(MINNESOTA) Four Hmong Minnesotans, including a father, are scheduled for deportation to Laos this week, as of August 13, 2025, after a renewed federal push to remove Hmong residents with criminal convictions and long-standing final orders of removal. The four were arrested in June and now face flights to Laos without family, despite decades of life in Minnesota and deep ties to local schools, churches, and workplaces.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) say these removals focus on public safety and enforcement of court-ordered removals that have been final for years. Community leaders counter that many of those targeted came to the United States 🇺🇸 as children from refugee camps and have built families here. The Hmong community in Minnesota has been established for about 50 years, largely arriving after the Secret War in Laos during the Vietnam War era.

Advocates and relatives describe a wave of fear since the June arrests. Families say they often get little notice of when a plane will leave, and that calls from detention are short and stressful. Local organizers add that those facing removal may have limited or no language skills in Lao or Hmong as used in modern Laos, and few or no contacts there.

Policy Context and Enforcement Shift

Historically, Hmong refugees and their descendants were rarely deported, even when they had criminal convictions. That changed under policies that grew stricter starting in 2017.

- Under President Trump, the United States increased pressure on Laos to accept deportees.

- That pressure has continued into 2025 under President Biden.

- Analysis by VisaVerge.com indicates the federal government has kept a firm focus on enforcing old removal orders while seeking cooperation from Laos on travel documents.

Federal officials say the current approach enforces the law evenly and prioritizes people with serious convictions. DHS and ICE have recently ramped up deportations of Hmong individuals with criminal records, saying these actions reflect both public safety concerns and long-pending court decisions.

Immigration law scholars note that removing long-term residents with certain criminal convictions is legally allowed, but they also point to hard ethical questions for refugee groups tied to past U.S. actions overseas. The legacy of the Secret War in Laos and the United States’ role there are central to debates over what fairness looks like for Hmong Minnesotans who arrived as children and are now grandparents, parents, and workers in Minnesota.

For official information on arrests, detention, and removals, ICE directs the public to Enforcement and Removal Operations. Readers can find government guidance at: https://www.ice.gov/ero.

Case Details and Public Safety Rationale

One of the four facing deportation, Chia Neng Vue, has become a focal point of the controversy. Vue was convicted in 1998 of criminal sexual conduct with a child under 13, and he also had other offenses, including gang-related crimes.

- An immigration judge ordered his removal on October 31, 2003, but he remained in the country.

- He was later arrested multiple times for violent and weapons-related offenses between 2009 and 2012.

- Vue has publicly expressed remorse: “I wish I could turn back time.”

ICE points to records like these to explain its public safety priorities. The government views enforcement of final removal orders as necessary, especially for people with serious convictions.

Families and advocates counter that some individuals have lived in Minnesota for decades, completed sentences, and tried to rebuild their lives. Several in this week’s group came to the United States as children and now have U.S.-citizen children of their own. Deportation in such cases:

- Splits households

- Disrupts care for elders

- Places sudden financial and emotional strain on families

Laos has accepted deportees in recent years, but the country has limited capacity to support returnees. People removed after long stays abroad often lack housing, work connections, and cultural and language familiarity. Advocates warn that without support networks, deportees are at risk of isolation.

Local Minnesota officials and lawmakers have offered mixed views: some emphasize the pain felt by families and the community, while others back DHS and ICE on public safety and the rule of law.

Community Impact and Process Timeline

Community groups report heavy stress among Hmong families in the Twin Cities since the June arrests. Specific effects include:

- Parents racing to finish guardianship papers for kids

- Converting or consolidating bank accounts

- Arranging emergency childcare in case removal happens without warning

- Teenagers missing classes and practices due to anxiety

- Elders reliving trauma and worrying for relatives who face a country they no longer know

Typical steps in the removal process include:

- Final Order of Removal: An immigration judge orders removal after court proceedings. Some Hmong Minnesotans received these orders decades ago.

