(AURORA, COLORADO) More people held at the Aurora ICE facility are agreeing to leave the United States 🇺🇸 through Voluntary departure, according to advocates and attorneys who track detention trends. As of October 22, 2025, there is limited facility-specific data on exactly how many detainees have taken this route. Still, available context points to a mix of pressure inside detention, national policy shifts, and rising custody numbers that may be pushing more detainees toward a faster exit rather than fighting their cases from inside the Denver Contract Detention Facility in Aurora.

Voluntary departure is when a person agrees to return to their home country without a removal order. It’s a legal option, not a deportation order, and it usually means a quicker release from custody. Reports indicate that people who accept voluntary departure spend the fewest days in detention—an average of about 4 days, with about 90% released within the first three days.

For detainees stuck far from family, work, and medical care, the pull of a quick release can be strong, especially when the alternative is months in detention while a court case slowly moves forward.

Conditions and context inside Aurora

The Aurora ICE facility, operated by GEO Group, has faced steady criticism. People formerly held there have reported sparse meals, undrinkable water, and abusive language from guards. Even when ICE disputes these accounts, such reports can weigh on detainees’ decisions.

When someone weighs a short stay and a flight home against weeks or months inside a facility where they feel unsafe or unwell, the calculation often changes.

Advocates also point to broader policy changes that have expanded mandatory detention for certain categories of immigrants. This shift can mean longer waits and fewer chances to be released on bond. When detention seems open-ended, the appeal of voluntary departure grows.

That pressure is not theoretical. As of June 2025, ICE was holding a record number of people in detention nationwide. More people in custody means more delays—medical visits, court dates, attorney meetings—everything takes longer. For many detainees, time is the most valuable thing they have. Voluntary departure offers a way to get some control back.

At the same time, Colorado leaders have raised concerns about what’s happening inside Aurora. Senator John Hickenlooper has questioned transparency and accountability at the facility, including reports of ICE staff pressuring detainees to self-deport. If even some detained people feel pushed toward this choice—rather than making it freely—that raises legal and ethical questions. The law allows voluntary departure as a choice. It should not be the result of fear or coercion.

How voluntary departure affects people

According to analysis by VisaVerge.com, voluntary departure can sometimes shorten detention compared to fighting a case from custody. Yet it carries lasting consequences:

- A person must leave the country, often at their own expense.

- They may face bars to reentry for a period under immigration law.

- For some, it’s a strategic pause—leave now, regroup with family, and explore legal options from abroad.

- For others, it feels like giving up on a life built over years in the United States 🇺🇸.

“Voluntary departure offers speed, but not without cost.” — key takeaway from advocates and legal analysts

What’s driving more voluntary departures

- Detention conditions in Aurora: Reports of poor food, water problems, and verbal abuse make detention feel harsher and less bearable. The possibility of harm or humiliation can tip the balance toward leaving.

- Policy shifts expanding mandatory detention: When the law requires detention for more people, release options narrow and the risk of long detention increases.

- Record detention numbers: With ICE holding more people, everything slows down; longer waits mean mounting stress, higher legal costs, and a deeper sense of uncertainty.

- Concerns over pressure to “self-deport”: Oversight by Senator Hickenlooper highlights worries that some detainees may not feel free to choose. That perception can spread across the facility and affect decision-making.

Voluntary departure isn’t the right path for everyone. People with strong asylum claims or other defenses may be better off seeing their cases through—especially if they have legal help and a reasonable path to relief. But for those who prefer to avoid a removal order and want out of detention quickly, it can be a practical option.

Practical steps and support for detainees

For detainees thinking about voluntary departure, several steps can prevent mistakes and protect future options:

- Legal consultation first

- Speak with a lawyer or accredited representative before agreeing to anything.

- A short conversation can clarify rights, timelines, and the impact on future travel or visas.

- If cost is a barrier, ask for a free legal orientation or a pro bono referral list inside the facility.

- Ask questions in plain language

- If an officer discusses voluntary departure, ask:

- Will I get a removal order?

- How soon will I be released?

- What costs will I pay?

- When will I fly?

- Get answers in writing if possible.

- If an officer discusses voluntary departure, ask:

- Family coordination

- Tell family right away so they can plan for travel, pick-up, and funds.

- Leaving the country without warning can cut off contact and support at a critical moment.

- Document return of property

- Ensure IDs, phones, money, and personal items are tracked and returned at release.

- Keep receipts and copies.

- Post-release help

- Local groups can bridge the gap between release and home.

- Examples:

- Casa de Paz in Aurora — helps people leaving detention with rides, short-term shelter, meals, and phone access.

- Colorado Immigrant Rights Coalition (CIRC) — monitors conditions and connects families with legal and social services.

For official guidance on the legal basics of this option, the Department of Justice’s Executive Office for Immigration Review explains how voluntary departure works and who may qualify. See: EOIR guidance on voluntary departure. This is a government resource that outlines the rules, timelines, and eligibility factors.

Speed, consent, and oversight

The process inside Aurora can move quickly once a person agrees. That speed is part of the appeal, but it also means decisions often happen under stress. The most important safeguard is informed consent—saying yes only after learning the consequences and alternatives.

If someone feels pressured, they can:

– Ask to speak with a supervisor

– Request a legal call

– File a written complaint

Keeping notes of dates, names, and conversations can help if any issues arise later.

