Taxpayers planning education gifts for children and relatives in the United States face a sharp divide in federal gift tax treatment this year: gifts of future interests still don’t qualify for the annual exclusion and must be reported, while contributions to a Qualified Tuition Program (like a 529 Plan) continue to be treated as present interest gifts that can use a helpful five‑year “front‑loading” election. The distinction matters for families — including many immigrants building long‑term support plans for students — because the wrong structure can force a gift tax filing even when no tax is due.

Key concept: present interest vs. future interest

- The central rule is the annual exclusion: the amount a person can give to each recipient each year without tapping lifetime gift allowances or triggering filing in many situations.

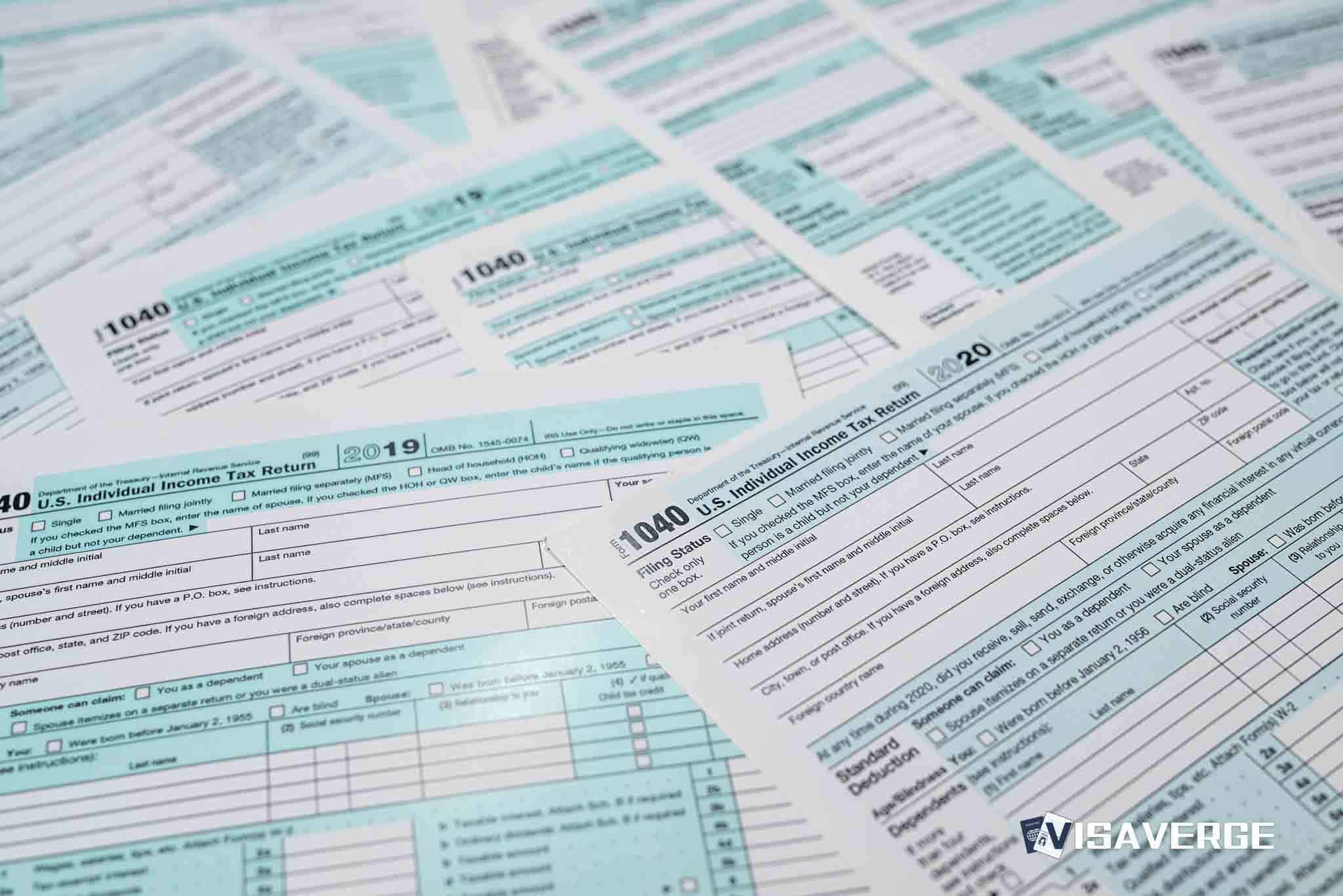

- Under federal law, a gift of a future interest doesn’t qualify for the annual exclusion and must be reported on the IRS gift tax return

Form 709, regardless of the gift’s amount. - The defining test is timing: if the recipient cannot use, possess, or enjoy the gift right away, it’s a future interest. Common examples include transfers into trusts where a child cannot access funds until a later date.

- By contrast, a direct contribution to a Qualified Tuition Program (529 Plan) is treated as a present interest because the beneficiary has an immediate, current benefit tied to education. That difference allows the annual exclusion to apply.

Important takeaway: the timing of enjoyment/use determines whether the gift qualifies for the annual exclusion.

