(TENNESSEE) — For immigrants facing stepped-up enforcement tied to “Immigration 2026,” the most immediate defense strategy is often a two-track plan: (1) protect liberty through bond and procedural challenges in immigration court, and (2) protect immigration benefits by preparing for USCIS “holds,” re-reviews, and follow-up evidence requests.

With Tennessee lawmakers promoting a state-level enforcement model developed in tandem with Stephen Miller, and parallel proposals moving through the House Judiciary Committee, defense planning now has to account for state bills, federal enforcement practices, and slower benefit adjudications.

This article explains the main defenses and relief options that typically matter most when enforcement increases: release from custody, suppression and due process motions, and core forms of relief (asylum, withholding, CAT, and cancellation). It also flags how benefit “holds” can affect work permits and health-related benefits decisions.

1. The “Immigration 2026” Package (State Level Model)

Tennessee’s “Immigration 2026” package is best understood as a coordinated set of state bills designed to test how far a state can push immigration enforcement while trying to survive court challenges.

Major bill themes in plain language

- A state “unlawful presence” offense. This aims to treat immigration status as a state criminal matter. That approach runs into federal supremacy concerns. The Supreme Court limited similar state criminal provisions in Arizona v. United States, 567 U.S. 387 (2012).

- Public-benefits verification mandates. These proposals typically require state and local agencies to verify lawful presence before providing taxpayer-funded benefits. In practice, that can affect access to certain state programs tied to healthcare, housing, and childcare administration.

- In-state tuition restrictions and school-tuition proposals. Measures that target undocumented students raise direct conflict issues with Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202 (1982), which held states cannot deny K-12 public education based on unlawful presence.

- 287(g) participation requirements. INA § 287(g) authorizes written agreements for state or local officers to perform certain immigration functions under federal supervision. Mandating participation can reshape local policing and jail screening.

- Penalties related to releasing immigration officers’ identifying information. These proposals can increase criminal exposure for officials and may affect how communities document enforcement actions.

Who could feel the effects

The practical impact can fall on undocumented residents, mixed-status families, students, employers, local law enforcement, and state agencies that administer benefits. It may also affect hospitals and clinics that help patients complete eligibility paperwork for state programs.

Why the preemption fight matters

Immigration is primarily federal. States still regulate criminal law, licensing, and benefits, but they cannot create their own immigration system. The legal battle usually turns on federal preemption, due process, and Equal Protection limits. States often add “trigger” clauses and narrower definitions to try to survive injunction requests.

Warning: State criminal charges can create immigration consequences. A plea that seems minor may trigger detention, removability, or bars to relief. Get immigration counsel before any criminal plea.

2. Federal Legislative Actions

At the federal level, the House Judiciary Committee has moved bills through markup that aim to accelerate removals, increase criminal penalties linked to border and asylum-related conduct, and pressure “sanctuary” jurisdictions through grant restrictions.

What a markup is, and why it matters

A committee “markup” is when members debate, amend, and vote on whether a bill should advance. Markup matters because it is where bill language hardens into a version that can reach the House floor. Even then, House passage alone does not make a bill law. Senate action and the President’s signature are required.

Real-world effects if proposals become law

- Bills described as “supercharging” removals commonly seek to:

- Expand mandatory detention or criminal penalties.

- Narrow discretionary release tools.

- Increase penalties tied to reentry and certain border-related conduct.

- Condition federal grants on compliance with federal immigration cooperation requests.

ICE detainers and local cooperation

ICE detainers are requests that local agencies hold a person for up to 48 hours beyond their release time, excluding weekends and holidays. The main regulation is 8 C.F.R. § 287.7. Jurisdictions disagree because detainers are generally treated as requests, not judicial warrants, and local agencies weigh liability and community trust concerns.

3. Official DHS and USCIS Statements (Direct Quotes)

Defense strategy becomes more concrete when grounded in what agencies say they are doing.