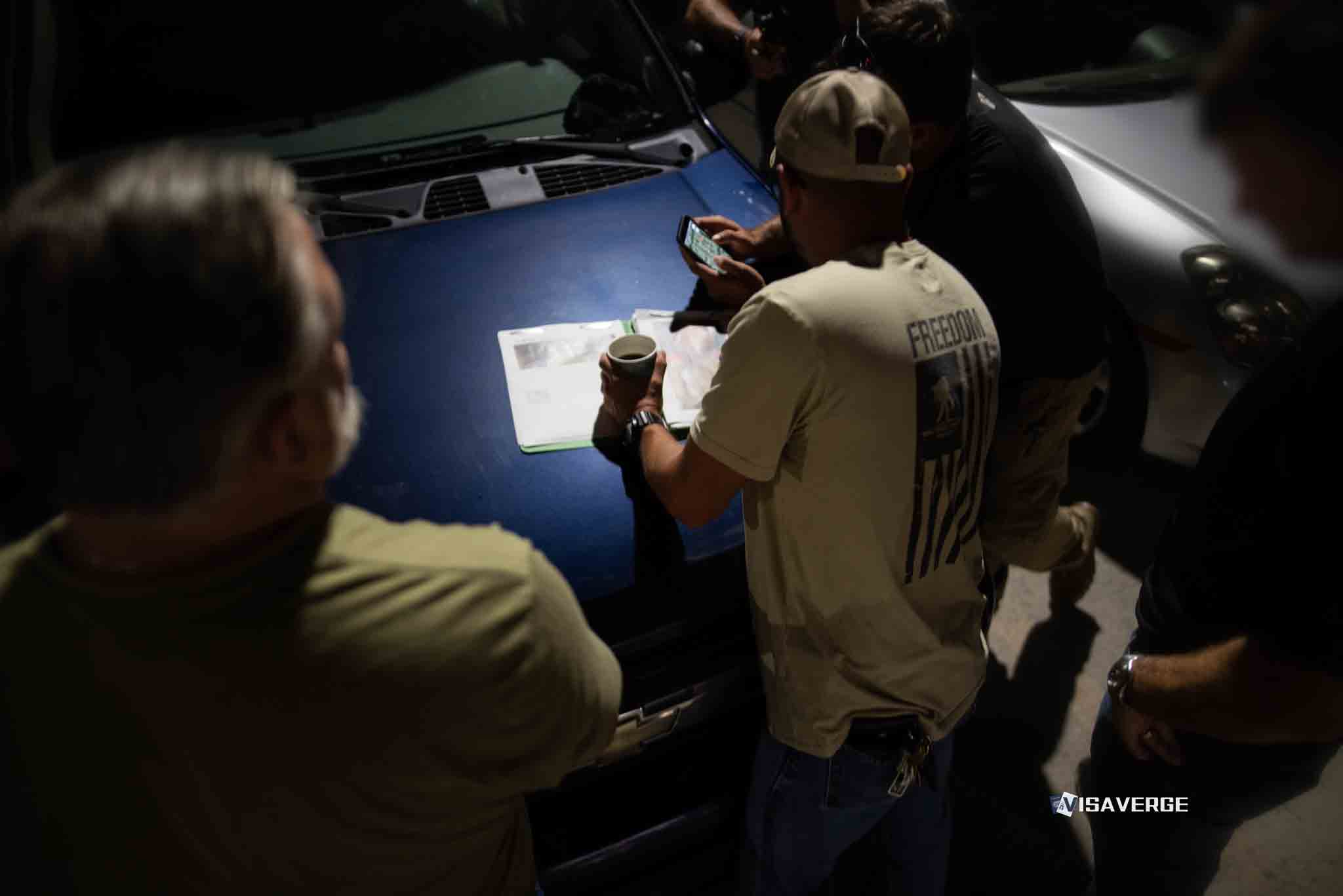

Advocacy groups say more transparency from ICE would help the public judge what is happening at the Aurora ICE facility. Clear data on how many people accept voluntary departure, how long they are detained before release, and whether anyone reports pressure to agree would allow voters, families, and lawmakers to assess conditions and outcomes. ICE regularly publishes national detention numbers, but drilling down to facility-level trends remains hard without public records requests or court filings.

The human stakes

The choices detainees face are deeply personal and consequential:

- A father who chooses voluntary departure may reunite with parents abroad within days, but he may leave a spouse and children behind in Colorado.

- A young asylum seeker may avoid a removal order now, yet face danger when they return to their home country.

Each choice carries weight. Each person must balance risk, time, and safety.

For those seeking more help, families can:

– Contact local nonprofits

– Ask attorneys about bond or parole possibilities

– Request written information from facility staff

And for detainees, one rule holds: don’t sign anything you don’t understand. Even a fast exit deserves a careful decision.

This Article in a Nutshell

Advocates and attorneys tracking detention trends report an uptick in detainees at the Aurora ICE facility choosing voluntary departure — a legal option permitting return to a home country without a removal order. Facility-specific data is limited, but available information suggests poor conditions, policy shifts expanding mandatory detention, and record national custody levels (as of June 2025) are contributing factors. Those who opt for voluntary departure typically spend roughly four days in custody, with about 90% released within three days. Legal consultation, family coordination, and documentation of property and conversations are recommended. Community organizations such as Casa de Paz and CIRC offer post-release assistance. Oversight concerns raised by Colorado leaders, including Senator John Hickenlooper, highlight worries about potential pressure on detainees and call for greater transparency and data on facility-level trends.