(NEW JERSEY) — A practical defense strategy for noncitizens in New Jersey right now starts with a clear premise: the Immigrant Trust Directive remains active as an Attorney General policy, the Safe Communities Act is now signed, and the most durable “protection” in any individual case still comes from federal immigration relief pursued with counsel—not from state politics.

New Jersey’s Immigrant Trust Directive (ITD) is intended to limit when state and local agencies will voluntarily assist federal immigration enforcement. It sets cooperation rules about information-sharing and custody handoffs.

What happened

On Jan. 20, 2026, Gov. Phil Murphy declined to turn the ITD into a statute, letting the codification bill die by a pocket veto on his last day. A pocket veto in New Jersey typically means a bill expires without the governor’s signature at the end of the legislative session.

It differs from signing, which makes a bill law, and from a veto override process. Advocates often prefer codification because it is harder to undo and can be enforced like any statute. Officials may avoid codification when they believe it invites fresh litigation, including federal preemption challenges.

At the same time, Murphy signed the Safe Communities Act, which directs the Attorney General to produce “model policies” addressing enforcement activity around sensitive locations such as schools, hospitals, and houses of worship. As a defense-oriented matter, these frameworks can shape day-to-day encounters, especially where local agencies control access, records, or facility policies.

Still, even strong state policy does not eliminate federal authority to arrest, detain, or remove under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). That split—state non-cooperation versus federal enforcement power—is the core concept attorneys must explain to clients.

Messaging, perception, and immediate risks

For readers watching the messaging cycle, timing matters because rhetoric often changes behavior before the law changes. The sequence surrounding Jan. 20 included federal statements and announcements that were not directly tied to New Jersey’s pocket veto, but could increase fear in immigrant communities.

It is important to separate three things: (1) enforcement rhetoric, (2) criminal investigations or indictments, and (3) actual state policy changes. Confusing those categories can lead to avoidable mistakes, like missing court dates or skipping mandated check-ins.

The timeline immediately preceding the governor’s action also illustrates how quickly “sanctuary” debates can spill across jurisdictions. In mid-January, ICE messaging criticized sanctuary policies elsewhere. USCIS also publicized New Jersey-related indictments involving alleged fraud tied to citizenship applications.

Then, on Jan. 19, DHS leadership issued broad warnings about civil fines and removal for unlawful presence. None of those items, standing alone, proves a coordinated response to Trenton. But in practice, such announcements can raise the perceived risk of travel, reporting, or even calling police as a crime victim.

Legislative details and differences between measures

The legislative details matter because each bill would have operated differently in court. The ITD codification bill (A6310/S5038) would have moved a directive into statutory footing, reducing the chance that a future administration could change it quickly by internal memo.

The Privacy Protection Act bill (A6309/S5037), which Murphy also declined to sign, would have addressed collection and sharing of sensitive data by state and local entities. Murphy cited drafting and funding risks, including potential federal funding exposure.

The Safe Communities Act (A6308/S5036), by contrast, is structured as a mandate for model policies and implementation guidance. That means it may affect agency practice without creating the same kind of directly enforceable private right.

How those differences affect defense strategy

This is where defense strategy becomes concrete: a directive is an executive-branch rule for agency conduct; a statute is binding law passed by the legislature; and “model policies” are often guidance that can be adopted, adapted, or interpreted.

A noncitizen’s lawyer must identify which category applies in the client’s county and which entity controls the interaction. For example, a local jail’s booking and release practices implicate ITD-type cooperation limits. A courthouse, school, or hospital encounter may implicate “sensitive location” guidance. But an ICE arrest decision remains a federal choice, reviewed through federal channels.

State “sanctuary-style” limits usually restrict voluntary cooperation by state and local agencies. They typically do not bar federal agents from acting under federal law.

As of Jan. 21, the ITD remains in effect as an Attorney General policy, not as codified law. That distinction affects durability: policies can be revised faster than statutes, especially after elections or an Attorney General transition.

It also affects litigation posture. Murphy’s explanation was essentially defensive: he described codification as reopening the door to judicial scrutiny that could jeopardize an existing directive. For defense counsel, the operational question is narrower: what does the ITD instruct agencies to do today, and what exceptions remain?

