1) What Matter of G-M-I- changed about expert testimony in immigration court

A new BIA ruling clarifies that judges must independently evaluate expert evidence in removal cases, striking down deferential treatment to experts and shaping how CAT, asylum, and country-condition claims are litigated. In Matter of G-M-I-, 29 I&N Dec. 431 (BIA 2026), the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) held that Immigration Judges (IJs) must decide the probative weight of an expert witness opinion for themselves. No automatic deference applies just because a witness has credentials.

Three terms drive the decision.

Probative weight means how persuasive a piece of evidence is on a disputed point. The IJ decides how much the evidence actually proves.

Factual basis means the concrete facts an opinion rests on. Those facts should be in the record and should match the respondent’s situation.

Legal conclusion means an opinion that answers the legal question the IJ must decide. Examples include whether the respondent “meets the CAT standard” or whether feared harm “counts as torture” under the legal definition.

Matter of G-M-I- does not ban expert reports. It narrows what they can do. Expert testimony may explain specialized topics beyond common knowledge, but it cannot replace missing record facts. The decision also sets out a practical logic for assessing expert evidence, which many practitioners will recognize as a series of threshold questions about qualifications, foundation, and fit.

2) Key holdings on expert witness evidence (and how they tie to earlier BIA precedent)

Matter of G-M-I- treats expert testimony like other evidence in removal proceedings. The expert’s resume does not decide the case. The IJ does.

Several holdings matter in day-to-day litigation:

Expert evidence is not a substitute for the IJ’s factfinding. The BIA emphasized that IJs are the triers of fact in immigration court. That role includes deciding what to credit, what to discount, and what carries limited probative weight.

Generalized predictions are a red flag when they stand in for case-specific facts. The BIA criticized “predictive inferences” drawn from broad materials when they effectively “establish” facts that were not shown for the particular respondent. Put plainly, an expert cannot bridge a missing link by guessing that what happens to some people will happen to this person.

A sufficient factual basis must be tied to the respondent’s circumstances. Credentials alone are not enough. The opinion should show why the expert’s sources, comparisons, and reasoning match the respondent’s profile and risk factors.

Experts should not opine on the ultimate legal issues. An expert can describe detention conditions, interrogation methods, or state practices. The IJ must decide whether that conduct meets the legal standard for torture, acquiescence, or a protected-ground nexus.

Two earlier BIA decisions reinforce this approach without changing the core point. Matter of M-A-M-Z-, 28 I&N Dec. 173 (BIA 2020) and Matter of J-G-T-, 28 I&N Dec. 94 (BIA 2020) both reflect the same discipline: expert opinions can help, but they do not control, and generalized reasoning cannot be used to reach case-determining findings without a solid foundation.

For practitioners, the checklist-style decision tree that often appears in training materials is now anchored by a published standard. It boils down to qualification, foundation, fit, and scope. If any step fails, probative weight typically drops.

Table 1: How the BIA treats expert testimony versus other evidence under G-M-I-

| Evidence Type | Judicial Treatment | Key Limitation | Impact on CAT/Protection Claims |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expert report / affidavit | Considered like any other exhibit; IJ assigns probative weight | Must show specialized knowledge and a sufficient factual basis tied to the respondent | Weak foundation can sink “likelihood” showings under CAT and reduce value for country-conditions linking |

| Expert live testimony | IJ evaluates credibility and persuasiveness, including methodology | Should not answer ultimate legal questions | Overreach into legal conclusions can lead to discounting or reversal on appeal |

| Country-conditions reports (government/NGO) | Background evidence; helps establish general conditions | Often too general to prove individualized risk alone | Usually needs linking evidence (personal history, targeting factors) for CAT/asylum |

| Respondent declaration and supporting witnesses | Direct factual evidence; IJ weighs consistency and detail | Must be internally consistent and corroborated where available | Provides the individualized facts experts must build on |

| Criminal and detention records | Objective documentation; often carries strong weight | May be incomplete or ambiguous without context | Can shape risk analysis, especially where return consequences depend on conviction type |

[!warning] ⚠️ Important: Expert opinions must be grounded in case-specific facts and not treated as substitutes for material record evidence

