with high stakes and long-term consequences.

Overstays and status violations: how small mistakes become big bars

The Embassy warning also addressed overstays directly. Overstaying a J-1 is described as a “serious violation of U.S. immigration law,” with risks that include deportation and a 3- to 10-year ban from the United States.

Those outcomes often start with everyday choices:

- Working outside the approved program terms

- Staying past the authorized end date

- Trusting an agent who says, “Just file something” to buy time

It also flagged “frivolous asylum claims” as a tactic pushed by unscrupulous agents. That approach can permanently damage future eligibility and expose the person to removal.

It’s also important to separate lawful options from wishful thinking. A lawful change of status or a future petition is not the same as a guaranteed plan.

Any step that relies on false documents, fake job offers, or coached answers creates a record that can follow someone for years.

A practical journey map for teachers: safer choices at each stage

Start with the assumption that the J-1 is temporary. Then plan the process like a compliance project.

Stage 1: Vet the offer before paying (days to weeks). Ask for written program details, the sponsor’s name, and the full fee schedule. Get refund rules in writing.

Stage 2: Confirm program terms and keep proof (throughout). Save contracts, email threads, and instructions from the sponsor. Keep copies of your program documents, including Form DS-2019.

Stage 3: Track INA 212(e) early (before long-term plans). If your long-term goal is permanent residency, confirm whether the two-year rule applies before signing multi-year commitments or making family plans.

Stage 4: Maintain status without shortcuts (daily behavior). Don’t accept side work or off-program roles. Don’t rely on “fixers” who promise to handle immigration through connections.

Stage 5: Get qualified help for long-term goals (when stakes rise). Consult a qualified U.S. immigration attorney before any waiver strategy or major filing, especially if a recruiter is pushing urgent action.

How to verify claims using official sources—and build your records

Use a simple verification workflow before trusting any recruiter or “consultant.”

1) Cross-check U.S. government guidance. Use the official USCIS Exchange Visitors page for baseline rules. That USCIS page is also a reliable starting point for non-immigrant intent expectations.

2) Verify J-1 basics with the Department of State. Review the U.S. Department of State J-1 visa basics to confirm how the category works and what documents govern the stay.

Finally, keep a “compliance folder” in one place, digital and printed. Include your DS-2019, sponsor communications, address updates, travel history, and proof that you followed program terms from day one through departure.

The Philippine Embassy is alerting Filipino teachers that J-1 visas are temporary and do not guarantee U.S. residency. Scammers often hide the ‘two-year home-country physical presence requirement,’ which blocks future Green Cards unless a difficult waiver is obtained. In early 2026, new U.S. policies have intensified vetting for these categories, making it essential for applicants to verify sponsors and strictly follow all immigration rules to avoid bans.