529 Plans and the five‑year front‑loading election

Contributions to a Qualified Tuition Program (529 Plan) include a powerful planning feature: donors can elect to spread a single large gift over five years for gift‑tax purposes (often called front‑loading).

- In 2024:

- Single donor front‑loading limit: $90,000 (five times the $18,000 annual exclusion).

- Married couple (gift splitting): $180,000 per beneficiary.

- In 2025 (figures provided):

- Single donor front‑loading limit: $95,000 (five times the $19,000 annual exclusion).

- Married couple (gift splitting): $190,000 per beneficiary.

How the election works:

1. Donor makes a single 529 contribution in Year 1.

2. Donor elects to treat that contribution as made ratably over five years, starting in Year 1.

3. Each year of the five‑year period, the portion of the contribution counts against the annual exclusion for that year.

Practical notes:

– Many families time contributions (parents, grandparents) so a single deposit covers multiple semesters while still fitting under the annual exclusion via the five‑year election.

– Some donors avoid making other gifts to the same beneficiary during the five‑year span to prevent use of additional annual exclusion amounts that could complicate the election.

Strict rule for future interests and reporting

- The general rule remains strict: no annual exclusion is allowed for future interests.

- Even small future‑interest gifts must be reported on

Form 709. - Planners sometimes attempt to convert a future interest into a present interest using short, immediate withdrawal rights (e.g., “Crummey” powers), but the withdrawal right must be real and meaningful. If not, the gift is still treated as a future interest and is reportable.

Filing and documentation

- When a gift is a future interest, or when a donor makes a five‑year 529 election, the reporting document is

Form 709, United States Gift (and Generation‑Skipping Transfer) Tax Return. - Official IRS page for this form (instructions and updates): Form 709

- Keep clear records of:

- Contribution date

- Beneficiary identity

- Any gift‑splitting decision between spouses

- The five‑year election choice (if used)

Even when no gift tax is due, accurate filing and recordkeeping help prevent future questions—especially for families who plan to make additional gifts later.

Policy numbers, lifetime exemption, and examples

- Lifetime gift and estate tax exemption (provided figures):

- $13.61 million for 2024

- $13.99 million for 2025

While the lifetime exemption underlies larger estate planning, day‑to‑day education funding often focuses on the annual exclusion and the 529 five‑year election.

Example scenario:

– A grandparent contributes $90,000 to a 529 Plan in 2024 and elects the five‑year spread.

– Each year from 2024 through 2028, $18,000 of the annual exclusion applies to that beneficiary.

– If a married couple uses gift splitting, they can contribute $180,000 in 2024 with the same election.

– If instead the money goes into a trust where the child can’t access funds until age 21, it’s a future interest — no annual exclusion and a mandatory Form 709 filing.

Practical considerations for immigrant and mixed‑family situations

- For immigrant families settled in the U.S. and intending to set aside funds for a child’s schooling:

- A contribution to a Qualified Tuition Program is treated as a completed present interest gift to the beneficiary.

- 529 Plans are therefore a flexible, tax‑efficient way to support education while staying within the annual exclusion.

- The five‑year election lets relatives (including those abroad) put larger sums to work early without immediate gift tax consequences if a U.S.‑based relative executes the donation strategically.

Design traps and Crummey powers

- Some families ask whether a trust can be drafted to avoid the future‑interest problem.

- Techniques such as “Crummey” powers can convert a future interest into a present interest if they grant the beneficiary a genuine, immediate withdrawal right for a short window.

- These designs are exacting: if the withdrawal right isn’t real, the gift remains a future interest and must be reported.

Final practical checklist

- Decide whether the gift gives the beneficiary a present right (can use/enjoy now) or is a future interest.

- Confirm the current annual exclusion amount for the year of the gift.

- Document any five‑year 529 election and retain supporting records.

- If the gift is a future interest, prepare to file

Form 709. - If using a 529 Plan, consider front‑loading within the year’s limits and decide whether spouses will elect gift splitting.

The rules can feel technical, but they draw a bright line: if the recipient can enjoy the gift now, the annual exclusion can apply; if enjoyment starts later, the gift is reportable. The Qualified Tuition Program rule and the five‑year front‑loading option give families a clear, practical path to fund education while managing federal gift tax reporting and limits.

This Article in a Nutshell

Federal gift tax rules draw a clear line between present and future interests. Gifts that beneficiaries cannot immediately use are future interests, do not qualify for the annual exclusion, and must be reported on Form 709 even if no tax is due. In contrast, direct contributions to Qualified Tuition Programs (529 Plans) qualify as present-interest gifts and can use a five-year front-loading election, letting donors spread a large contribution across five years for annual-exclusion purposes. For 2024 the front-loading limits are $90,000 for single donors and $180,000 for married couples; 2025 projections rise to $95,000 and $190,000. Families, including immigrant households, should document contributions, consider gift-splitting, and maintain records. Estate-tax lifetime exemptions (about $13.61M in 2024 and $13.99M in 2025) remain separate but inform broader planning. Trusts can work if Crummey powers provide meaningful immediate withdrawal rights; otherwise transfers remain reportable as future interests.