(NEW JERSEY) — As New Jersey considers a first-of-its-kind state portal to track ICE activity, critics warn the plan may clash with federal enforcement and risk data privacy, while officials and advocates float competing visions for supervision and protection.

Governor Mikie Sherrill’s new administration is putting immigration enforcement back on the state’s front burner. The idea is simple on its face: create an ICE Tracking Portal where residents can document federal immigration activity they witness. The fight around it is not simple. It sits at the fault line between state authority and DHS (Department of Homeland Security) power, and it raises a basic question: can a state increase accountability without creating new privacy risks for the same communities it wants to protect?

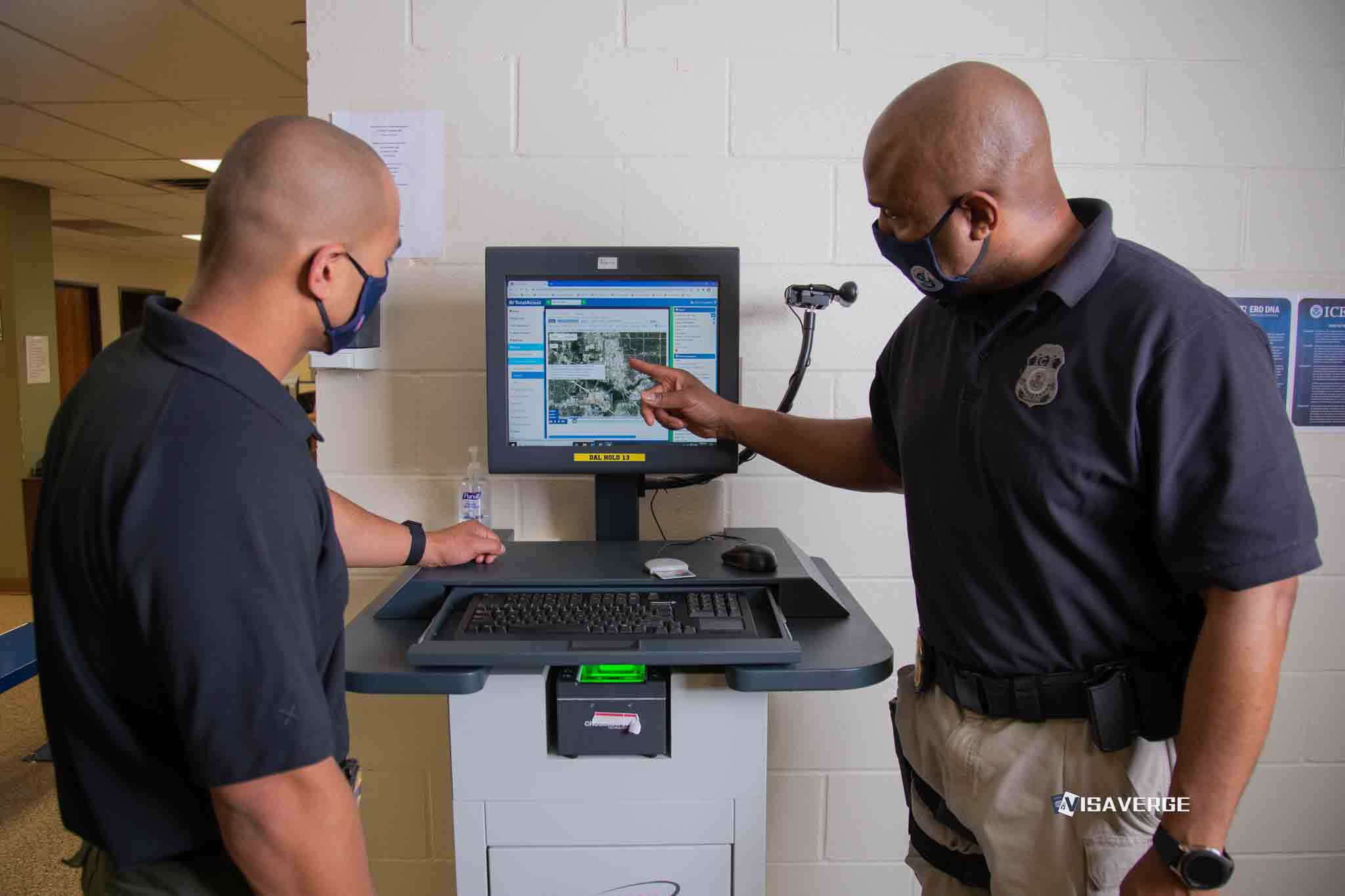

State leaders, immigrant rights groups, local police, and federal agencies all have different incentives. New Jersey’s governor’s office can shape state privacy practices and decide how state property is used. Local law enforcement can choose how much it cooperates with federal requests, within state rules. DHS and ICE (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement), however, control federal arrests, detention decisions, and many operational details of enforcement. A state portal cannot stop a federal arrest. It can, at most, document what happened and influence state-level cooperation norms.

