Around 250 federal border agents are set to flood into New Orleans in the coming weeks as part of a two‑month immigration crackdown called “Swamp Sweep”, a major operation that aims to arrest about 5,000 people across southeast Louisiana and into Mississippi. The deployment, expected to begin in earnest on December 1, will turn multicultural New Orleans into one of the most closely watched testing grounds for President Trump’s promise of mass deportations.

Agents are scheduled to start arriving in the city on Friday, November 21, to stage vehicles and equipment before the Thanksgiving holiday, according to planning documents reviewed by the Associated Press. They are then expected to return toward the end of the month, with the full Swamp Sweep launch in early December.

Teams from the U.S. Border Patrol are preparing to spread out across neighborhoods and business areas stretching from central New Orleans through Jefferson, St. Bernard and St. Tammany parishes, and as far north as Baton Rouge, with more activity planned in southeastern Mississippi. The scale of the operation, and the choice of southeast Louisiana as a target, signal that the administration sees this region as a high priority in its broader immigration strategy.

Leadership and planning

Gregory Bovino, the Border Patrol commander chosen to run Swamp Sweep, has built a reputation inside the Trump administration as the preferred designer of large‑scale raids and arrests. His past role in similar operations has drawn sharp criticism from civil rights groups, and his presence in New Orleans is viewed by many advocates as a sign that officers will push hard during the crackdown.

To support such a wide push, federal agencies are building what amounts to a temporary enforcement hub across the New Orleans area:

- A portion of the FBI’s New Orleans field office has been set aside as a command post where leaders can coordinate movements and process arrests.

- A nearby naval base about five miles south of the city will hold vehicles, gear and thousands of pounds of so‑called “less lethal” munitions, including tear gas and pepper balls.

- Homeland Security has asked to use the Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base New Orleans for up to 90 days starting this weekend, suggesting the operation could keep a large footprint even beyond the initial two‑month window.

New Orleans demographics and community context

New Orleans, home to about 357,767 residents as of 2025, has long marketed itself as a city built on many cultures, and that reality shapes local reactions to Swamp Sweep.

Key population figures (2025):

| Group | Percent |

|---|---|

| Black or African American | 55.2% |

| White | 31.6% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 8.0% |

| Asian | 2.8% |

- The Hispanic community has grown sharply since Hurricane Katrina, rising from 3% in 2000 to 8% in 2025, largely because immigrant workers came to rebuild homes, hotels and roads and then stayed.

- For many immigrant workers and their families, the idea of hundreds of federal agents moving through their neighborhoods has stirred deep fear.

“There is a lot of fear in my city,” said Mayor‑elect Helena Moreno, who is herself a Mexican‑American immigrant and the first Latina to lead the city. She added she is racing to make sure people who may be targeted know their rights if they are stopped or questioned.

“I’m very concerned about due process being violated, I’m very concerned about racial profiling,” Moreno said. She takes office on January 12, meaning most of Swamp Sweep will unfold as she transitions into power.

City, state and federal tensions

While city leaders speak about protecting community trust, state officials have taken a sharply different path.

Governor Jeff Landry has worked to pull New Orleans into closer cooperation with federal immigration enforcement, backing new state laws and legal fights that pressure local agencies to assist with arrests and detention. Key state actions include:

- A law threatening jail time for local law enforcement officials who delay or refuse to carry out federal immigration requests.

- A statute ordering state agencies to verify, track and report anyone in the United States 🇺🇸 without legal status who receives state services.

- A measure that blocks city rules preventing cooperation with federal immigration agencies.

Those laws now collide with a complicated local history. For years, both the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office and the New Orleans Police Department (NOPD) have operated under federal oversight agreements that specifically barred them from carrying out immigration enforcement. That oversight for NOPD ended on Wednesday, leaving a gray zone that worries local monitors.

Stella Cziment, the city’s Independent Police Monitor, warned officers may face confusing signals as Swamp Sweep ramps up and state and city leaders send different messages about how far the police should go.

New Orleans Police Chief Anne Kirkpatrick has tried to calm some concern, saying existing NOPD policies that keep officers out of immigration enforcement “are not in conflict” with the new state laws. Mayor‑elect Moreno has also stressed that city police will follow state law while still treating immigration enforcement as a civil matter that lies outside their main duties.

This balance reflects a wider national tension over how much local police should participate in immigration operations led by federal agencies such as U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Community impact and responses

On the ground, many residents and organizers see Swamp Sweep as more than just another enforcement push. Rachel Taber, an organizer with the New Orleans‑based advocacy group Union Migrante, said the arrival of hundreds of federal agents will shake daily life far beyond the people directly targeted for arrest.

“The same people pushing for this attack on immigrants benefit from immigrant labor and the exploitation of immigrants,” Taber said. “Who do they think is going to clean the hotels from Mardi Gras or clean up after their fancy Mardi Gras parade?”

Her comments point to the quiet role immigrants play in the local tourism economy: hotel housekeeping, restaurant kitchens, construction and festival clean‑up.

