(BERLIN, GERMANY) — Sudanese filmmakers Mohammed Alomda and Amjad Abu Alala withdrew from the Berlinale Co-Production Market after German visa denials cited “migration risk.”

Their project, “Blue Card,” had been selected for the market, but the filmmakers could not proceed as planned after the rejections, Screen Daily reported on February 14, 2026, in an article by Michael Rosser.

The withdrawal removed “Blue Card” from an industry platform designed to connect projects with partners, and it cut off the filmmakers’ access to in-person meetings during the 2026 Berlinale, which is ongoing in Berlin.

Alomda and Abu Alala are acclaimed creators, and Screen Daily described Abu Alala as known for Cannes-winning work.

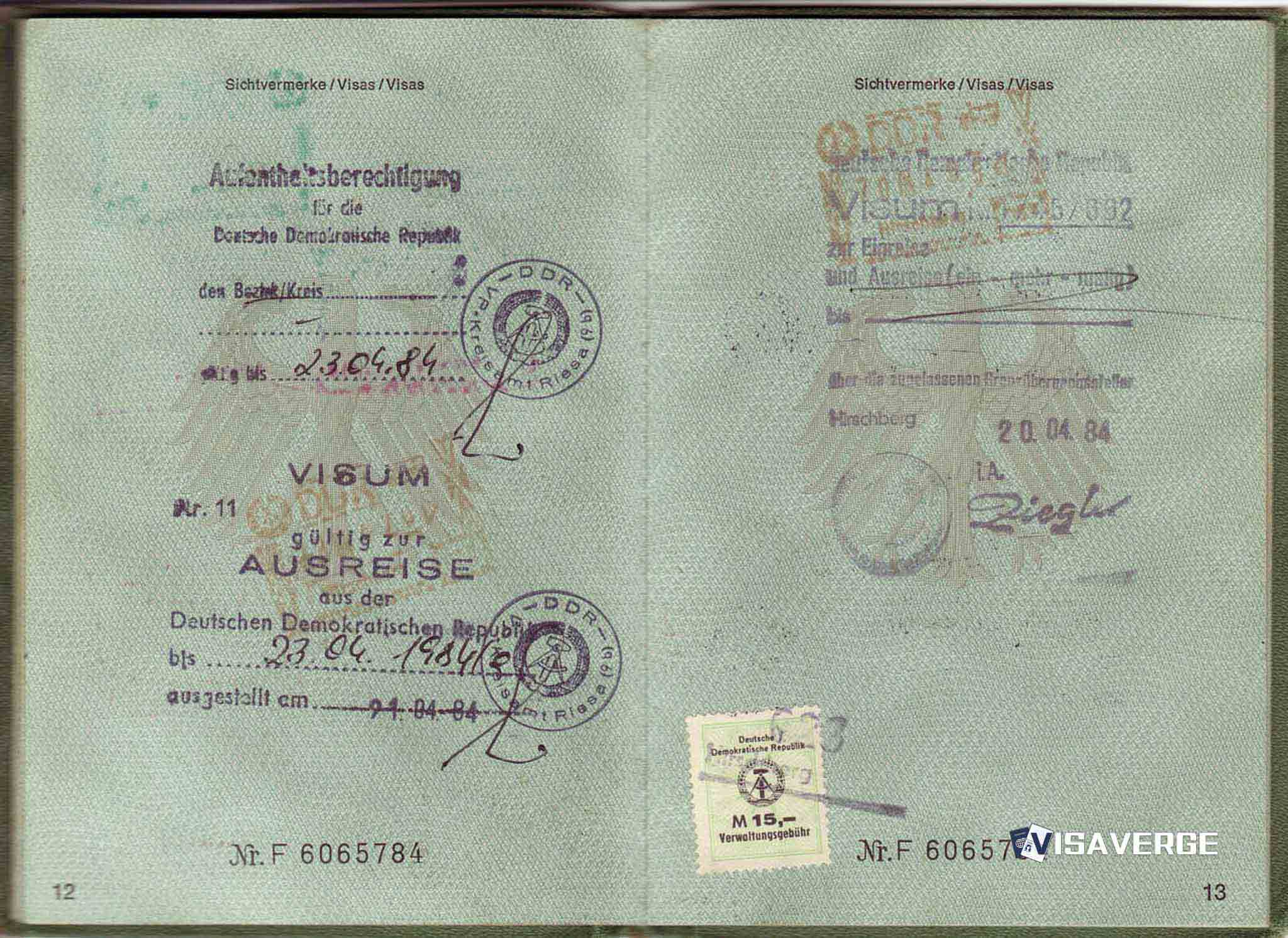

The reported refusal language, “migration risk,” commonly appears in short-stay visa decision-making as a rationale tied to an official’s concern that an applicant may not leave on time at the end of an authorized visit.

In practice, that concept typically turns on whether the applicant persuades a decision-maker that the trip has a clear purpose, a credible plan, and enough resources, and that the applicant has strong reasons to return to their country of residence.