3) How the BIA applied the framework to the CAT claim

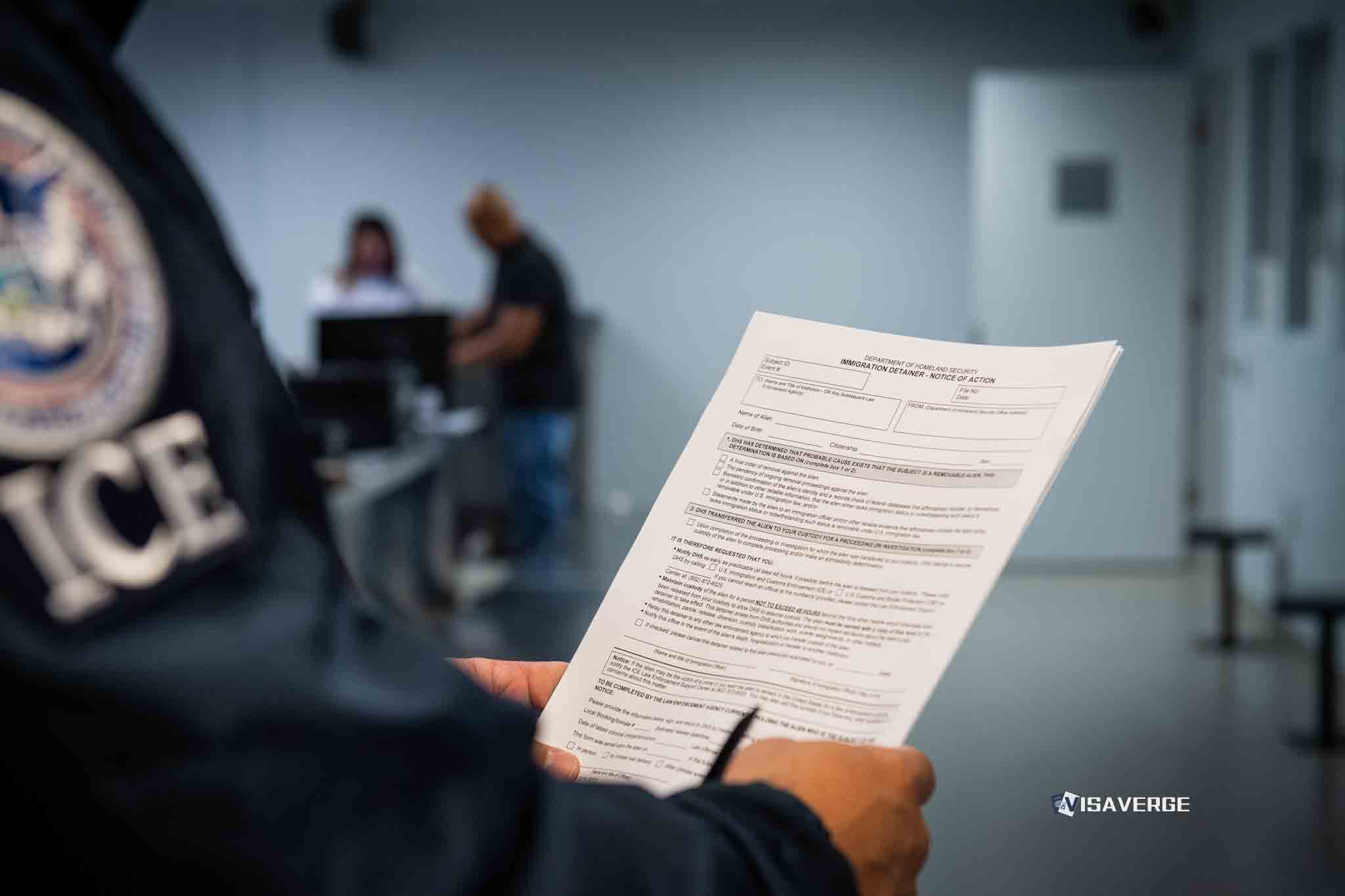

Matter of G-M-I- arose from a protection grant that turned heavily on expert evidence. An IJ decision dated March 26, 2025 granted CAT deferral of removal to a respondent from the People’s Republic of China who had a drug trafficking conviction in the United States. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) appealed.

CAT deferral has a demanding core requirement. The respondent must show that torture is more likely than not if removed. That “likelihood” analysis typically turns on both general country conditions and individualized risk factors.