Carve-outs, “final order” implications, and federal causation

Public summaries of the ITD commonly reference carve-outs for serious criminal matters and for circumstances involving a final order of removal. “Final order” is a technical term in removal proceedings, often following an Immigration Judge order that has become administratively final after appeal deadlines.

The presence of a final order can change detention risk and ICE priorities. Still, state carve-outs do not decide federal custody. They only shape whether local agencies will affirmatively assist.

Importantly, there was no DHS press release specifically attributing any federal action to Murphy’s pocket veto. That matters because causation claims can overstate the immediate legal impact on the ground.

Political transition and advocacy reactions

In political terms, the transition to incoming Gov. Mikie Sherrill adds uncertainty because non-codified directives can be tweaked more easily than statutes. Advocacy groups criticized the pocket veto because they want permanence, uniformity, and enforceability.

Murphy’s stated rationale centered on litigation exposure and federal preemption arguments. In immigration law, preemption questions can arise when state measures are framed as regulating immigration itself rather than state agency conduct.

Readers should treat political statements as signals, not as immediate rule changes. The checklist questions that matter day-to-day are scenario-specific, such as which agency is asking for what assistance, and whether the request is discretionary or mandatory under state policy.

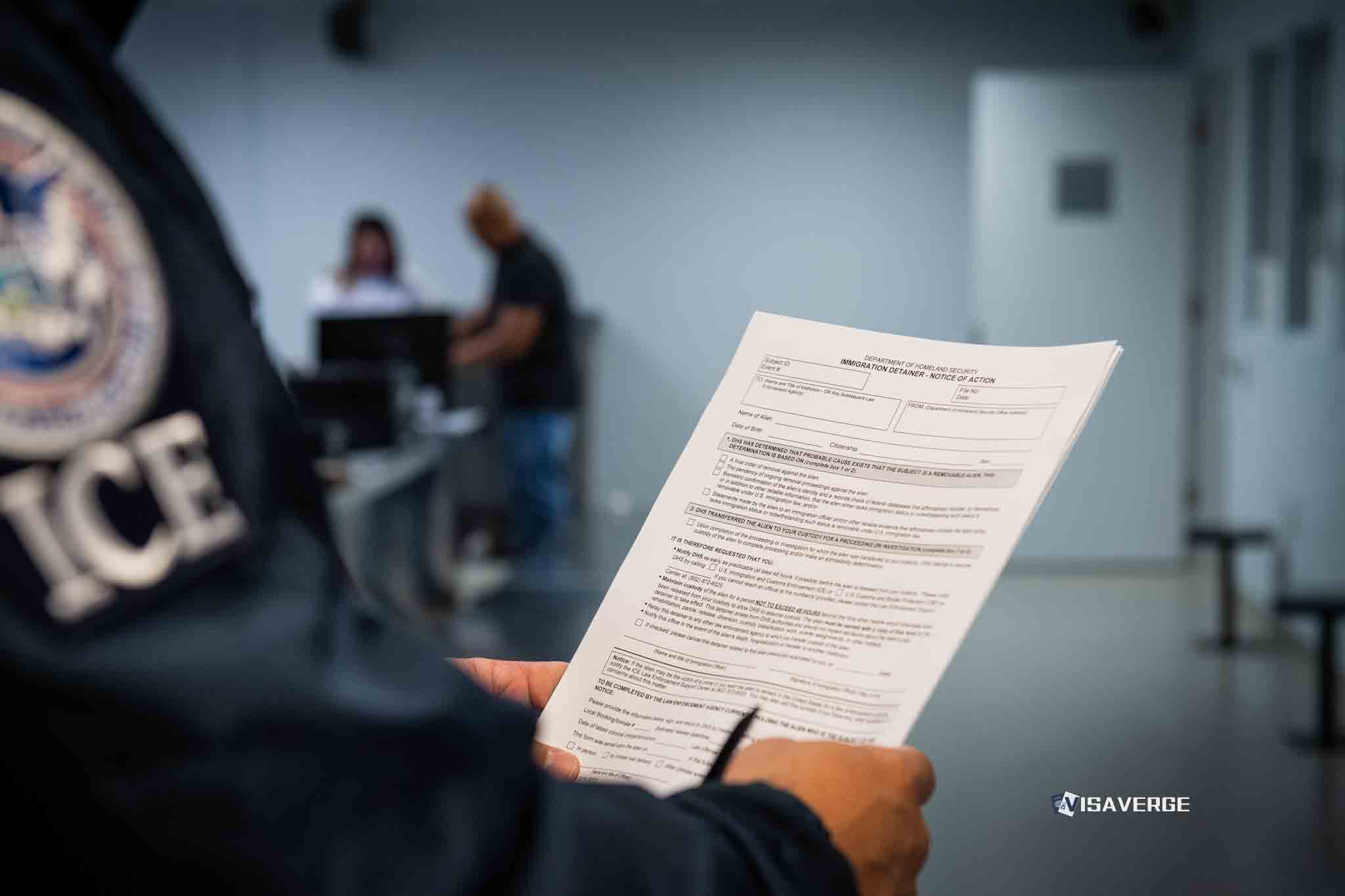

If you are presented with an ICE detainer, “notification” request, or interview request, do not sign anything without speaking to counsel. Ask for documents in writing.

Federal relief options and procedural risks

For individuals who are or may be in removal proceedings, the strongest defense is often federal relief eligibility, pursued quickly. Common forms of protection include asylum under INA § 208, withholding of removal under INA § 241(b)(3), and protection under the Convention Against Torture regulations at 8 C.F.R. §§ 1208.16–1208.18.

Other defenses may include cancellation of removal under INA § 240A, or bond arguments under INA § 236 where eligible. Each has statutory requirements and bars. Asylum, for example, has a one-year filing deadline with exceptions, and serious crimes can bar asylum and withholding.

Cancellation turns on continuous presence, qualifying relatives, hardship, and disqualifying convictions. These standards are technical, and outcomes vary by circuit.

If you are in immigration court, missing an EOIR hearing can result in an in absentia removal order. If you move, file address changes promptly with EOIR and USCIS when required.