Administrative warrants versus judicial warrants

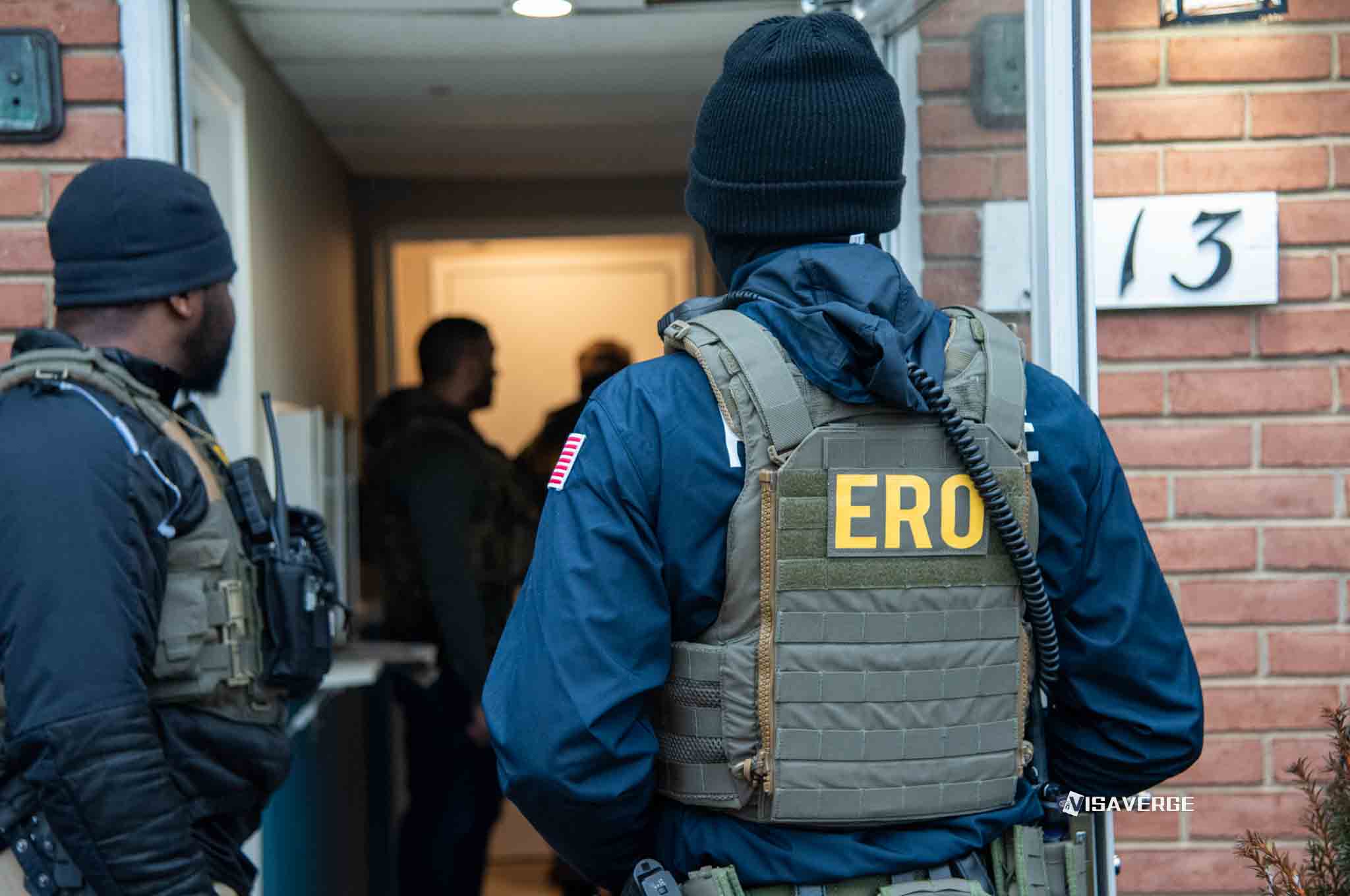

DHS has publicly defended the use of administrative warrants in immigration arrests. On February 4, 2026, DHS stated:

“There is broad judicial recognition that illegal aliens aren’t entitled to the same Fourth Amendment protections as U.S. citizens. While administrative warrants may satisfy the Fourth Amendment for any arrest of an illegal alien, ICE currently uses these warrants to enter an illegal alien’s residence only when the alien has received a final order of removal from an Immigration Judge.”

Administrative warrants (often on Forms I-200 or I-205) are issued within DHS, not by a neutral judge. A judicial warrant is signed by a judge. In many jurisdictions, whether and when officers can enter a home without judicial authorization can be heavily fact-specific, and circuit law may differ. That is why counsel may examine the arrest location, consent issues, and paperwork.

DHS has also defended masking practices as officer-safety measures, while critics allege intimidation or retaliation. Those disputes can become relevant in suppression motions, civil-rights litigation, and public-records battles, depending on facts.

USCIS “hold” and “re-review” for certain nationals

USCIS has also described a benefit “hold” policy that can affect pending cases and work permits. The relevant policy memo identifier is USCIS Policy Memo 26-001 (Jan. 1, 2026). The memo describes:

- A “hold” on pending benefit requests for nationals of 75 identified “high-risk countries.”