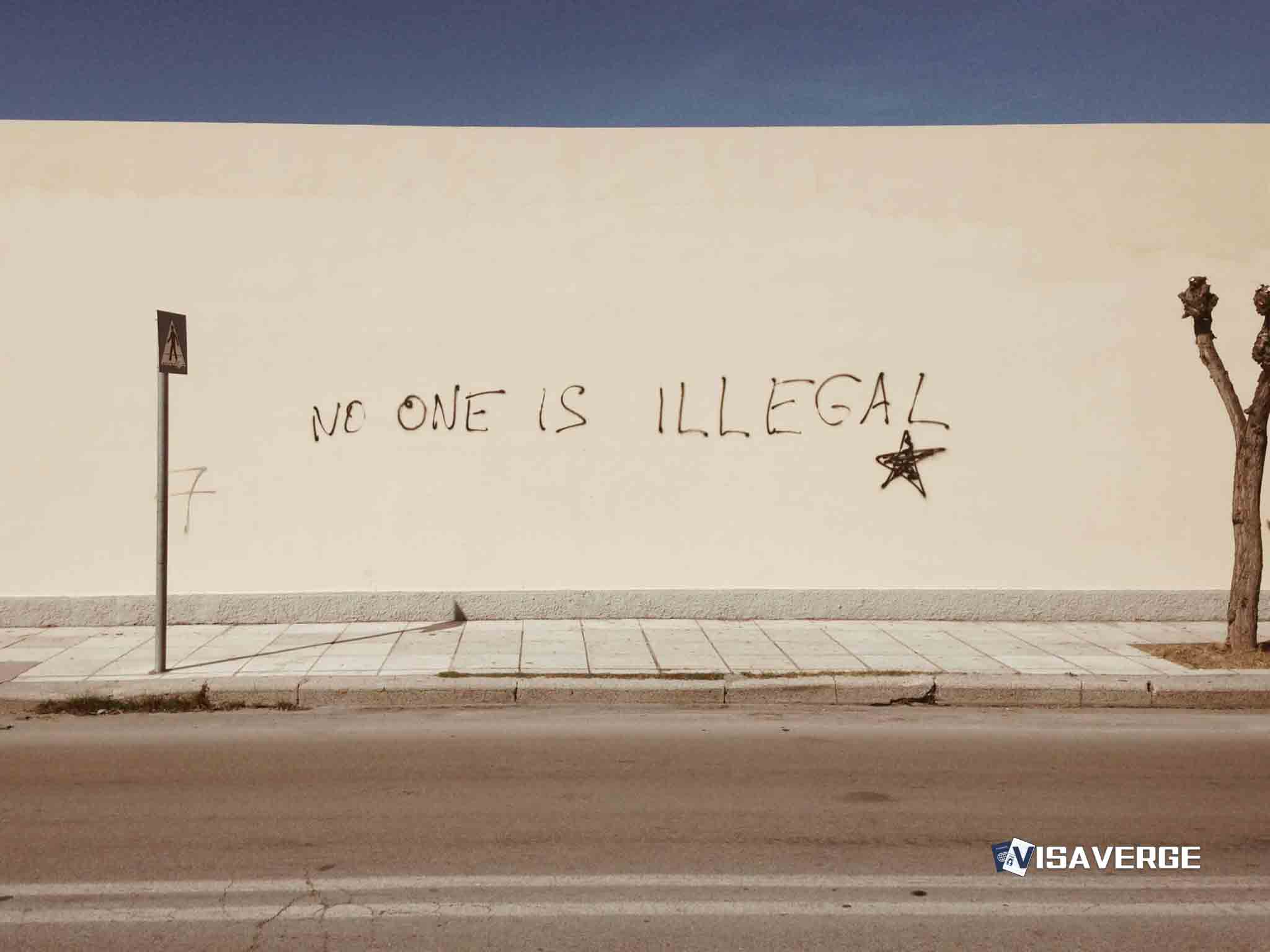

According to analysis by VisaVerge.com, operations like Swamp Sweep often become symbols in a broader fight between federal leaders pushing for tougher immigration crackdowns and city officials trying to keep trust with mixed‑status communities. In New Orleans, that clash is sharpened by the post‑Katrina story, when immigrant workers helped rebuild whole neighborhoods while facing low pay, unsafe conditions and, for many, the constant threat of removal.

Uncertainty about targets and community preparations

Federal officials have not publicly laid out how they will choose the estimated 5,000 people they plan to arrest, beyond the broad goal of targeting those without legal immigration status in southeast Louisiana and parts of Mississippi.

- For families with mixed status — including U.S.‑born children and undocumented parents — even a vague outline is enough to trigger urgent planning about child care and finances if a parent is detained.

- Lawyers and community groups are bracing for a rush of calls once the operation begins. They are preparing “know your rights” sessions and hotline support ahead of the first door knocks.

Why this matters

As Swamp Sweep nears its expected start date, New Orleans sits at the center of a growing divide:

- A federal government intent on large‑scale arrests,

- A state leadership eager to cooperate with enforcement,

- And a city that has long leaned on immigrant workers to keep its culture and economy moving.

How those forces meet on the streets in the coming weeks may shape not only the fate of thousands of residents, but also the future of immigration enforcement far beyond Louisiana.

Swamp Sweep will deploy about 250 federal agents to New Orleans in late November, launching in early December to arrest an estimated 5,000 people across southeast Louisiana and parts of Mississippi. Authorities will use FBI offices and a nearby naval base to stage operations, including storing “less lethal” munitions. The sweep heightens tensions between a state eager to cooperate with enforcement and city leaders protecting immigrant communities, prompting legal aid groups to prepare know‑your‑rights resources.