1) Context and Stakeholders: Who controls what

Early-term initiatives often set the tone for an administration. Governor Mikie Sherrill, inaugurated in January 2026, is framing the ICE Tracking Portal as an accountability tool and a warning system for residents. That puts New Jersey on a collision course with federal officials who view the plan as interference.

Phil Murphy’s final-day veto of legislation tied to the Immigrant Trust Directive is part of the backdrop. That veto kept limits on local cooperation from being locked into statute, leaving advocates worried that informal protections can be weakened. Meanwhile, state officials face competing pressures: demonstrate oversight of enforcement that affects local communities, but avoid actions that DHS could argue obstruct federal law.

Authority is split. States can set rules for their own property, control their own records systems, and create privacy standards for state-run platforms. Federal agencies can still conduct enforcement actions under federal authority, including in public spaces and many non-state locations. That boundary shapes every claim being made about the portal.

2) New Jersey’s ICE Tracking Portal Proposal: what it is, and what it can’t do

Governor Sherrill has described a state-run “citizen portal” designed to collect public reports of ICE activity. On January 28, 2026, during an interview on The Daily Show, she said:

“We are going to be standing up a portal so people can upload all their cell phone videos and alert people. Like, if you see an ICE agent in the street, get your phone out. We want documentation.”

The ICE Tracking Portal is envisioned as a website where residents could upload videos, photos, and location data linked to ICE activity. The stated goal is accountability—building a record that can be reviewed, shared with oversight bodies, or used to spot patterns.

A state-run portal like this typically lives or dies on design choices:

- Intake: what the portal accepts (media, addresses, time stamps) and what it refuses (personal identifiers, rumors, doxxing).

- Review and moderation: who checks reports, how quickly, and what gets published versus kept internal.

- Retention policies: how long submissions are stored and who can access raw files.

- Sharing rules: whether submissions are shared with local police, the NJ Office of the Attorney General, or other agencies.

Those mechanics matter because a portal can become a public-records magnet. If submissions are stored by the state, residents may worry that data could later be demanded in litigation, requested through records processes, or sought by federal investigators. The state can adopt privacy-focused policies, but no design can guarantee absolute protection against every legal demand.

Sherrill’s administration also announced a ban on ICE using any state-owned property to stage raids. That type of restriction is most credible on state-controlled spaces like state buildings and state parking lots. Limits appear quickly in practice. Federal agents acting under federal authority may still operate in many public areas, and states generally cannot block federal enforcement outright.

Communities should also be clear-eyed about timing. Documentation can help after the fact—supporting complaints, journalism, litigation, or legislative oversight. It rarely provides real-time protection during an encounter. Fast-moving enforcement actions may be over before any report is reviewed.

3) Official DHS and ICE Responses: “obstruction” claims and enforcement messaging

Federal officials have answered with sharp language. Their public posture signals two things at once: continued enforcement activity and resistance to transparency demands that could expose methods.

On January 2, 2026, DHS Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin said:

“ICE law enforcement secures our streets every single day including over the holiday season. They rang in the New Year with the removal of more disgusting monsters including pedophiles, murderers, and fraudsters from American neighborhoods. American families have safer communities in 2026.”

That framing emphasizes public safety and high-harm cases. It also sets up DHS’s argument that efforts to track agents could endanger them.

On January 29, 2026, after reports about expanded detention and enforcement, an ICE spokesperson stated:

“Every day, DHS is conducting law enforcement activities across the country to keep Americans safe. It should not come as news that ICE will be making arrests in states across the U.S. and is actively working to expand detention space.”

Residents can reasonably infer that DHS expects enforcement to continue across New Jersey and the region. Another uncertainty is what information federal agencies will disclose about tactics and technology use, especially when they label details “law enforcement sensitive.”

On the same date, DHS responded to reporting about biometric and AI tracking concerns by saying:

“ICE’s use of innovative technologies in investigations is ‘no different’ than other law enforcement agencies. We are not going to divulge law enforcement sensitive methods.”