Evidence and typical case-building practices

Evidence is typically what separates a viable defense from a fast removal order. For humanitarian relief, lawyers commonly build identity, entry, and residence records; detailed declarations; corroborating affidavits; medical or psychological records where relevant; and country-conditions evidence.

For cancellation, counsel often focuses on tax filings, school and medical records for children, proof of caregiving duties, and documentation of any lawful entries or prior proceedings. For bond, evidence often includes stable address proof, community ties, employment records, and criminal-disposition documents showing case outcomes.

A single missing certified disposition can derail an otherwise strong claim.

Factors that strengthen or weaken cases

- Strengthening factors: prompt filing, clean and well-documented criminal dispositions, consistent testimony, and early issue-spotting on inadmissibility and deportability grounds.

- Weakening factors: prior removal orders, prior fraud findings, multiple entries, or criminal allegations without certified court outcomes.

- System limits: New Jersey’s ITD and the Safe Communities Act may reduce certain local cooperation pathways, but they do not erase federal charging authority.

Travel can carry special risk. Lawful permanent residents, visa holders, and applicants with pending cases can face questioning at ports of entry. Consult counsel before international travel.

Practical steps and verification

To verify updates, start with primary sources and check dates and bill numbers. The Governor’s Office announcement about the Jan. 20 action is the most direct record of what was signed and what lapsed.

For the operative ITD guidance, use the New Jersey Attorney General’s page on the Immigrant Trust Directive. For federal enforcement announcements, distinguish DHS-wide messaging from case-specific actions by checking the DHS newsroom and the USCIS newsroom.

Publication date, agency letterhead, and cited legal authority usually tell you whether a document is binding, advisory, or political messaging.

Bottom line

The pocket veto leaves the ITD in place but not codified, while the Safe Communities Act pushes model policies on sensitive locations. That combination can shape local interactions, but it is not a substitute for federal defenses.

Because small facts can trigger bars, detention, or expedited procedures, attorney representation is critical—especially for anyone with arrests, prior orders, or alleged fraud.

⚖️ Legal Disclaimer: This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.

Resources

– AILA Lawyer Referral: AILA Lawyer Referral