Screen Daily’s account did not name the specific German authority that decided the case, and it did not set out the application dates.

The denials, as described in the report, drew attention to how cross-border cultural work can hinge on short-stay travel permissions, even when the underlying activity is time-limited and linked to a specific event.

Berlinale industry events operate on fixed schedules, and participation can be hard to reschedule once a market window closes, because meetings, pitches and introductions cluster around a limited set of days.

“Blue Card” came to the Co-Production Market with sales agent MAD World attached, Screen Daily reported.

In this market setting, a sales agent typically serves as the project’s commercial representative, helping shape the package presented to partners and using market access to set meetings and introductions that can affect financing, co-production interest and sales conversations.

Even when a film continues in development, missing a market can change the order and timing of negotiations, because buyers, funders and co-producers tend to make plans around festival calendars and the concentrated availability of decision-makers.

For filmmakers, the difference between arriving on day one and missing the market entirely can determine whether a project gets a first round of partner meetings or loses a year of momentum.

Short-stay visas across Europe’s Schengen area often rely on an applicant’s documents to show the purpose and conditions of travel, and refusal rationales can be phrased in standardized terms.

That standardization can make it difficult from public accounts to know what, if anything, turned on individualized facts in a specific application, beyond the basic refusal label.

Artists and film workers can face particular challenges in this framework because their work often runs project to project, their income can be irregular, and their travel may be frequent and tied to invitations rather than long-term employment contracts.

Creative work also tends to involve third-party funding structures, festival-hosted travel and short-notice schedule changes, all of which can complicate the kind of straightforward itinerary and financial documentation that short-stay decision-making often expects.

The case involving Alomda and Abu Alala emerged as the Berlinale drew international participants to Berlin for screenings and industry meetings, creating a high-pressure window in which late decisions or refusals can reshape who appears in the room.

Screen Daily framed the situation as a reminder of visa barriers facing artists from countries associated with higher migration pressures.

Alongside visa barriers, Berlinale 2026 also drew attention to access constraints that do not involve visas at all but can still force filmmakers to adjust how and where they work.

Screen Daily pointed to Afghan director Shahrbanoo Sadat filming in Germany due to Taliban restrictions.

That example represents a different type of constraint, but it leads to similar operational outcomes for filmmakers: changes to location, reduced freedom of movement, altered collaboration patterns and limits on visibility at major international gatherings.

Whether the barrier comes at a border, within a consular process, or from restrictions at home, the practical effect for a festival or market can be the same—projects and people cannot show up in the way they planned, and organizers and partners have to adapt.

For an industry market, the practical impacts often land on pitching, networking and dealmaking.

A project team that cannot travel may lose informal conversations that happen in hallways and dinners, and it may be forced to rely on intermediaries who can attend in person, which can change how a project is presented.

Official festival materials, meanwhile, typically reflect programming, scheduled events and juries rather than behind-the-scenes travel outcomes.

The official Berlinale program PDF lists juries and events but omits mention of the Sudanese project or withdrawals, Screen Daily reported.

As of February 14, 2026, Screen Daily reported no updates on visa appeals or the project’s participation status.

For practitioners, that kind of gap matters because it affects contingency planning, communications with partners, and decisions about whether to attempt remote participation or shift meetings to other settings.

In markets built around pre-arranged calendars, uncertainty can ripple into sponsor and partner relationships, because travel outcomes can dictate who can speak for the project and whether a pitch can happen at all.

The “Blue Card” episode also illustrates how visa uncertainty can touch multiple parts of a project’s financing path.

Co-production markets often function as a gateway to introductions with potential co-producers and financiers, and missing those meetings can affect timelines for assembling budgets, aligning schedules and securing commitments.

For international partners, a late-stage travel refusal can complicate legal and administrative planning as well, including who has authority to negotiate, who can sign in-person documents, and how meetings are documented.

Teams looking to reduce disruption often rely on practical measures that can be implemented without changing any government policy.

Those measures can include designating backup delegates who can travel, aligning early on who will represent the project if a key creator cannot attend, and preparing for remote meetings when in-person attendance fails.

Organizers and partners can also help by issuing clear invitation letters, confirming agendas and meeting schedules early, and providing usable points of contact for participants trying to match application requirements to specific market activities.

Flexibility in scheduling and the availability of remote meeting options can preserve some dealmaking even when travel falls through, though the loss of in-person access can still change outcomes.

Outcomes can vary from applicant to applicant and from consulate to consulate, even when the purpose of travel appears similar, because short-stay decision-making can turn on how an individual profile and documents fit a decision-maker’s expectations.

For filmmakers and their partners, the planning challenge is that the consequences of a refusal can be immediate, while the commercial and creative costs can unfold over months, as market opportunities move on.

In Berlin this year, Alomda and Abu Alala’s withdrawal from the Co-Production Market meant “Blue Card” could not proceed there as planned, leaving a selected project outside the room at one of the industry calendar’s most time-sensitive moments.