That stance points to a familiar federal pattern: defend technology use as standard policing while limiting public detail.

| Actor | Position on portal | Concern/Claim |

|---|---|---|

| Governor Mikie Sherrill | Supports creating the ICE Tracking Portal and restricting ICE staging on state-owned property | Says documentation increases accountability; criticizes agents operating “with masks and no insignia” |

| DHS (Department of Homeland Security) | Opposes state tracking efforts | Frames portal as obstructing federal law and risking agent safety |

| Tricia McLaughlin | Public defender of DHS enforcement posture | Argues enforcement removes dangerous offenders and improves safety |

| ICE (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement) | Signals continued nationwide enforcement and detention expansion | Says arrests across the U.S. should be expected and detention space is expanding |

| Phil Murphy | Vetoed legislation to codify the Immigrant Trust Directive | Warned codifying limits could invite federal pushback and court fights |

| Nedia Morsy | Skeptical of portal alone; critical of veto | Calls veto a “failure of leadership” and wants binding protections |

| Surbhi Patel | Warns portal may not protect people fast enough | Raises fears about data exposure and slow response |

| Make the Road Action New Jersey | Wants stronger, enforceable limits on cooperation and data sharing | Pushes legislative protections beyond a reporting website |

| NJ Alliance for Immigrant Justice | Wants laws that reduce cooperation and tighten privacy | Seeks real safeguards, not only documentation |

| NJ Office of the Attorney General | Key state institution for guidance and policy implementation | Maintains resources tied to the Immigrant Trust Directive |

4) Advocates’ perspective: why “a portal” is not the same as protection

Nedia Morsy, director of Make the Road Action New Jersey, attacked the January 20, 2026 veto by Phil Murphy as a “failure of leadership.” For many advocates, that veto matters because it kept the Immigrant Trust Directive from becoming a statute. A directive can guide agencies. A law is harder to reverse.

Surbhi Patel of the NJ Alliance for Immigrant Justice has also questioned whether the ICE Tracking Portal could help in the moment. Speed is one issue. Privacy is the other. If residents upload location-tagged videos, they may worry that the information could be “lost in the ether” or later seized by federal authorities. Even if the portal is meant to watch ICE activity, a poorly designed system could end up exposing community members, witnesses, or bystanders.

Advocates are pressing Governor Mikie Sherrill to pair any portal with legislation:

- Safe Communities Act: aimed at reducing police-ICE collaboration and limiting the ways local systems feed federal enforcement.

- Privacy Protection Act: aimed at stronger controls on data sharing, with clearer rules about when state or local data can be shared with federal agencies.

Portal design choices intersect with these demands. Anonymity options may reduce fear of retaliation, but they can also increase false reports. Short retention periods may lower privacy risk, but they can limit oversight value. Tight access controls can help, yet they require real administrative discipline and clear audit trails.

5) Key statistics and context: why attention is rising now

A nationwide rise in ICE arrests has helped fuel demand for documentation and oversight. When communities believe enforcement is increasing, they also tend to seek tools that create a record of what happens on the ground.

Detention expansion reports add another pressure point. Real estate moves—such as acquiring large warehouse-type facilities—can change local risk perceptions quickly, especially when tied to the possibility of mass detention capacity near residential areas. Roxbury, New Jersey has been mentioned in reported acquisition activity, a detail that can intensify local concern even before any facility change is finalized.

New Jersey’s demographics also shape the debate. The state has the second-largest immigrant population in the U.S. per capita, and proximity to Philadelphia (ICE Philadelphia) can heighten attention to regional enforcement teams. Still, statistics are snapshots. Enforcement patterns can shift by region, leadership priorities, and operational constraints.

6) Official sources and next steps: how to verify claims and track changes

Practical steps start with separating proposals from enforceable rules. A portal announcement is not the same as a launched platform with published privacy terms. A property restriction claim is not the same as a tested policy that has been enforced during an on-the-ground operation.

USCIS is a separate agency from ICE, and a state tracking portal does not change USCIS processes for applications or status determinations. The portal is about documenting ICE activity, not deciding immigration benefits. For federal updates, stick to official agency statements rather than viral clips.

Federal preemption is the legal reality in the background. New Jersey may change state cooperation practices and state data handling. DHS and ICE still retain federal enforcement authority. Documentation can support oversight and legal claims later, but it typically does not stop an encounter in progress.

Personal readiness can be calm and practical. Keep copies of immigration filings, IDs, and attorney contact information in a place you can access quickly if an enforcement encounter occurs.

Check official sources (ICE Newsroom, DHS statements, NJ Office of the Attorney General) for updates; review your own data-sharing practices and attorney contacts in case of enforcement encounters

This article discusses policy proposals, federal enforcement actions, and legal boundaries. Readers should consult official sources for updates and consult qualified legal counsel for individual circumstances.