On appeal, the BIA conducted de novo review of the CAT determination described in the decision. De novo review means the BIA does not accept the IJ’s conclusions as a given on the reviewed issues. It evaluates the question anew under the governing standard.

The expert opinion was central to the IJ’s ruling, yet the BIA found it flawed in ways that mattered for burden of proof. The BIA faulted the expert for lacking direct knowledge tied to the relevant scenario and for relying on non-analogous examples. The opinion also failed to address dissimilar circumstances between cited materials and the respondent’s situation. Once that testimony lost probative weight, the remaining record did not establish the required likelihood of torture.

One lesson is procedural but practical. When an IJ’s CAT outcome rests on an expert’s broad prediction, the appeal may focus less on the expert’s credentials and more on the opinion’s factual basis and fit.

4) What changes in practice for removal cases involving experts

Country-conditions experts, medical and psychological experts, and security specialists appear often in protection claims. Matter of G-M-I- makes the “linking” work harder. Broad descriptions of repression or harsh detention conditions may remain relevant, yet they must connect to the respondent’s own risk factors.

Respondents are likely to feel this most in CAT litigation. The standard is individualized and probabilistic. Experts may describe how authorities treat certain categories of returnees, but the opinion should show why the respondent fits that category and why the comparison is sound.

DHS may also adjust how it challenges expert evidence. Attacks may focus on foundation, methodology, and scope rather than credentials alone. Cross-examination can press on what the expert personally knows, what sources were used, and whether the sources truly match the respondent’s profile.

IJs, for their part, are expected to separate three things: (1) specialized factual explanations, (2) forward-looking factual predictions supported by case-specific facts, and (3) legal conclusions that belong to the court. That separation can affect federal court review at a high level, because appellate courts often defer to agency factfinding when the agency explains how it weighed evidence.

USCIS does not run removal court, but the ripple can reach agency practice. BIA standards may guide how DHS frames appeals and how government attorneys evaluate expert materials. The same discipline can influence how evidence is assessed in related contexts, including when records developed before USCIS later appear in removal proceedings.

5) Regulatory context and procedural timing: why deadlines now matter more

Procedural timing has become tighter. An interim final rule issued February 6, 2026 and effective March 9, 2026 restructures parts of the BIA appeals process. In practice, that kind of change can affect where disputes about expert evidence get resolved and how quickly parties must act.

Shortened filing windows raise the stakes for preserving expert-evidence issues early. The policy update materials tied to this rule highlight a 10-day figure, which signals that some appeal-related deadlines may be compressed. Missing a deadline can forfeit review options, even when the evidentiary issue is strong.

Expert disputes also present a strategic fork. Some issues may be framed for BIA review, while others may later be raised in a petition for review. Parties typically benefit from building a clear record either way, because evidentiary weight questions often turn on what the IJ actually found and why.

For official background on immigration adjudication and appeals, readers can consult the Department of Justice’s Executive Office for Immigration Review resources at justice.gov.

6) Guidance for practitioners and respondents after G-M-I-

Expert testimony still has a real role. Many IJs welcome help on specialized subjects, especially where the record needs technical explanation. The post-G-M-I- risk is not the use of experts. The risk is using them as a shortcut.

- Speculation framed as certainty.

- Generalized assertions that do not match the respondent’s attributes or history.

- Legal conclusions that tell the IJ how to rule.

- Thin foundations, where key underlying facts never entered the record.

Record-building becomes the hinge. If an expert relies on a past arrest, political activity, medical condition, or prior threats, those facts should be supported by declarations, documents, or credible testimony. Otherwise, the IJ may treat the opinion as floating above the record.

Issue preservation also matters. When DHS challenges foundation or scope, counsel may need to respond with record citations, clarifying testimony, or revised reports where permitted. When the respondent believes the IJ discounted an expert improperly, the objection should be clear and tied to the standard the IJ was required to apply.

[!action] ✅ For practitioners: ensure expert reports connect methodology and findings to the respondent’s circumstances and disclose factual bases

A careful expert report does not promise an outcome. It does something more defensible. It shows its work, anchors opinions to record facts, and leaves legal conclusions to the court.

This article discusses legal standards and should not be construed as legal advice.

Readers should consult an attorney for case-specific guidance and consider jurisdictional differences.