- A “re-review” of already approved cases for nationals of 39 “primary” countries since January 20, 2021.

A “hold” generally means processing pauses while additional screening occurs. A re-review can lead to follow-up actions such as Requests for Evidence (RFEs) or Notices of Intent to Deny (NOIDs). This can affect employment authorization timing and, indirectly, access to employer-sponsored health coverage.

For procedural background, USCIS guidance is consolidated in the USCIS Policy Manual.

Deadline watch: RFEs and NOIDs have firm response deadlines. Missing a deadline can lead to denial, even when underlying eligibility exists.

4. Statistics and Policy Impact

Reports of higher daily arrest targets can change field behavior. Even without new statutes, increased operational tempo can mean:

- More workplace and community operations.

- Higher detention volume.

- Faster initiation of removal proceedings.

- Greater pressure to accept quick dispositions.

Large metro operations can also strain community relations and increase scrutiny after high-profile incidents. When operations draw public attention, defense counsel often responds by seeking records, challenging arrest practices, and pressing for bond hearings.

Shutdown mechanics and why enforcement can continue

A partial shutdown can reduce some administrative processing, but enforcement operations may continue if funded through multi-year appropriations or special funding “cushions.” In that environment, benefits adjudications may slow, even as removals accelerate. That mismatch increases the need for fast, well-documented filings and attorney-coordinated case triage.

5. Significance and Context: What to monitor, and how to plan defenses

Tennessee-style models are often used as test cases to tee up major preemption disputes. If multiple states adopt similar provisions, the conflicts can reach circuit courts and potentially the Supreme Court.

Political strategy can also shape pacing. Internal party critiques may influence messaging, but enacted statutory text is what controls. For defense planning, the most important signals are practical and documentable:

- Whether a bill is enacted, and its final wording.

- Whether courts issue temporary restraining orders or preliminary injunctions.

- Whether DHS and USCIS publish implementation guidance that changes procedures.

- Whether local sheriffs sign 287(g) agreements or expand jail screening.

Core defense tools in removal cases

- Bond and custody review (release planning). Many noncitizens may seek bond under INA § 236(a). Mandatory detention issues can arise under INA § 236(c). Bond factors can include flight risk, danger, family ties, and past compliance. See Matter of Guerra, 24 I&N Dec. 37 (BIA 2006).

- Suppression and termination motions. Where facts support it, counsel may seek suppression of unlawfully obtained evidence or termination for egregious violations. Success varies by circuit and facts.

- Applications for relief. Depending on the case, relief may include asylum (INA § 208), withholding (INA § 241(b)(3)), CAT protection, or cancellation of removal (INA § 240A). Each has distinct burdens, bars, and evidentiary needs.

Evidence that typically strengthens cases

- Identity documents and proof of continuous residence.

- Medical records and proof of caregiving, when relevant to hardship.

- Tax records and employment history, showing stability and equities.

- School records for children and special education documentation.

- Police reports and certified dispositions, if any arrests exist.

- Country-condition evidence for fear-based claims.

Common case-weakening factors and bars

- Certain criminal convictions can trigger mandatory detention, removability, or bars. The analysis is statute-specific and complex.

- Prior removal orders and unlawful reentry can sharply limit options and increase detention risk.

- Misrepresentation findings can bar relief in some categories.

- Failure to appear for hearings can lead to in absentia orders, with strict reopening rules.

Warning: Do not sign stipulated removals, “voluntary return” paperwork, or agreed deportation orders without legal review. These decisions can cut off future relief.

Outcome expectations

There is no single win-rate that applies across jurisdictions. Outcomes vary by judge, circuit, custody posture, and evidence quality. What is realistic is that attorney-led preparation usually improves issue spotting, filing compliance, and record building for appeal.

Why attorney representation is critical right now

The overlap of state enforcement experiments, federal legislative proposals, aggressive detention posture, and USCIS holds makes self-representation unusually risky. Small errors can trigger missed deadlines, unnecessary detention, or permanent bars. If you are detained or served with an NTA, rapid consultation can be decisive for preserving relief.

Legal resources (official and referrals)

- EOIR Immigration Court info: justice.gov/eoir

- USCIS Policy Manual: uscis.gov/policy-manual

- AILA Lawyer Referral: aila.org/find-a-lawyer

⚖️ Legal Disclaimer: This article provides general information about immigration law and is not legal advice. Immigration cases are highly fact-specific, and laws vary by jurisdiction. Consult a qualified immigration attorney for advice about your specific situation.