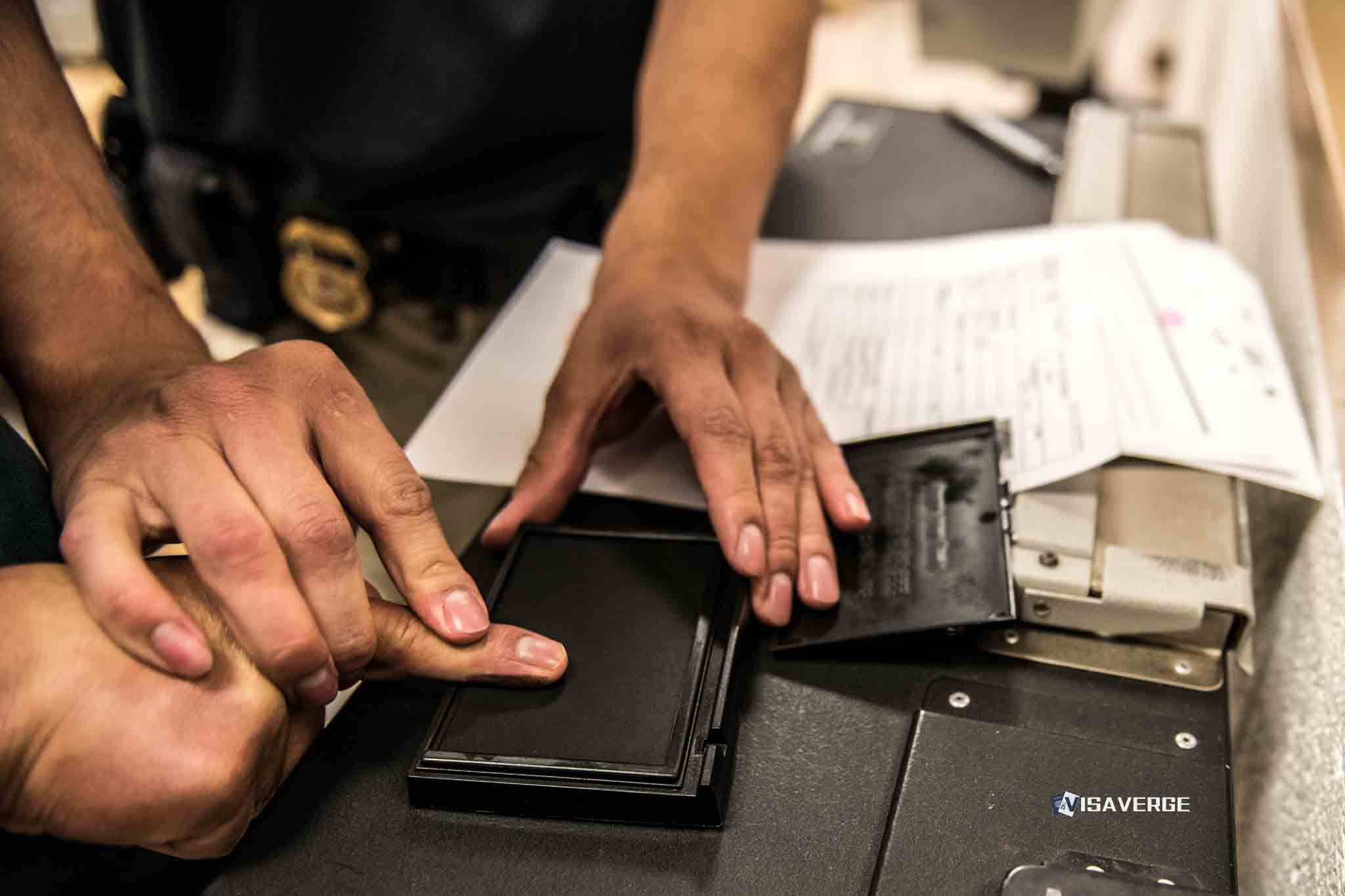

- Detention and Arrest: ICE arrests people with final orders, often during routine check-ins or targeted operations.

- Coordination with Laos: The U.S. government works with Laos to secure travel documents and clearances.

- Deportation Flight: Individuals are flown to Laos, usually without family.

- Post-Deportation: Returnees must try to reintegrate in Laos, often with limited help.

Practical effects for those removed are stark. Many left Laos as children and have spent most of their lives in Minnesota:

- They may not read or write in Lao, and some do not speak the language used in today’s Laos.

- A deportee who once worked a steady job in Saint Paul can arrive in Vientiane with no contacts, unclear legal status for work, and no money for housing.

- Families in Minnesota face sudden loss of income and care; children must cope with long separations from a parent.

Advocacy groups argue the United States has a unique responsibility to Hmong refugees because of the Secret War and the nation’s role in their displacement. They also say deportation years after people have served criminal sentences punishes families who had no part in the crimes.

Federal officials respond that immigration law requires removal for certain offenses and that final orders must be enforced to protect communities.

Analysts expect these removals to continue through 2025 and beyond, given federal priorities and Laos’ ongoing cooperation. Community groups are pressing for humanitarian relief through Congress or executive action, focusing on long-term residents who arrived as children and have deep family ties. They are also watching how Laos handles arrivals, warning that limited capacity could make reintegration harder for people removed after decades in the United States.

Help, Preparation, and Coping Steps

Families seeking help are turning to local legal aid groups and Hmong community organizations for:

- Case assessments

- Mental health support

- Family planning resources

While legal options are narrow once a final order of removal is in place, relatives can still take practical steps:

- Gather records (court, medical, school, and identity documents)

- Arrange care plans for children and elders

- Keep identification and medical records in one accessible folder

- Contact local legal aid and community organizations for emergency assistance

Advocates emphasize that even small preparations can reduce chaos if ICE gives short notice.

Important: The human stakes are high—an absent parent at class pickup, an elder without a caregiver, and children struggling to understand a sudden absence. For many Hmong families in Minnesota, this week is a harsh reminder that decades-old immigration court decisions can echo across generations.

This Article in a Nutshell

Minnesota’s Hmong community confronts sudden deportations after June arrests. Four people face removal to Laos despite decades here. Advocates stress language, family, and reintegration barriers. Officials cite final orders and public safety. Families scramble for documents, childcare, and legal help while community groups plead for humanitarian relief and policy changes.